Portsmouth Naval Shipyard

| Portsmouth Naval Shipyard | |

|---|---|

| Seavey's Island, Kittery, Maine | |

Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in 2004 | |

| Coordinates | 43°4′44″N 70°44′3″W / 43.07889°N 70.73417°W |

| Type | Shipyard |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | United States Navy |

| Open to the public | No |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1800 |

| In use | 1800–Present |

| Battles/wars | |

Portsmouth Naval Shipyard | |

| Location | Seavey Island, Kittery, Maine |

| Area | 54 acres (22 ha) |

| Architectural style | Colonial Revival, Greek Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 77000141[1] |

| Added to NRHP | November 17, 1977 |

| Garrison information | |

| Current commander | Capt. Michael Oberdorf (February 22 -present) |

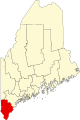

The Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, often called the Portsmouth Navy Yard, is a United States Navy shipyard on Seavey's Island in Kittery, Maine, bordering Portsmouth, New Hampshire. The naval yard lies along the southern boundary of Maine on the Piscataqua River.

Founded on June 12, 1800, PNS is U.S. Navy's oldest continuously operating shipyard. Today, most of its work concerns the overhaul, repair, and modernization of submarines.[2]

As of November 2021, the shipyard employed more than 6,500 federal employees.[3] As well, some of the work is performed by private corporations (e.g., Delphinius Engineering of Eddystone, Pennsylvania; Oceaneering International of Chesapeake, Virginia; Orbis Sibro of Mount Pleasant, South Carolina; and Q.E.D. Systems Inc. of Virginia Beach, Virginia).[4]

History

[edit]

The Portsmouth Naval Shipyard was established on June 12, 1800, during the administration of President John Adams. It sits on a cluster of conjoined islands called Seavey's Island in the Piscataqua River, whose swift tidal current prevents ice from blocking navigation to the Atlantic Ocean.[5]

The area has a long tradition of shipbuilding. Since colonial settlement, New Hampshire and Maine forests provided lumber for wooden boat construction. HMS Falkland, considered the first British warship built in the Thirteen Colonies, was commissioned here in 1696. During the Revolution, the Raleigh was built in 1776 on Badger's Island in Kittery, and became the first vessel to fly an American flag into battle. Raleigh has been depicted on the Seal of New Hampshire since 1784, even though she was captured and served in the British Navy. Other warships followed, including Ranger launched in 1777; Commanded by Captain John Paul Jones, it became the first U. S. Navy vessel to receive an official salute at sea from a foreign power. The 36-gun frigate Congress, one of the first six frigates of the United States Navy, was built at the shipyard from 1795 to 1799.

In the 1790s, Navy Secretary Benjamin Stoddert decided to build the first federal shipyard. He put it where a proven workforce had access to abundant raw materials: Fernald's Island, for which the government paid $5,500. To protect the new installation, old Fort William and Mary at the mouth of Portsmouth Harbor was rebuilt and renamed Fort Constitution.[6]

Commodore Isaac Hull was the first naval officer to command the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard; he led it from 1800 until 1802, and again in 1812 during the War of 1812. The yard's first product was the 74-gun ship of the line Washington, supervised by local master shipbuilder William Badger and launched in 1814. Barracks were built in 1820, with Marine barracks added in 1827. A hospital was established in 1834. Architect Alexander Parris was appointed chief engineer for the base. In 1838, the Franklin Shiphouse was completed: 240 feet (73 m) long, 131 feet (40 m) wide, and measuring 72 feet (22 m) from floor to center of its ridgepole. It carried 130 tons of slate on a gambrel roof. It was lengthened in 1854 to accommodate Franklin (from which it took its name); the largest wooden warship built at the yard, it required a decade to finish. The structure was considered one of the largest shiphouses in the country until it burned at 5 a.m. on March 10, 1936. Perhaps the most famous vessel ever overhauled at the yard was Constitution, also called "Old Ironsides," in 1855.[7]

On November 2, 1842, Commodore John Drake Sloat responded to a request by Navy Secretary Abel P. Upshur for information about wages and working hours at the shipyard. Sloat said the "time of work is from sunrise until sunset, except when the sun rises before 7 o'clock or sets after 6 when they commence work at 7 and quit at 6 o clock, not exceeding 10 hours labor at any season of the year." He added that wages "are always fluctuating according to the demand for mechanics".[8]

