Camorra

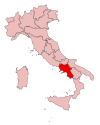

| Founding location | Campania, Italy |

|---|---|

| Years active | Since the 18th century |

| Territory | Territories with established coordination structures with significant territorial control are in Campania, in particular in the provinces of Naples, Caserta and Salerno. The Camorra has secondary ramifications in other Italian regions as well as in other countries with varying degrees of presence. |

| Ethnicity | Campanians |

| Membership | 10,000[1][2][3] full members, unknown number of associates |

The Camorra (Italian: [kaˈmɔrra]; Neapolitan: [kaˈmorrə]) is an Italian Mafia-type[4] criminal organization and criminal society originating in the region of Campania. It is one of the oldest and largest criminal organizations in Italy, dating to the 18th century. The Camorra's organizational structure is divided into individual groups called "clans". Every capo or "boss" is the head of a clan, in which there may be tens or hundreds of affiliates, depending on the clan's power and structure. The Camorra's main businesses are drug trafficking, racketeering, counterfeiting, and money laundering. It is also not unusual for Camorra clans to infiltrate the politics of their respective areas.

Since the early 1980s and its involvement in the drug trafficking business, the Camorra has acquired a strong presence in other European countries, particularly Spain. Usually, Camorra clans maintain close contact with South American drug cartels, which facilitates the arrival of drugs in Europe.

According to Naples public prosecutor Giovanni Melillo, during a 2023 speech of the Antimafia Commission, the most powerful groups of the Camorra in the present day are the Mazzarella clan and the Secondigliano Alliance. The latter is an alliance of the Licciardi, Contini and Mallardo clans.[5]

History

[edit]

The origins of the Camorra are unclear. It may date to the 17th century[6] as a direct Italian descendant of a Spanish secret society, the Garduña, founded in 1417. Recent historical research suggests that the Garduña did not exist and its legendary status was based on a 19th-century fictional book.[7][8] According to historian John Dickie the Garduña was a fictional organisation that appeared from nowhere in a very popular French pulp novel published in 1845. The author probably based the story on Miguel de Cervantes’ short story Rinconete and Cortadillo. An Italian translation in 1847 spread the myth in Italy.[9]

More likely, the Camorra developed in the 18th century. Officials of the Kingdom of Naples may have introduced the organisation to the area, or it may have developed gradually from small criminal gangs operating in Neapolitan society near the end of the 18th century.[10] The first official use of camorra as a word dates from 1735, when a royal decree authorised the establishment of eight gambling houses in Naples. The word is likely a blend, or portmanteau, of "capo" (boss) and a Neapolitan street game, the "morra".[10][11] After gambling was prohibited by the local government, some people started making the players pay for protection against the attentions of passing police.[10][12][13]

The Camorra emerged during the chaotic power vacuum between 1799 and 1815, when the Parthenopean Republic was proclaimed on the wave of the French Revolution and the Bourbon Restoration. The first official mention of the Camorra as an organisation dates from 1820, when police records detail a disciplinary meeting of the Camorra, a tribunal known as the Gran Mamma. That year the first written statute of the Camorra, the frieno, was discovered, indicating a stable organisational structure in the underworld. Another statute was discovered in 1842, related to initiation rites and funds set aside for the families of those imprisoned. The organisation was also known as the Bella Società Riformata, Società dell'Umirtà or Onorata Società.[14][15]

The evolution into more organised formations indicated a qualitative change: the Camorra and camorristi were no longer local gangs living off theft and extortion; they had a fixed structure and some kind of hierarchy. Another qualitative leap was the agreement between the liberal opposition and the Camorra, following the defeat of the 1848 revolution.[16] The liberals realised that they needed popular support to overthrow the king. They turned to the Camorra and paid them because the camorristi were the leaders of the city's poor. The new police chief, Liborio Romano, appealed to the head of the Camorra, Salvatore De Crescenzo, to maintain order and appointed him as head of the municipal guard.[17] In a few decades, the Camorra had developed into power brokers.[14] In 1869, Ciccio Cappuccio was elected as the capintesta (head-in-chief) of the Camorra by the twelve district heads (capintriti), succeeding De Crescenzo after a short interregnum.[18] Nicknamed "The king of Naples" ("o rre 'e Napole"), he died in 1892.[19][20]

Following Italian unification in 1861, the government made attempts to suppress the Camorra.[21] From 1882, it conducted a series of manhunts. The Saredo Inquiry (1900–1901), established to investigate corruption and bad governance in Naples, identified a system of political patronage run by what the report called the "high Camorra":

The original low camorra held sway over the poor plebs in an age of abjection and servitude. Then there arose a high camorra comprising the most cunning and audacious members of the middle class. They fed off trade and public works contracts, political meetings and government bureaucracy. This high camorra strikes deals and does business with the low camorra, swapping promises for favours and favours for promises. The high camorra thinks of the state bureaucracy as being like a field it has to harvest and exploit. Its tools are cunning, nerve and violence. Its strength comes from the streets. And it is rightly considered to be more dangerous, because it has re-established the worst form of despotism by founding a regime based on bullying. The high camorra has replaced free will with impositions, it has nullified individuality and liberty, and it has defrauded the law and public trust.[22][23]

The inquiry introduced the terminology of "high Camorra", as having a bourgeois character, and distinct from the plebeian Camorra proper. The two groups were in close contact through the figure of the intermediary (faccendiere).[24]

