Ghoulardi

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2019) |

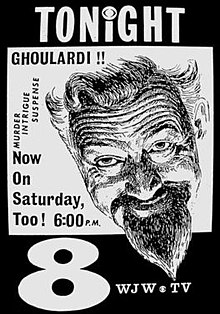

Ghoulardi was a fictional character created and portrayed by voice announcer, actor and disc jockey Ernie Anderson as the horror host of Shock Theater at WJW-TV, Channel 8 (a.k.a. "TV-8") the CBS Affiliate station in Cleveland, Ohio, from January 13, 1963, through December 16, 1966.[1] Shock Theater featured grade-"B" science fiction films and horror films, aired in a Friday late-night time slot. At the peak of Ghoulardi's popularity, the character also hosted the Saturday afternoon Masterpiece Theater, and the weekday children's program Laurel, Ghoulardi and Hardy.

Background

[edit]Anderson, a big band and jazz and classic film enthusiast, was born in Boston on November 12, 1923, grew up in Lynn, Massachusetts, and served in the U.S. Navy during World War II. After the war, he worked as a disc jockey in several markets, including Cleveland, Ohio, before switching to television. He joined the staff of WJW TV-8 in 1961 as an announcer and movie program host, but his original hosted movie program was soon cancelled, although he remained under contract to the station as a booth announcer. Anderson then agreed to host Shock Theater in character for an additional $65 per week on top of his regular salary.[2]

History

[edit]Character

[edit]Late-night horror hosts in other broadcast markets typically portrayed themselves as mad scientists, vampires, or other horror film-themed stock characters. In contrast to this, Anderson's irreverent and influential host character was a hipster. Ghoulardi's costume was a long lab coat covered with "slogan" buttons, horn-rimmed sunglasses with a missing lens, a fake Van Dyke beard and moustache, and various messy, awkwardly-perched wigs. Anderson agreed from the beginning to wear the Ghoulardi disguise on camera so that the notoriety of the character would not interfere with his conventional outside voiceover work. Anderson's crew shone a key light on his face at an unusual angle to create a spooky effect, and they shot his face close up (or extremely close up), which they often broadcast through an undulating oval.

Ghoulardi's stage name and certain aspects of the character's appearance were devised by Cleveland restaurateur and amateur makeup artist Ralph Gulko, who was making a pun of the word "ghoul," and his own similar last name, suffixed with a generic "ethnic" ending. The station created a "write in" contest for fans after Gulko devised the name, and station management awarded prizes to several contestants who sent in ideas for names similar to the one they had already chosen.

Anderson used friends and members of the TV-8 station crew as supporting cast, including engineer "Big Chuck" Schodowski, film editor Bob Soinski, weatherman Bob "Hoolihan" Wells, and occasionally Tim Conway, a former TV-8 colleague who had gone on to stardom as "Ensign Parker" in the ABC sitcom McHale's Navy. Anderson was later assisted by teenage intern Ron Sweed, who had boarded a bus to try to meet his idol at a live appearance at Euclid Beach Park, clad in a gorilla suit. Anderson invited Sweed onstage; to the crowd’s delight, Sweed stumbled offstage back into the audience when Anderson whacked him on the back. This, plus some unannounced gorilla-suited visits to the studio, sealed his place as Anderson’s intern.

During breaks in the movies, Ghoulardi addressed the TV-8 camera in a part-Beat, part-ethnic accented commentary, peppered with catchphrases: "Hey, group!", "Stay sick, knif" ("fink" backwards), "Cool it", "Turn blue", "Would you believe...?" and "ova-dey" (a regional pronunciation of "over there"). Anderson improvised because of his difficulty memorizing lines. He played novelty and offbeat or instrumental rock and roll tunes, plus jazz and rhythm and blues songs under his live performance, frequently "The Desert Rat", flip side of "Boss Guitar" by Duane Eddy. He frequently played The Rivingtons' "Papa-Oom-Mow-Mow" over a clip of a toothless old man gurning.