Prisoners of war from the Spanish–American War were encamped in 1898 on the grounds of the base. In 1905, construction began on the Portsmouth Naval Prison, a military prison dubbed "The Castle" because of its resemblance to a crenellated castle. It was the principal prison for the Navy and Marine Corps, as well as housing for many German U-boat crews after capture, until it closed in 1974. Also in 1905, the Portsmouth Navy Yard hosted the Treaty of Portsmouth which ended the Russo-Japanese War.[9] For arranging the peace conference, President Theodore Roosevelt won the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize. Delegates met in the General Stores Building, now the Administration Building (called Building 86). In 2005, a summer-long series of events marked the 100th anniversary of the signing of the treaty, including a visit by a Navy destroyer, a parade, and a re-enactment of the arrival of diplomats from the two nations.

During World War I, the shipyard began constructing submarines, with L-8 being the first ever built by a U. S. navy yard. Meanwhile, the base continued to overhaul and repair surface vessels. Consequently, the workforce grew to nearly 5,000 civilians. It grew to almost 25,000 civilians in World War II when over 70 submarines were constructed at the yard, with a record of 4 launched in a single day. When the war ended, the shipyard became the Navy's center for submarine design and development. In 1953, Albacore revolutionized submarine design around the world with its teardrop hull and round cross-section. It is now a museum and tourist attraction in Portsmouth. Swordfish, the first nuclear-powered submarine built at the base, was launched in 1957. The last submarine built here was Sand Lance, launched in 1969. Today the shipyard provides overhaul, refueling, and modernization work.[7]

In 1965, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara ordered the closure of 95 military bases which included the Portsmouth Naval Yard, but Portsmouth received a ten-year extension before the order to close was ultimately rescinded by President Richard Nixon in 1971.[10][11]

In the early years of submarine construction, the wood from lignum vitae tree logs was used for propeller shaft bearings. A small pond at Portsmouth, near the Naval Prison, was used to keep the lignum vitae logs submerged in water in order to prevent the wood from cracking. Although the use of wood was discontinued as construction techniques improved, many of the logs were still present during the construction of USS Jack between 1963 and 1967.[citation needed]

The 2005 Base Realignment and Closure Commission placed the yard on a list for base closures, effective by 2008. Employees organized the Save Our Shipyard campaign to influence the committee to reverse its decision. On 24 August 2005, the base was taken off the list and continues operating under its motto, "From Sails to Atoms."[5]

The shipyard earned the Meritorious Unit Commendation in 2005. The MUC recognized the shipyard for meritorious service from September 11, 2001, to August 30, 2004. Portsmouth Naval Shipyard accomplishments achieved during that period included completion of six major submarine availabilities early, exceeding Net Operation Results financial goals, reducing injuries by more than 50 percent, and exceeding the Secretary of Defense's Fiscal Year 2006 Stretch Goal for lost workday compensation rates two years early.

In addition to the Navy presence, the United States Army New England Recruiting Battalion moved to PNSY in June 2010 from the closed Naval Air Station Brunswick. The United States Coast Guard uses the Portsmouth Navy Yard as the home port for the medium-endurance cutters Reliance, Tahoma, and Campbell.[12]

PNS is undergoing substantial construction and infrastructure upgrades. In fiscal 2020, Navy contracts were issued to renovate the communications building,[13] build a super flood basin and extend crane rails in Dry Dock 1,[14][15] upgrade crane rails in Dry Dock 2,[16] renovate Building 2,[17] and implement sundry waterfront projects.[18]

The summer of 2021 saw an uptick in construction contracts issued for Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, including purchase and installation of three 12,000-gallon-per-minute dewatering pumps for the Dry Dock 1 extension,[19] ongoing construction of the Dry Dock 2 complex,[20] commencement of construction on the Virginia-class submarine waterfront support facility (Building 178),[21] and a $1.73 billion contract for building a dry dock for maintenance and upgrade of Virginia-class submarines.[22]