From the rich industrialist who wants a clear road into politics or administration to the small shopowner who wants to ask for a reduction of taxes; from the businessman trying to win a contract to a worker looking for a job in a factory; from a professional who wants more clients or greater recognition to somebody looking for an office job; from somebody from the provinces who has come to Naples to buy some goods to somebody who wants to emigrate to America; they all find somebody stepping into their path, and nearly all made use of them.[25]

Scholars dispute whether the "high Camorra" was an integral part of the Camorra proper.[23] Although the inquiry did not prove specific collusion between the Camorra and politics, it did reveal the patronage mechanisms that contributed to corruption in the municipality.[22] The society's influence was weakened, which was exemplified by the defeat of all of their candidates in the 1901 Naples election. In the early 20th century, given the poverty of Naples and the region, many camorristi emigrated to the United States.[26]

The Camorra received another blow with the Cuocolo Trial (1911–1912). The trial was ostensibly to prosecute those charged with the murder on 6 June 1906 of the Camorra boss Gennaro Cuocolo and his wife, who were suspected of being police spies. The main investigator, Carabinieri Captain Carlo Fabbroni, transformed the trial into one against the Camorra as a whole, intending to use it to strike the final blow to the Camorra.[27][28]

The trial attracted much attention among newspapers and the general public, both in Italy and the United States, including by Pathé's Gazette.[29] The hearings began in 1911. After 17 months, the often tumultuous proceedings ended with a guilty verdict on 8 July 1912 against defendants who included 27 leading Camorra bosses. They were sentenced to a total of 354 years' imprisonment. Enrico Alfano, the main defendant and nominal head of the Camorra, was sentenced to 30 years.[27][30][31][32]

The Camorra has never been a unified, centralised organisation, but instead a loose confederation of different, independent clans, groups or families. Each group is bound by kinship ties and controlled economic activities that took place in its particular geographic territory. Each clan takes care of its own business, protects its territory, and sometimes tries to expand at another group's expense. There is some minimal coordination to avoid mutual interference. The families compete to maintain a system of checks and balances among equal powers.[33]

One of the Camorra's strategies to gain social prestige was and remains political patronage. The family clans became the preferred go-betweens of local politicians and public officials because of their grip on the community. In turn, the family bosses used their political sway to assist and protect their clients against the local authorities. Through a mixture of brute force, political status, and social leadership, the Camorra clans gained ground as middlemen between the local community and bureaucrats and politicians at national level. They granted privileges and protection, and intervened in favour of their clients, in return for their silence and connivance against local authorities and the police. With their political connections, the heads of the major Neapolitan families became power brokers in local and national political contexts, providing Neapolitan politicians with broad electoral support, and in return receiving benefits for their constituency.[33]

Activities

[edit]Compared to the Sicilian Mafia's pyramidal structure, the Camorra has more of a 'horizontal' structure.[34] As a result, Camorra clans act independently of one another and are more prone to feuding. This, however, makes the Camorra more resilient when top leaders are arrested or killed, as new clans and organisations emerge from the remnants of old ones. Clan leader Pasquale Galasso stated in court, "Campania can get worse because you could cut into a Camorra group, but another ten could emerge from it."[35]

In the 1970s and 1980s, Raffaele Cutolo made an unsuccessful attempt to unify the Camorra families in the manner of the Sicilian Mafia, by forming the New Organized Camorra (Nuova Camorra Organizzata or NCO). Drive-by shootings by camorristi often result in casualties among the local population but such episodes are often difficult to investigate because of the widespread practise of omertà (code of silence). According to a report published in 2007 by Confesercenti, the second-largest Italian trade organisation, the Camorra control the milk and fish industries, the coffee trade, and over 2,500 bakeries in Naples.[36]

In 1983, Italian law enforcement estimated that there were about a dozen Camorra clans. By 1987, the estimate had risen to 26, and in the following year to 32.[37] Roberto Saviano, an investigative journalist and author of Gomorra, an exposé of the activities of the Camorra, says that this sprawling network of clans now dwarfs the Sicilian Mafia, the 'Ndrangheta and southern Italy's other organised gangs, in numbers, in economic power and in ruthless violence.[38]

In 2004 and 2005, the Di Lauro clan and the so-called Scissionisti di Secondigliano fought a bloody feud which came to be known in the Italian press as the Scampia feud. The result was over 100 street killings. At the end of October 2006 a new series of murders took place in Naples between 20 competing clans, costing 12 lives in 10 days. The Interior Minister, Giuliano Amato, decided to send more than 1,000 extra police and carabinieri to Naples to fight crime and protect tourists.[39] Despite this, in the following year there were over 120 murders.[citation needed]

In 2001, the businessman Domenico Noviello from Caserta testified against a Camorra extortionist and subsequently received police protection. In 2008 he refused further protection and was killed one week later.[40]

In recent years, various Camorra clans have been allegedly using alliances with Nigerian drug gangs and the Albanian mafia. Augusto La Torre, the former La Torre clan boss who became a pentito, is married to an Albanian woman; the first foreign pentito, a Tunisian, admitted to being involved with the feared Casalesi clan of Casal di Principe. The first town in which the Camorra sanctioned stewardship by a foreign clan was Castel Volturno, which was given to the Rapaces, clans from Lagos and Benin City in Nigeria. This allowed them to traffic cocaine and women in sexual slavery before sending them across Europe.[41]