Ghoulardi frequently mocked the poor quality films he was hosting on TV-8: "If you want to watch a movie, don't watch this one," or "This movie is so bad, you should just go to bed." He had his crew comically insert random stock footage or his own image at climactic moments. In a scene involving a chase, for example, they integrated Ghoulardi into the film as if he was being pursued, or interacting with other characters. When airing Attack of the 50 Foot Woman, Ghoulardi leaned his hand up on the wall of a cave in one scene. Schodowski wrote that Ghoulardi usually adapted well to the changing scenes, as Anderson could only view a monitor with a reversed image of the broadcast and his "drop-ins" were live. One time the scene in the film changed before Anderson noticed, and he reacted with a "Whooo!" and quickly removed his hand when he realized that Ghoulardi was cupping the breast of the giant woman (Allison Hayes) live onscreen.

Popularity

[edit]At his show's peak, Ghoulardi scored 70 percent of the late-night audience.[citation needed] Fans sent up to 1,000 pieces of mail a day.[citation needed] The Cleveland Police Department attributed a 35 percent decline in juvenile crime to the Friday night show. Anderson quipped, "Nobody likes to steal the car in a blizzard."[citation needed]

Ghoulardi's regional popularity grew so large that he was engaged for a second television show, Laurel, Ghoulardi, & Hardy. Featuring classic Laurel & Hardy comedy films, the weekday afternoon show premiered in July 1963.[3]

TV-8, then owned by Storer Broadcasting, further capitalized on Ghoulardi's wide audience with a comprehensive merchandising program, giving Anderson a percentage as Storer owned the "Ghoulardi" name. Anderson also negotiated agreements with Manners Big Boy Restaurants for use of his image, though Anderson refused to eat fast food ("Don't eat that — it's garbage," he advised Sweed). He earned about $65,000 a year at the peak of his popularity as Ghoulardi.

Charitable work

[edit]Anderson organized the "Ghoulardi All-Stars" softball, football and basketball teams, which played as many as 100 charity contests a year, attracting thousands of fans. Tim Conway recalls that in softball games they "actually filled Cleveland Stadium." They donated all receipts to charity after recouping expenses such as uniforms and coach transportation. Bob Wells estimated that the Ghoulardi All-Stars raised about $250,000. Anderson staffed the teams with TV-8 personalities, crew, their family members and, occasionally, when he only remembered the game he had booked when he saw the team bus parked in front of the station, anyone else he could find. TV-8 sent a cameraman to cover games, and Ghoulardi improvised humorous narratives to these highlight films, which saved him show preparation.

At one point, TV-8's program director interfered by making the excuse that the station could not afford the overtime for the cameraman. Ghoulardi explained that the lack of highlight films was hurting attendance, which disrupted their charitable work. Ghoulardi had a camera shoot a card printed with the program director's home phone number, which he televised, and asked the broadcast audience to complain. The program director relented after being forced to change his number.

Controversy

[edit]Ghoulardi often made fun of targets he considered "unhip", including bandleader Lawrence Welk, Mayor of Cleveland Ralph Locher, and Cleveland local television personalities such as singer/local talk show host Mike Douglas, children's hosts Barnaby and Captain Penny, local newscaster Bill Jorgensen, and news analyst and commentator Dorothy Fuldheim (whom he called "Dorothy Baby"). According to Anderson, Mike Douglas refused to book Anderson as a guest on his talk show The Mike Douglas Show after it began nationwide broadcasting, and also refused to speak to Anderson for years (though Douglas denied any animosity).

Ghoulardi also lampooned the bedroom communities of Parma, Ohio, which he often called "Par-ma?!" or "Amrap" (Parma backwards), and Oxnard, California, saying "Remember...Oxnard!" and featuring a raven named "Oxnard" on his show. Ghoulardi unmercifully jeered Parma for what he considered its conservative, ethnic, working-class "white socks" sensibility, making fun of such local customs as listening to polka music and decorating front lawns with pink plastic flamingoes and yard globe ornaments. The Ghoulardi program even aired a series of taped skits called "Parma Place", featuring Anderson and Schodowski playing stereotypical ethnic Parma residents in a parody of the then-popular prime time soap opera Peyton Place. While the "Parma Place" skits were well received by the public, the mayor of Parma and other local politicians complained to station management, especially after learning that the spectators at a Parma vs. Parma Heights high school basketball game had thrown white socks onto the court. Under pressure, the station forced Anderson to discontinue the "Parma Place" skits.