Superfund site

[edit]In 1994, the shipyard was placed on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency National Priorities List (NPL) for environmental investigations/restorations under CERCLA (Superfund) after an investigation found groundwater, soil and sediment contamination with polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAHs), metals and benzene. In 2024, the EPA removed the shipyard from the National Priorities List of contaminated Superfund. The removal followed 30 years of extensive remediation at the 278-acre shipyard, including the removal of contaminated soil, sediment and other hazardous materials.[23]

Boundary dispute

[edit]New Hampshire laid claim to the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard until the U.S. Supreme Court dismissed the case in 2001, asserting judicial estoppel.[24] Had it been found to belong to New Hampshire, base employees (and their spouses regardless of whether they themselves worked in Maine) from that state would no longer be required to pay Maine income tax. Despite the court's ruling, New Hampshire's 2006 Session House Joint Resolution 1 reaffirmed its sovereignty assertion over Seavey's Island[25] and the base.

Safety concerns

[edit]A CDC / NIOSH study released in 2005 examined the cases of 115 employees at the shipyard who had died of leukemia between 1952 and 1992. The results suggested that leukemia mortality risk increased with increasing cumulative occupational ionizing radiation dose among PNS workers.[26]

Dry docks and slipways

[edit]| Dock No. | Material of which dock is constructed | Length | Width | Depth | Date Completed | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Concrete | 435 feet 3 inches (132.66 m) | 104 feet (32 m) | 25 feet (7.6 m) | 1942 | [27] |

| 2 | Concrete and granite | 686 feet 5 inches (209.22 m) | 129 feet (39 m) | 30 feet 4 inches (9.25 m) | 1905 | |

| 3 | Concrete | 486 feet (148 m) | 71 feet (22 m) | 37 feet (11 m) | 1962 |

| January 1, 1946 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Shipbuilding ways | Width | Length | Source |

| 1 | 48 feet (15 m) | 369 feet (112 m) | [28] |

| 2 | 46 feet 6 inches (14.17 m) | 369 feet (112 m) | |

| 3 | 46 feet 6 inches (14.17 m) | 369 feet (112 m) | |

| 4 | 52 feet (16 m) | 369 feet (112 m) | |

| 5 | ..... | 324 feet (99 m) | |

Notable ships built at shipyard predecessors

[edit]- 1690 — HMS Falkland - (50-gun fourth-rate)[29]

- 1696 — HMS Bedford Galley - (32-gun fifth-rate)[29]

- 1749 — HMS America - (60-gun fourth-rate)[29]

- 1776 — Raleigh - (32-gun frigate)[29]

- 1777 — Ranger - (18-gun sloop-of-war)[29]

- 1782 — America - (74-gun ship of the line)[29]

- 1791 — Scammel - (revenue cutter)[29]

- 1797 — Crescent - (36-gun frigate)[29]

- 1798 — Portsmouth - (24-gun sloop-of-war)[29]

- 1799 — Congress - (38-gun frigate)[29]

Notable ships built at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard

[edit]

- 1814 — Washington - (74-gun ship of the line)[29]

- 1820 — Porpoise - (11-gun schooner)[29]

- 1828 — Concord - (24-gun sloop-of-war)[29]

- 1839 — Preble - (20-gun sloop-of-war)[29]

- 1841 — Congress - (50-gun frigate)[29]

- 1842 — Saratoga - (24-gun sloop-of-war)[29]

- 1843 — Portsmouth - (24-gun sloop-of-war)[29]

- 1848 — Saranac - (steam sloop)[29]

- 1855 — Santee - (44-gun frigate)[29]

- 1855 — LV-1 - Lightship Nantucket[29]

- 1859 — Mohican - (steam sloop)[29]

- 1861 — Kearsarge - (steam sloop)[29]

- 1861 — Ossipee - (steam sloop)[29]

- 1861 — Sebago - (side-wheel steam gunboat)[29]

- 1861 — Mahaska - (side-wheel steam gunboat)[29]

- 1862 — Sonoma - (side-wheel steam gunboat)[29]

- 1862 — Conemaugh - (side-wheel steam gunboat)[29]

- 1862 — Sassacus - (side-wheel steam gunboat)[29]

- 1862 — Sacramento - (steam sloop)[29]

- 1863 — Nipsic - (steam gunboat)[29]

- 1863 — Shawmut - (steam gunboat)[29]

- 1863 — Agamenticus - (Miantonomoh-class monitor)[29]