Waste crisis

[edit]Since the 1980s, the Camorra has taken over the handling of waste disposal in the region of Campania. By December 1999, all regional landfills had reached capacity.[42] Reports in 2008 stated that the crisis was caused at least in part by the Camorra, which created a lucrative business in the municipal waste disposal business, mostly in the triangle of death. With the complicity of industrial companies, heavy metals, industrial waste, and chemicals and household waste are frequently mixed together, then dumped near roads and burned to avoid detection, leading to severe soil and air pollution.[43][44]

According to Giacomo D'Alisa et al., "the situation worsened during this period as the Camorra diversified their illegal waste disposal strategy: 1) transporting and dumping hazardous waste in the countryside by truck; 2) dumping waste in illegal caves or holes; 3) mixing toxic waste with textiles to avoid explosions and then burning it; and 4) mixing toxic with urban waste for disposal in landfills and incinerators."[42]

A Camorra member, Nunzio Perella was arrested in 1992, and began collaborating with authorities; he had stated "the rubbish is gold."[42] The boss of the Casalesi clan, Gaetano Vassallo, admitted to systematically working for 20 years to bribe local politicians and officials to gain their acquiescence to dumping toxic waste.[45][46]

The triangle of death and the waste management crisis is primarily a result of government failure to control illegal waste dumping. The government had attempted to mandate recycling and waste management programs, but were unable, causing the expansion of opportunities for illegal activities, which caused further barriers to solve the waste crisis.[42][47][48][49]

In November 2013, a demonstration by tens of thousands of people was held in Naples in protest against the pollution caused by the Camorra's control of refuse disposal. Over a twenty-year period, it was alleged, about ten million tonnes of industrial waste had been illegally dumped, with cancers caused by pollution increasing by 40–47%.[50]

Efforts to fight the Camorra

[edit]The Camorra has proven to be an extremely difficult organisation to fight within Italy. During the 1911–12 trial, Fabroni gave testimony on how complicated it was to successfully prosecute the Camorra: "The Camorrist has no political ideals. He exploits the elections and the elected for gain. The leaders distribute bands throughout the town, and they have recoursed to violence to obtain the vote of the electors for the candidates whom they have determined to support. Those who refuse to vote as instructed are beaten, slashed with knives, or kidnapped. All this is done with assurance of impunity, as the Camorrists will have the protection of successful politicians, who realize that they cannot be chosen to office without paying toll to the Camorra."[51]

Unlike the Sicilian Mafia, which has a clear hierarchy and a division of interests, the Camorra's activities are much less centralised. This makes the organisation much more difficult to combat through crude repression.[52] In Campania, where unemployment is high and opportunities are limited, the Camorra has become an integral part of the fabric of society. It offers a sense of community and provides the youth with jobs. Members are guided in the pursuit of criminal activities, including cigarette smuggling, drug trafficking, and theft.[53]

The government has made an effort to combat the Camorra's criminal activities in Campania. The solution ultimately lies in Italy's ability to offer values, education and work opportunities to the next generation. However, the government has been hard pressed to find funds for promoting long-term reforms that are needed to improve the local economic outlook and create jobs.[53] Instead, it has had to rely on limited law enforcement activity in an environment that has a long history of tolerance and acceptance of criminality and is governed by the omertà.[54]

Despite the overwhelming magnitude of the problem, law enforcement officials continue their pursuit. The Italian police are coordinating their efforts with Europol and Interpol to conduct special operations against the Camorra. The Carabinieri and the Financial Police (Guardia di Finanza) are also fighting criminal activities related to tax evasion, border controls, and money laundering. Prefect Gennaro Monaco, Deputy Chief of Police and Chief of the Section of Criminal Police cites "impressive results" against the Camorra in recent years, yet the Camorra continues to grow in power.[55]

In 1998, police took a leading Camorra figure into custody. Francesco Schiavone was caught hiding in a secret apartment near Naples behind a sliding wall of granite. The mayor of Naples, Antonio Bassolino, compared the arrest to that of Sicilian Mafia chief Salvatore Riina in 1993.[56] Schiavone is now serving a life sentence after a criminal career which included arms trafficking, bomb attacks, armed robbery, and murder.[citation needed]

Michele Zagaria, a senior member of the Casalesi clan, was arrested in 2011 after eluding police for 16 years. He was found in a secret bunker in the town Casapesenna, near Naples.[57] In 2014, clan boss Mario Riccio was arrested for drug trafficking in the Naples area. Around the same time 29 suspected Camorra members were also arrested in Rome.[58]

The arrests in the Campania region demonstrate that the police are not allowing the Camorra to operate without intervention. However, progress remains slow, and these minor victories have done little to loosen the Camorra's grip on Naples and the surrounding regions.[53]

In 2008, Italian police arrested three members of the Camorra crime syndicate on 30 September 2008. According to Gianfrancesco Siazzu, commander of the Carabinieri police, the three were captured in small villas on the coast of Naples. All three had been on Italy's 100 top most wanted list. Police seized assets valued at over 100 million euros and also weapons, including two AK-47 assault rifles that may have been used in the shooting of six Africans on 18 September 2008. Police found pistols, Carabinieri uniforms and other outfits that were used to disguise members of the operation. During the same week, a separate operation netted 26 additional suspects in Caserta. All were believed to belong to the powerful Camorra crime syndicate that operates in and around Naples. The suspects were charged with extortion and weapons possession. In some cases, the charges also included murder and robbery. Giuseppina Nappa, the 48-year-old wife of a jailed crime boss, was among those arrested. She is believed to be the Camorra's local paymaster.[59]