Anderson openly battled TV-8 management. Schodowski recalled that "station management lived in daily fear as to what he might say or do on the air, because he was live." In spite of his solid ratings and profitability, they worried that Ghoulardi was testing too many television boundaries too quickly, and tried to rein in the character. Anderson responded by, among other things, detonating plastic action figures and plastic model cars sent in by viewers with firecrackers and small explosives on air, once nearly setting the studio on fire. As Anderson was already under contract with TV-8 as a booth announcer when Ghoulardi first aired, Storer Broadcasting had to pay him, so Anderson cared little about whom he offended. Anderson was also reprimanded for riding his motorcycle through the program director's office, and for staying at a close, late-running Friday night Cleveland Browns game long after his show's 11:30 p.m. start time.

Retirement of the "Ghoulardi" character

[edit]Induced by greater career promise and show business contacts of Tim Conway, who had already left town and found success as an actor in Los Angeles, Anderson abruptly retired Ghoulardi and stopped performing live in September 1966. Anderson never pinpointed the reason, and his decision to leave was a surprise to close associates such as Schodowski. His biographers attribute Ghoulardi's retirement to Anderson's being weary of portraying the Ghoulardi character into his forties, disruption caused by his ongoing divorce, and clashes with station management.

During 1966, Anderson moved to Los Angeles to pursue an acting career. For a few months, he periodically returned to Cleveland to tape additional Ghoulardi shows, the last of which aired in December 1966. In late December 1966, TV-8's Bob "Hoolihan" Wells and "Big Chuck" Schodowski took over Ghoulardi’s Friday night movie time slot as co-hosts of The Hoolihan and Big Chuck Show. Schodowski continued to host the show until July 2007, replacing the departing Wells with new co-host "Li'l John" Rinaldi in 1979.

Anderson subsequently made a successful career in prestigious voice-over work, most prominently as the main voice of the ABC TV network during the 1970s and 1980s. He reprised his Ghoulardi character only once, in 1991 on an episode of Joe Bob's Drive-In Theater hosted by Joe Bob Briggs. Anderson died of cancer on February 6, 1997.

Influence and legacy

[edit]In the mid-1960s, Ghoulardi's irreverence overtook the rarefied Severance Hall, where an Italian Cleveland Orchestra guest conductor introduced himself and said that he was from Parma (in northern Italy). According to Tim Conway, misunderstanding members of the audience burst out singing Ghoulardi's polka theme.

In 1971, Anderson's former intern Ron Sweed first appeared on WKBF-TV (UHF channel 61 in Cleveland) as "The Ghoul," borrowing the "Ghoulardi" character traits and costume with Anderson’s blessing, but with a name change because Storer Broadcasting still owned the "Ghoulardi" name. The Ghoul Show went on to air for many years in Cleveland, Detroit, and limited national syndication.

Cleveland native Drew Carey has paid tribute to Ghoulardi in his television sitcom The Drew Carey Show, where his character can often be seen wearing a Ghoulardi T-shirt. Season 2, Episode 17 of the show ("See Drew Run") was dedicated to the memory of Ernie Anderson, who died shortly before the episode first aired. In his endorsement of the biography, Ghoulardi: Inside Cleveland TV’s Wildest Ride, Carey is quoted as saying, "Absolutely, big time, Ghoulardi was an influence on me."