- 1864 — New Hampshire - (74-gun ship of the line)[29]

- 1864 — Contoocook - (steam sloop)[29]

- 1864 — Franklin - (steam frigate)[29]

- 1864 — Pawtuxet - (side-wheel steam gunboat)[31]

- 1864 — Blue Light - (tugboat)[29]

- 1864 — Port Fire - (tugboat)[29]

- 1865 — Resaca - (steam gunboat)[29]

- 1866 — Piscataqua - (steam frigate)[29]

- 1867 — Minnetonka - (steam frigate)[29]

- 1868 — Benicia - (steam sloop)[29]

- 1874 — Enterprise - (steam sloop)[29]

- 1905 — Boxer - (training brigantine)[29]

- 1908 — Patapsco - (tugboat)[29]

- 1917 — L-8 - (United States L-class submarine)[29]

- 1918 — O-1 - (United States O-class submarine)[29]

- 1918 — S-3 - (United States S-class submarine)[29]

- 1919 — S-4 - (United States S-class submarine)[29]

- 1919 — S-5 - (United States S-class submarine)[29]

- 1919 — S-6 - (United States S-class submarine)[29]

- 1920 — S-7 - (United States S-class submarine)[29]

- 1920 — S-8 - (United States S-class submarine)[29]

- 1920 — S-9 - (United States S-class submarine)[29]

- 1920 — S-10 - (United States S-class submarine)[29]

- 1921 — S-11 - (United States S-class submarine)[29]

- 1921 — S-12 - (United States S-class submarine)[29]

- 1921 — S-13 - (United States S-class submarine)[29]

- 1924 — Barracuda - (diesel submarine)[29]

- 1924 — Bass - (diesel submarine)[29]

- 1924 — Bonita - (diesel submarine)[29]

- 1928 — Argonaut - (diesel submarine minelayer)[29] 3 World War II Pacific patrols[32]

- 1929 — Narwhal - (diesel submarine cruiser)[29] sank 6 ships in 15 World War II Pacific patrols[32]

- 1932 — Dolphin - (diesel submarine)[29] 3 World War II Pacific patrols[32]

- 1933 — Cachalot - (diesel submarine)[29] 3 World War II Pacific patrols[32]

Souvenir of the launch of the USS Cacholot - 1934 — Hudson - (USCG Calumet-class harbor tug)[33]

- 4 of 10 United States Porpoise-class submarines [29][32]

- 1935 — Porpoise - sank 2 ships in 6 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1935 — Pike - sank 1 ship in 8 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1936 — Plunger - sank 13 ships in 12 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1936 — Pollack - sank 11 ships in 11 World War II Pacific patrols

- 2 of 6 Salmon-class submarines

- 1937 — Snapper - sank 4 ships in 11 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1937 — Stingray - sank 2 ships in 16 World War II Pacific patrols

- 4 of 10 Sargo-class submarines [29][32]

- 1938 — Sculpin - sank 3 ships in 9 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1939 — Sailfish - sank 7 ships in 12 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1939 — Searaven - sank 3 ships in 13 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1939 — Seawolf - sank 18 ships in 15 World War II Pacific patrols

- 4 of 12 Tambor-class submarines [29][32]

- 1940 — Triton - sank 11 ships in 6 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1940 — Trout - sank 12 ships in 11 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1940 — Grayling - sank 2 ships in 8 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1940 — Grenadier - sank 1 ship in 6 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1 of 2 Mackerel-class submarines [32]

- 1941 — Marlin

- 14 of 77 Gato-class submarines [29][32]

- 1941 — Drum - sank 12 ships in 13 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1941 — Flying Fish - sank 15 ships in 12 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1941 — Finback - sank 11 ships in 12 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1941 — Haddock - sank 8 ships in 13 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1941 — Halibut - sank 12 ships in 10 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1942 — Herring - sank 6 ships in 5 Atlantic and 3 Pacific World War II patrols

- 1942 — Kingfish - sank 14 ships in 12 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1942 — Shad - sank 3 ships in 11 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1942 — Runner - 3 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1942 — Sawfish - sank 6 ships in 10 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1942 — Scamp - sank 5 ships in 8 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1942 — Scorpion - sank 4 ships in 4 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1942 — Snook - sank 17 ships in 9 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1942 — Steelhead - sank 4 ships in 7 World War II Pacific patrols