The Italian state confiscated €30 million including real estate in Luxembourg belonging to Angelo Grillo, a businessman from Marcianise, considered very close to the Belforte clan.[60] Grillo also owned the company Lynch Invest SA based in the country. In the name of this company, he purchased real estate in Campania and Sardinia.[61]

In November 2018, Italian police announced the arrest of Antonio Orlando, suspected of being a major figure in the Camorra.[62]

In February 2019, Ciro Rinaldi, boss of the Rinaldi clan, was arrested in a house in the region of San Pietro a Patierno, he is accused of the double murder of Raffaele Cepparulo, member of a small gang linked to the Mazzarella clan, and Ciro Colonna, an innocent victim. Rinaldi is also considered responsible for the murder of Vincenzo De Bernardo, also linked to the Mazzarellas.[63] At the time of his arrest, his clan was considered one of the most powerful clans of the Camorra, having all the eastern area of the city of Naples under its control and having as allies the Secondigliano Alliance.[64][65] On 18 September 2019, Ciro Rinaldi was sentenced to life imprisonment, considered to be the mastermind behind the murders of Cepparulo and Colonna.[66] According to the reports, Rinaldi reportedly ordered Cepparulo's death believing Cepparulo was planning to kill him to give "pleasure" to the Mazzarella clan, historical enemies of the Rinaldi clan.[67]

In March 2019, Marco Di Lauro, the second most wanted man in Italy, was arrested after spending 14 years on the run. He is the fourth son of ex-Camorra boss Paolo Di Lauro. In 2010, an informant said that he was responsible for at least four murders.[68]

In June 2019, the Italian police arrested more than 120 members of the Secondigliano Alliance, the alliance created by the Licciardi, Contini and Mallardo clans, in an anti-Camorra operation. The police also confiscated €130 million. Among those who were arrested were the wives of the bosses of the Bosti, Mallardo, Licciardi and Contini clans, but also their lieutenants, children, grandchildren and entrepreneurs who worked for the alliance.[69][70] The historical female boss Maria Licciardi managed to escape from the arrest in the operation, and is now considered a fugitive.[71] Seven members of the organization were arrested in Spain, Netherlands, South America and in the Balkans, places where they were running illicit business on behalf of the Alliance.[72]

On 12 July 2019, the Italian police confiscated €300 million, including 600 houses, lands, 16 cars and bank accounts belonging to Antonio Passarelli, a businessman believed to be connected to the Di Lauro clan, Puca clan, Aversano clan, Mallardo clan, Verde clan, Perfetto clan and to the Scissionisti di Secondigliano.[73]

On 10 August 2019, an operation of the police arrested six important members of the Rinaldi clan, particularly members of the Reale faction. They are accused of drug trafficking, extortion and illegal possession of weapons. The organization, once considered one of the most prominent, suffered hard blows in 2019, with the arrests of most of its leaders and important figures.[74]

On 21 August 2019, Giuseppe Chirico, included in the list of the most dangerous fugitives in Italy, was arrested in the Ciampino airport, where he landed after a brief holiday abroad. Chirico is considered a prominent member of the Scarpa, linked to the powerful Gallo-Cavalieri clan from Torre Annunziata, dedicated in particular to international drug trafficking. He was wanted since January 2018 and was using a fake identity at the time of his arrest.[75]

On 24 September 2019, the Italian police arrested Salvatore Ferro, step brother of Gaetano Beneduce, head of the historical Beneduce-Longobardi clan, based in Pozzuoli. Ferro, according to investigations, led the Ferro faction of the clan since the death of his brother Rosario Ferro, known as 'Capatosta, in 1998. Now he will serve two years and five months in prison.[76][77]

In September 2019, Pasquale Puca, known as ‘o minorenne, head of the Puca clan and nephew of Giuseppe Puca, was sentenced to life in prison. Puca is held responsible for the murder of Francesco Verde, known as ‘o negus, then leader of the Verde clan, happened in 2007. Between the end of the 1980s and the 1990s, the Verde clan fought with the Puca and Ranucci clans, a clash to which numerous murders were attributed.[78]

In October 2019, the Direzione Investigativa Antimafia seized €1.5 million belonging to Annalisa De Martino, the former partner of the boss Giuseppe Gallo. The Gallo clan has control over illegal activities such as extortion, drug trafficking and money laundering in the areas of Boscotrecase, Boscoreale and Torre Annunziata. De Martino was considered to be in charge of the financial management of the organization.[79][80]

On 23 October 2019, the Italian police dismantled the Montescuro clan, arresting 23 important members of the organisation. The clan was headed by the elderly boss Carmine Montescuro, nicknamed 'Zì Menuzzo' , a leader of remarkable criminal charisma, who for at least 20 years played the role of mediator in the wars between various clans. According to the investigations, due to his mediation skills, he was able to put the Missos [it], the Mazzarellas and the Continis at the same table when the war between their organisations was at its peak in the early 2000s. Montescuro also had a good relationship with Marco Mariano, boss of the Mariano clan in the 1990s. Despite his advanced age, the Court of Naples authorized his arrest and transfer to prison; however, after less than two weeks, he was transferred from jail to house arrest for health reasons.[81] Montescuro was also known for his passion for gambling, and was often in Monte Carlo, where he reportedly spent large amounts of money.[82][83]