Ghoulardi's influence ultimately inspired the music and performance styles of a number of rock and punk bands from Cleveland and Akron, Ohio. The self-proclaimed "psychobilly" band, The Cramps, named their 1990 album Stay Sick! and dedicated their 1997 album, Big Beat From Badsville, to Ghoulardi's memory. David Thomas, of art rock band Pere Ubu, said that the Cramps were "so thoroughly co-optive of the Ghoulardi persona that when they first appeared in the 1970s, Clevelanders of the generation were fairly dismissive." Thomas credits Ghoulardi for influencing the "otherness" of the Cleveland/Akron bands of the mid-1970s and early-1980s, including the Electric Eels, The Mirrors, the Cramps, and Thomas's own groups, Pere Ubu and Rocket From The Tombs, declaring, "We were the Ghoulardi kids." Members of Devo and The Dead Boys have also cited Ghoulardi as a strong influence.[4][5] Pretenders founder Chrissie Hynde, an Akron native, referred to Ghoulardi as a local "guru": "He had his own language and we idolized him, the Beat version of a ghoul."[6]

In 2002, Cleveland-area indie band Uptown Sinclair featured a Ghoulardi-derived basketball referee in the slapstick music video for their song "Girlfriend." In 2003, as a tribute, jazz organist Jimmy McGriff wrote, recorded and released his song "Turn Blue." The Akron-based band the Black Keys also paid homage to a Ghoulardi catchphrase with their 2014 album Turn Blue.

Ghoulardi's influence also extended to film. Anderson's son, film director Paul Thomas Anderson, named his production entity "The Ghoulardi Film Company" and has stated that the climactic fireworks scene in his film Boogie Nights was inspired by Ghoulardi's use of fireworks.[7] Director Jim Jarmusch, who grew up in the Cleveland area and watched Ghoulardi as a child, has also said that he was influenced by the character's anti-authoritarian attitude and selection of "weird" music.[4] In Denmark, editor Jack J named his movie fanzine Stay Sick! (1999-) after having read an article on Ghoulardi by Michael J. Weldon in an early issue of Weldon's Psychotronic Video magazine.

Over 50 years after Ghoulardi signed off, many Clevelanders still associate polka music, white socks, and pink plastic flamingo and yard globe lawn ornaments with Parma, Ohio.

References

[edit]- ^ Watson, Elena M. (2000). Television Horror Movie Hosts: 68 Vampires, Mad Scientists and Other Denizens of the Late Night Airwaves Examined and Interviewed. Jefferson, North Carolina, United States: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-0940-1.

- ^ Hoffman, Phil, producer/director (2009). Turn Blue: The Short Life of Ghoulardi (Motion picture documentary). Roc Doc Productions/ Western Reserve Public Media. Archived from the original on 2021-12-12. Retrieved 2015-10-04.

- ^ "Cleveland's Cool Ghoul". The Sandusky Register. Sandusky, OH. July 5, 1963. Retrieved June 25, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Petkovic, John (2013-01-12). "Cleveland's Ghoulardi Went On the Air 50 Years Ago and Cast His Spell Over the City". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved 2015-10-03.

- ^ Urycki, Mark (2013-12-21). "50 Years Later, TV's Ghoulardi Lives — In Punk Rock". NPR. Retrieved 2015-10-03.

- ^ Chrissie Hynde (2015). Reckless: My Life as a Pretender. Doubleday, New York. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0-385-54061-2.

- ^ Konow, David (2014-12-11). "How Paul Thomas Anderson Was Influenced By His Irreverent Dad". Esquire. United States: Hearst Corporation. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-03.

Further reading

[edit]- Feran, Tom, and R. D. Heldenfels (1997). Ghoulardi: Inside Cleveland TV's Wildest Ride. Cleveland, OH: Gray & Company Publishers. ISBN 978-1-886228-18-4

- Schodowski, Chuck (2008). Big Chuck: My Favorite Stories from 47 Years on Cleveland TV. Cleveland, OH: Gray & Company, Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59851-052-2

- Feran, Tom; R.D. Heldenfels (1997). Ghoulardi: Inside Cleveland TV's Wildest Ride. Cleveland: Gray and Company. ISBN 1-886228-18-3.

- Thomas, David (2005). "Ghoulardi: Lessons in Mayhem from the First Age of Punk". 2005 Pop Conference (PDF). Working Draft. 2005 Pop Conference, Experience Music Project. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-05-25.

- "The Big Chuck and Li'l John Show," WJW-TV, broadcast ca., 1998, viewable at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e52cXCrmauc (as of 12/19/06).