- 42 of 120 Balao-class submarines [29][34][32]

- 1942 — Balao - sank 6 ships in 10 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1942 — Billfish - sank 3 ships in 8 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1942 — Bowfin - sank 16 ships in 9 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1942 — Cabrilla - sank 7 ships in 8 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1942 — Capelin - sank 1 ship in 1 World War II Pacific patrol

- 1942 — Cisco - 1 World War II Pacific patrol

- 1943 — Crevalle - sank 8 ships in 7 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1943 — Apogon - sank 3 ships in 8 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1943 — Aspro - sank 6 ships in 7 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1943 — Batfish - sank 6 ships in 7 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1943 — Archerfish - sank 2 ships in 7 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1943 — Burrfish - sank 1 ship in 6 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1943 — Sand Lance - sank 10 ships in 5 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1943 — Picuda - sank 13 ships in 6 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1943 — Pampanito - sank 5 ships in 6 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1943 — Parche - sank 8 ships in 6 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1943 — Bang - sank 8 ships in 6 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1943 — Pilotfish - 6 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1943 — Pintado - sank 8 ships in 6 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1943 — Pipefish - sank 2 ships in 6 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1943 — Piranha - sank 2 ships in 5 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1943 — Plaice - sank 4 ships in 6 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1943 — Pomfret - sank 4 ships in 6 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1943 — Sterlet - sank 4 ships in 5 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1943 — Queenfish - sank 8 ships in 5 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Razorback - 5 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Redfish - sank 5 ships in 2 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Ronquil - sank 2 ships in 5 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Scabbardfish - 5 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Segundo - sank 2 ships in 5 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Sea Cat - 2 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Sea Devil - sank 5 ships in 5 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Sea Dog - sank 9 ships in 4 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Sea Fox - [35] 4 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Atule - sank 6 ships in 4 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Spikefish - sank 1 ship in 4 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Sea Owl - sank 2 ships in 3 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Sea Poacher - 4 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Sea Robin - sank 6 ships in 3 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Sennet - sank 7 ships in 4 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Piper - 3 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Threadfin - sank 3 ships in 3 World War II Pacific patrols

- 24 of 29 Tench-class submarines [34][32]

- 1944 — Tench - sank 4 ships in 3 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Thornback - 1 World War II Pacific patrol

- 1944 — Tigrone - 2 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Tirante - sank 8 ships in 2 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Trutta - 2 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Toro - 2 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Torsk - sank 3 ships in 2 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Quillback - 1 World War II Pacific patrol

- 1944 — Argonaut - sank 1 ship in 1 World War II Pacific patrol

- 1944 — Runner - sank 1 ship in 2 World War II Pacific patrols

- 1944 — Conger

- 1944 — Cutlass - 1 World War II Pacific patrol

- 1944 — Diablo - 1 World War II Pacific patrol

- 1944 — Medregal

- 1945 — Requin

- 1945 — Irex

- 1945 — Sea Leopard

- 1945 — Odax

- 1945 — Sirago

- 1945 — Pomodon

- 1945 — Remora

- 1945 — Sarda

- 1945 — Spinax

- 1945 — Volador

- 1951 — Tang - (diesel submarine)[34]

- 1951 — Wahoo - (diesel submarine)[34]

- 1951 — Gudgeon - (diesel submarine)[34]

- 1953 — Albacore - (experimental diesel submarine)[34]

- 1955 — Sailfish - (RADAR picket submarine)[34]

- 1956 — Salmon - (RADAR picket submarine)[34]

- 1958 — Growler - (guided missile diesel submarine)[34]

- 1958 — Swordfish - (nuclear submarine)[34]

- 1958 — Barbel - (fast diesel submarine)[34]

- 1958 — Seadragon - (nuclear submarine)[34]

- 1960 — Thresher - (nuclear fast attack submarine)[34]

- 1960 — Abraham Lincoln - (nuclear ballistic missile submarine)[34]

- 1963 — Jack - (nuclear fast attack submarine)[34]

- 1961 — Tinosa - (nuclear fast attack submarine)[34]

- 1963 — John Adams - (nuclear ballistic missile submarine)[34]

- 1964 — Nathanael Greene - (nuclear ballistic missile submarine)[34]

- 1967 — Grayling - (nuclear fast attack submarine)[36]

- 1968 — Dolphin - (experimental diesel submarine)[37]

- 1969 — Sand Lance - (nuclear fast attack submarine)[36]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ Home - Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. Navsea.navy.mil (1939-05-23). Retrieved on 2014-05-24.