In November 2019, Raffaele Romano, a prominent affiliate of the De Luca Bossa clan, decided to move to the side of the State, becoming a pentito.[84] According to reports, the De Luca Bossa clan, now the most powerful clan of Ponticelli and of much of the Vesuvian area, could soon crumble under the declarations of the new pentito.[85]

On 6 November 2019, the Carabinieri arrested Federico Rapprese, linked to the Rannucci clan and included in the list of the most dangerous fugitives. Rapprese was wanted since February 2018, accused of the attempted murder of Antonio Marrazzo, brother of the head of the Marazzo clan, happened in December 2006.[86]

On 8 November 2019, Antonio Abbinante, considered the new boss of Scampia and the current head of the Abbinante clan [it], was arrested by the police. Abbinante was intercepted in Mugnano di Napoli along with two bodyguards.[87]

On 11 November 2019, Marco Di Lauro was sentenced to life imprisonment, considered the mastermind behind the ambush in which Attilio Romanò, an innocent victim, was killed. The murder took place in January 2005, when the assassins of the Di Lauro clan mistook Romanò for the nephew of the boss Rosario Pariante, one of the Scissionistis with whom the Di Lauro clan was at war.[88]

On 12 November 2019, 20 members of the Cesarano clan were arrested, accused of Camorra association, extortion and drug trafficking. The organization is particularly active in Ponte Persica and Pompei. In May 2019, the police dismantled a scheme in which the clan had a privileged channel to the Netherlands, obtaining the monopoly on shipments of flowers, bulbs and pottery from the country.[89]

On 11 December 2019, Giuseppe Polverino and Giuseppe Simioli, former leaders of the Polverino clan, were sentenced to life imprisonment. They were held responsible for the murder of Giuseppe Candela, which happened in July 2009. According to the investigations, Candela, who was a member of the clan, was killed because he was managing his business independently and no longer responding to the clan.[90]

In February 2020, four members affiliated to the Rinaldi clan were arrested, among which are also Rita and Francesco Rinaldi, sons of the late boss of the clan, Antonio Rinaldi known as 'O Giallo (killed in 1989), as well nephews of Ciro Rinaldi.[91] They are accused of usury, extortion and attempted extortion with the aggravating circumstance of the mafia method.[91]

Also in February 2020, the Guardia di Finanza seized a company that, according to the Antimafia, belonged to the Cesarano clan, from Castellammare di Stabia, and was headed by Antonio Martone and Giovanni Esposito, both in prison, and brothers-in-law of Luigi Di Martino, boss of the Cesarano clan. The purpose of this company was to stand between traders and carriers in order to impose the services and tariffs of the clan on them. The Guardia di Finanza estimated the turnover of the business was around €2 million.[92][93]

On 17 March 2020, the Italian police arrested five members of the Aprea-Cuccaro clan accused of extortion and attempted extortion with aggravating circumstances.[94] According to the investigators, the building contractors in the area of Barra, the clan's stronghold, victims of extortion by part of the clan, were summoned to the 'villa' of the boss Antonio Acanfora, also arrested in the operation and considered the current regent of the Aprea's wing inside the organizations. The current actions by members of the Aprea-Cuccaro clan would be an expression of the new criminal alliance formed with the De Luca Bossa clan and the Rinaldi clan in order to control the entire eastern territory of Naples.[95]

In May 2020, a small group of drug dealers led by Anna Gallo, a 74-year-old woman, was overthrown by the Italian police in Torre Annunziata. Anna Gallo, known as "ninnacchera", is the widow of a local Camorra affiliate Ernesto Venditto, killed in an ambush in 1999. In the operation were arrested 22 people, including 9 women.[96][97]

Also in May 2020, the Italian State confiscated €7 million to a businessman linked to the Zagaria's faction of the Casalesi clan. Among the seized goods were 25 bank accounts, eight companies, 18 commercial premises, 32 houses, seven garages and four plots of land.[98][99] In the same week, autoritires confiscated more assets for a total value of over €22 million belonging to Vincenzo Zangrillo, another businessman linked to the Casalesi. In this operation were seized 200 vehicles, 21 hectares of land, six companies and 21 bank accounts.[100] In the past, Zangrillo had been accused of international drug trafficking.[101]

On 3 June 2020, the Italian police dismantled the monopoly of the drug market led by the D'Alessandro clan. According to the police the clan had the total control of the cocaine market in the Sorrento Peninsula, where they also sold drugs to wealthy businessmen. The D'Alessandro clan also used a network of brokers by which they accessed new supply channels, having contacts even with the Bellocco and Pesce 'ndrine, historical 'Ndrangheta groups from Rosarno in Calabria.[102][103]

In June 2020, five Camorra affiliates were arrested in the Province of Naples, that operated between the cities of Nola and Saviano. According to the investigations, they were involved in public contracts in Saviano, such as in the redevelopment of the sewage system and in the management of the waste collection service. The group was also active in the drug market, supplying the local drug dealers.[104]

After months of investigations and joint activities of the Interpol, on 3 June 2020, the Italian government finally obtained the extradition of Salvatore Vittorio from Dominican Republic to Italy. Vittorio was considered the money launderer of the Contini clan in Santo Domingo. According to the Italian authorities, he is accused of mafia-type criminal association and money laundering.[105][106][107]

On 5 June 2020, the Direzione Distrettuale Antimafia seized €10 million of assets from the Polverino clan. Among the seized assets were two villas, two garages, two warehouse-depots, six commercial premises, three plots of land, a school building and a nursery.[108][109]

On 9 June 2020, a Senator of centre-right opposition Forza Italia party, Luigi Cesaro, was placed under investigation, after a police investigation that led to the arrest of 59 affiliates of Camorra clans based in the comune of Sant'Antimo, including three brothers of the politician. The Cesaro family is a well known family in Sant'Antimo, having vast businesses especially in the field of private health and affiliated with the National Health Service.[110] According to the investigations, the Cesaros were involved in a scheme between entrepreneurs, municipal technicians, politicians and well-known representatives of the local organized crime, such as members of the Puca clan.[111][112][113]

Outside Italy

[edit]Despite its origins, it presently has secondary ramifications in other Italian regions, like Lombardy, Piedmont, Lazio and Emilia-Romagna in connection with the centres of national economic power.[114][115][116][117] It has also spread outside the boundaries of Italy, and acquired a foothold in other countries, in particular in Spain, but also in the Netherlands, France, Morocco, United Kingdom, Romania, Switzerland, Peru and Ivory Coast.[118]

France

[edit]The Camorra has been present in France since the early 1980s. The locations with the biggest presence of the organization in the country are the French Riviera, Paris and Lyon. Their biggest objective in the country has always been to create contacts for drug trafficking but also money laundering.[119]

In 1993, the Camorra and the Sicilian Mafia were accused of running a $1.5 billion operation to launder drug money through banks, insurance companies, hotels and casinos in Italy and on the French Riviera, arresting 36 suspects.[120]

Paolo Di Lauro funnelled the proceeds into real estate, buying dozens of flats in Naples, owning shops in France and the Netherlands, as well as businesses importing fur, fake fur and lingerie.[121][122]

In 2014, Antonio Lo Russo, member of the powerful Lo Russo clan and considered the new regent of the clan, and his cousin Carlo Lo Russo were arrested by agents of National Gendarmerie Section de recherches and by Carabinieri when quietly in a bar in Nice. The clan is accused of extortion, drug trafficking and murder. According to the then Minister of the Interior of France, Bernard Cazeneuve, the arrest of Lo Russo was a hard blow for the organized crime in the country.[123]

Ivory Coast

[edit]The La Torre clan was known to launder money in the country with the help of the former chancellor of Salerno, Cesare Salomone.[124]

In June 2019 the operation Spaghetti Connection dismantled an international drug network involving the Camorra and the 'Ndrangheta in Abidjan and Tabou. The police seized 1.19 tons of cocaine, with the value of €250 million in the European market. This operation was the third of its kind in Ivory Coast in less than three years, but the largest by its magnitude. Six Italians, one French and three Ivorians were arrested.[125]

According to Silvain Coué, a French liaison officer, who participated of the operation:

For 20 years, West Africa has become, if not a hub, a very important rebound zone for traffickers.This operation proves that if they thought that Ivory Coast and West Africa could be a sanctuary, they were wrong.[126]

The drug trafficking in the country is said to contribute to the financing of the various jihadist groups in the Sahel, Africa.[127]

Morocco

[edit]Giuseppe Polverino, the leader of the Polverino clan before his arrest, was considered the 'hashish king', due to his monopoly on the importation of hashish from Morocco to Italy via Spain supplying not only all the Camorra clans, but also the 'Ndrangheta, the Sicilian Mafia and the Sacra Corona Unita.[128] The Polverino clan had a monopoly of the hashish trade since 1992. According to one of the pentitos of the clan, Domenico Verde, the hashish was cultivated in the region of Ketama, and arrived by mules in the beginning, but later was modernized and accessible on trucks and cars.[129]

On 18 March 2019 an Italian, suspected of being one of the leaders of the Mazzarella clan, was arrested in the Ourika region, near Marrakech. He had a pursuant to a red notice issued against him by Interpol in January 2019.[130]

On 29 May 2019 Raffaele Vallefuoco, an important member of the Polverino clan, was arrested in the Rabat region. Vallefuoco is considered one of the biggest drug traffickers in Italy and was included on the list of the 50 most wanted fugitives.[131][132]

Netherlands

[edit]According to Francesco Forgione, the former president of the Antimafia Commission, the Camorra is very active in gambling houses and money laundering in the Netherlands. The Camorra also uses the country to counterfeit clothes, and the clans most involved in this illegal activity are the Licciardi clan, the Di Lauro clan and the Sarno clan.[133]

Augusto La Torre, the former leader of the La Torre clan is suspected of having hid hundreds of millions of euros in Dutch banks, as the La Torre clan was very active in the country in the 1990s transporting large cocaine shipments from South America to Naples via the Netherlands.[134]

In 1996, Raffaele Imperiale bought a coffee shop called Rockland Coffee in Amsterdam, where he sold soft drugs and was involved in large scale cocaine trafficking with the Dutch drug trader Rick van de Bunt. Imperiale worked in Amsterdam until 2008. In 2016, two stolen Van Gogh paintings from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam in 2002 were recovered in a villa near Naples, connected to Raffaele Imperiale, accused of being one of the Camorra's prolific drug barons. Imperiale was sentenced to 18 years in absentia for drug offenses.[135] After fleeing the Netherlands to Dubai, he had been seen in the Burj Al Arab hotel.[136]