- ^ "Nearly 2,000 Portsmouth Naval Shipyard workers are not vaccinated as federal mandate deadline arrives". Maine Public. November 22, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2022.

- ^ "Contracts". U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ a b "History of the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2016.

- ^ A. J. Coolidge & J. B. Mansfield, A History and Description of New England; Boston, Massachusetts 1859

- ^ a b Brief History of the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard

- ^ Sloat to A.P.Upshur, 2 November 1842,pp.1-2, Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy From Captains ("Captains Letters") 1805-1861, Volume 295, 1 Nov 1842 - 30 Nov 1842, Letter Number 21, RG 260, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

- ^ Treaty of Portsmouth -- U.S. Department of State

- ^ "Historic Portsmouth: Shipyard closure 'irrevocable' in 1964".

- ^ "Case not closed yet: Yard has fought off closure before".

- ^ "USCGC RELIANCE". U.S. Coast Guard. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- ^ "Contracts for September 21, 2020". U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ "Contracts for November 21, 2019". U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ "Contracts for December 27, 2019". U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ "Contracts for June 24, 2020". U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ "Contracts for November 20, 2019". U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ "Contracts for September 1, 2020". U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ "Contracts for July 9, 2021". U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ "Contracts for August 30, 2021". U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ "Contracts for August 5, 2021". U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ "Contracts for August 13, 2021". U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ Bouchard, Kelly (February 17, 2024). "Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery no longer listed as contaminated Superfund site". Portland Press Herald. Retrieved March 5, 2024.

- ^ Yard in Maine, Portsmouth Herald, 30 May 2001. "Portsmouth Herald Local News: Yard in Maine". Archived from the original on March 27, 2005. Retrieved November 15, 2006.

- ^ hjr 0001

- ^ "A Nested Case-Control Study of Leukemia and Ionizing Radiation at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard (2005-104)". CDC - NIOSH Publications and Products -. June 6, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- ^ "Drydocking Facilities Characteristics" (PDF).

- ^ Gardiner Fassett, Frederick (1948). The Shipbuilding Business in the United States of America. Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers. p. 177.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq Alden 1964 p. 92

- ^ "Launching of the USS Washington". Historic New England. Retrieved February 20, 2018.

- ^ "Pawtuxet". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved September 6, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Blair(1975)pp.875-957

- ^ Fahey 1941 p. 43

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Alden 1964 p. 93

- ^ Alden 1964 p. 93

- ^ a b Blackman 1970-71 p. 466

- ^ Blackman 1970-71 p. 476

Sources

[edit]- Portsmouth Naval Shipyard Museum & Research Library (Building 31)

- Alden, John, CDR USN (November 1964). Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. United States Naval Institute Proceedings.

{{cite conference}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Blackman, Raymond V.B. (1970–71). Jane's Fighting Ships. Jane's Yearbooks.

- Blair, Clay Jr. (1975). Silent Victory volume 2. J.B. Lippincott.

- Fahey, James C. (1941). The Ships and Aircraft of the U.S. Fleet, Two-Ocean Fleet Edition. Ships and Aircraft.

- Switzer, David C. (November 1964). Down-East Ships of the Union Navy. United States Naval Institute Proceedings.

- Watterson, Rodney K. (2011). 32 in '44: Building the Portsmouth Submarine Fleet in World War II. Naval Institute Press. p. 208. ISBN 978-1591149538.

External links

[edit]- United States Navy shipyards

- Shipyards of Maine

- Military installations in Maine

- Military Superfund sites

- Economic history of Maine

- Military history of Maine

- History of New Hampshire

- Buildings and structures in Kittery, Maine

- Superfund sites in Maine

- Historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places in Maine

- 1800 establishments in the United States

- National Register of Historic Places in York County, Maine

- Shipyards on the National Register of Historic Places

- Shipyards building World War II warships

- Former submarine builders