On 27 November 2019, the DIA with the support of the Dutch police arrested Alfredo Marfella, a drug trafficker working for Camorra clans, in The Hague. Marfella is believed to have played a coordinating role in the drug trade from the Netherlands to Italy.[137][138]

In December 2019, the Dutch police arrested in The Hague, Dario Pasutto, a businessman suspected of smuggling thousands of kilos of cocaine and tens of thousands of kilos of hashish from the Netherlands to Italy. According to the Dutch press, the suspect is a well-known flamboyant entrepreneur, and for many years a Camorra affiliate.[139][140] The arrest of Pasutto is related to the arrests made by the Italian police in Naples in the same week against a group of drug traffickers that were smuggling cocaine from Colombia to the city of Naples with the help of Camorra clans.[141]

Peru

[edit]As Peru is one of the largest cocaine producers in the world, the Camorra's interest in the country is entirely related to the drug trafficking.[142]

In the 1980s, Umberto Ammaturo, a Camorra affiliate, established a virtual monopoly of cocaine trafficking to Italy from Peru, where he benefited from the protection and collusion of important personalities.[143] According to the US DEA, due to his trafficking activities, Ammaturo was one of the chief financiers of the Shining Path guerrilla movement in Peru.[144]

One of the leaders of the Mazzarella clan, Salvatore Zazo, was allegedly involved in a large scheme of international cocaine trafficking from Peru to Europe, with the intention to acquire total control of the Port of Callao; one of his contacts was Gerald Oropeza, one of the biggest drug traffickers in Peru.[145] According to the DEA, Zazo would manage more than U$500 million per year in shipments of cocaine through the ports of the country to Europe.[146]

A 2021 report made by Raúl Del Castillo, general of the National Police of Peru, stressed that Europe is today the main destination of Peruvian cocaine, specifying also that Camorra clans are among the international criminal organizations that have their emissaries "working" in Peru.[147]

The notorious "super cartel" headed by Raffaele Imperiale, one of the major drug traffickers of the Camorra, had a virtual monopoly of the Peruvian cocaine trade, in which the drugs were distributed throughout Europe.[148][149]

Romania

[edit]Camorra clans in Romania deal in money laundering.[118] In 2017, Gaetano Manzo, the accountant of the Sacco-Bocchetti clan, was arrested in his villa in Fizeșu Gherlii. The Sacco-Bocchetti clan is a subgroup of the Licciardi clan and Manzo took care of the accounting of the clan, and often supervised the supply of drugs from abroad.[150]

In 2018, Nicola Inquieto, an Italian businessman with strong ties to Michele Zagaria one of the leaders of the powerful Casalesi clan, was arrested in Romania. Inquieto has built hundreds of apartments through his companies and owns the most modern spa in Argeș County. The prosecutors have also seized 400 apartments in Pitești belonging to his companies. His businesses in the country are valued at several million euros.[151]

On 19 October 2019, Vincenzo Inquieto, right-hand man of Michele Zagaria and brother of Nicola Inquieto, was arrested in the Naples International Airport after returning from Bucharest. According to the Romanian media, since the arrest of his brother Nicola, Vincenzo lived permanently in the country, returning rarely to Italy. And was reportedly taking charge of the vast business the Casalesi clan, particularly the Zagaria's faction, held in Romania.[152][153]

Spain

[edit]According to the journalist Roberto Saviano, Spain (after Italy) is the country most entwined with the Camorra. It is where the Camorra clans established its massive businesses revolving around drug trafficking and money laundering in real estate.[154]

Camorra has been in Spain since the 1980s. The most powerful clan acting in the country is the Polverino clan due to the number of people they have installed and because of the potential of their structure. They have influence in the cities of Alicante, Tarragona, Málaga and Cádiz.[155]

According to the Italian antimafia police, in recent times, the Camorra clans based in Spain have accumulated €700 million as a result of drug trafficking and money laundering in the country.[156]

The presence of the organization in the Costa del Sol is so strong that Camorra bosses refer to it as Costa Nostra' ("Our Coast"), according to Italian journalist Roberto Saviano, a specialist on the Naples criminal underworld.[157]

Another clan with influence in Spain is the Scissionisti di Secondigliano led by Raffaele Amato nicknamed Lo Spagnolo (the Spaniard), because before creating his own clan, he controlled the drug trafficking operation from Galicia to Naples for the Di Lauro clan.[158] Amato was arrested as he left a casino in Barcelona in 2005.[159]

The drug trafficker Pasquale Brunese was arrested in Valencia in 2015, after seven years hiding from the Italian police.[160] He was a member of the De Luca Bossa clan, for whom he worked in the drug trade. In Spain, Brunese owned a restaurant and was living with a false name.[161][162]

In February 2019, the Spanish police arrested 14 members of the notorious Marranella clan. According to the Guardia Civil, the clan is one of the most important and violent criminal organizations dedicated to the international drug trade and is based in the Costa del Sol.[163]

Alfredo Barasso, linked to the bloodthirsty Casalesi boss Giuseppe Setola, was arrested in Valencia and extradited to Italy. Barasso was a "bridge" between Italy and Spain, working for the Casalesi clan in the drugs management in the Barcelona area. After his decision to become a pentito, and afraid of retaliation by the Camorra, Barasso would be willing to return to Spain, where he has wife and children, and pay his penalty there, as provided by the bilateral agreements between the two countries.[164]

According to a 2019 documentary of the Spanish television, Barcelona is the nerve center of the organization outside Italy, exposing the endless business of the Camorra in Catalonia, from the massive drug trafficking to the laundering of huge amounts of money in restaurants, clubs and hotels of the region. The documentary also features an interview with Maurizio Prestieri, former member of the Di Lauro clan arrested in Marbella in 2003 and now pentito, who said that Spain is the favorite place for the camorristi.[165]

Also in 2019, relatives of top members belonging to the Polverino clan claim three million euros to the Spanish State of compensation after their relatives were acquitted by the National Court of the crime of money laundering for which they were arrested in 2013 and tried in 2016. Among the assets seized were six yachts, two Ferrari Testarossa, one Lamborghini, one Harley-Davidson, bank accounts and real estate. The plaintiffs are all relatives of the late Giuseppe Felaco, who was allegedly an important member of the Polverino clan based in the Canary Islands, they assure that this Spanish police operation against their family has been a great economic damage, apart from a moral damage.[166]

On 20 November 2019, the Italian police with the cooperation of the Spanish police, arrested two members of the Polverino clan, who belonged to a major transnational organizational structure, created by the Polverinos, based in Valencia and Naples, that between 2001 and 2012 imported hashish from Morocco via Spain to arrive in the Campania region.[167][168]

Switzerland

[edit]The Camorra has had a presence in Switzerland for more than 50 years, undertaking money laundering but also arms trafficking and drug trafficking. The Casalesi clan is present throughout the country, and according to the investigations into the clan, it has numerous Swiss bank accounts.[169]

In 1992, Ciro Mazzarella, the late boss of the Mazzarella clan, decided to move to Switzerland, after losing a war between Camorra clans in Naples. From his logistics base in Lugano, he created an enviable economic empire with cigarette smuggling that arrived from Montenegro.[170]

In 2017, assets worth €20 million belonging to the Potenza brothers, who are considered to be linked to the Lo Russo clan, were seized in Lugano, including bank accounts in BSI.[171]

United Kingdom

[edit]According to 2020 reports about the Camorra, the United Kingdom is an area of interest to launder money, using finance companies and business activities. The Casalesi clan, through an entrepreneur and alleged financial intermediary, had invested 12 million euros using various companies based in Great Britain.[172]

Antonio Righi, called "Tonino il biondo", was considered by the investigators as a money laudererer on behalf of the Contini and Mazzarella clans in London.[173] Although the two organizations are historically rivals, in England they were represented by the same man. Among the British companies that figured in his scheme, was one registered at a luxurious terraced house not far from Oxford Street in London's West End. The trial built against Righi clearly showed that he understood exactly how modern global finance works. The Italian police confiscated 250 million euros belonging to Righi.[174][175]

Between the mid-1980s and early 2000s, Scotland has had its brush with the Camorra, when Antonio La Torre of Aberdeen was the local "Boss". He is the brother of Camorra boss Augusto La Torre of the La Torre clan which had its base in Mondragone, Caserta. The La Torre Clan's empire was worth hundreds of millions of euros. Antonio had several legitimate businesses in Aberdeen, whereas his brother Augusto had several illegal businesses there. Augusto would eventually become a pentito in January 2003.[176] Antonio was convicted in Scotland and extradited to Italy in 2006 to serve a 13-year sentence; he was released in 2014.[177] With the fall of the La Torre clan in the 2000s, Scotland experienced the disappearance of Camorra in the country, in fact the La Torre clan was overthrown in all the countries it had a massive presence, such as in Italy and in the Netherlands.[178][179]

United States

[edit]The Camorra operated in the United States, primarily in New York City, between the mid-19th century and early 20th century. They rivaled the now defunct Morello crime family for power in New York City. Eventually, they melded with early Italian-American Mafia groups.

In the 1980s, many Camorra members and associates fled the internecine gang warfare and Italian justice, which was directed at suppressing the groups, and immigrated to the United States. According to the FBI, it is believed that nearly 200 Camorra affiliates operate in the country. Although they did not appear to recreate their clan structure in the United States, Camorra members have established a presence in Los Angeles, New York City, and Springfield, Massachusetts.[180] The US law enforcement considers the Camorra to be a rising criminal enterprise, especially dangerous because of its ability to adapt to new trends and forge new alliances with other criminal organizations.[181][182]

In 2012, the Obama administration imposed sanctions on the Camorra as one of four key transnational organized crime groups, along with the Brothers' Circle from Russia, the Yamaguchi-gumi (Japan's largest yakuza organization), and Los Zetas from Mexico.[183]

Alliances with other criminal groups

[edit]Camorra-'Ndrangheta

[edit]According to the media, there have always been alliances between the Camorra and the 'Ndrangheta members. On 26 August 1976, Domenico Tripodo, a powerful 'Ndrangheta boss of the time, was stabbed to death in prison on the request of the De Stefano 'ndrina, and with the help of Camorra boss Raffaele Cutolo, the boss of the Nuova Camorra Organizzata (NCO) who worked with the De Stefano's in drug trafficking.[184]

The Tamanaco operation that ended on 22 June 2010, destroyed a drug trafficking operation managed by the La Torre clan from Mondragone and the Barbaro 'ndrina from Platì. The operation consisted in transporting the drugs from Venezuela and Colombia, through several European ports including the port of Amsterdam. At the port of Livorno, 700 kilos of cocaine were seized.[185]

On 11 May 2016, a criminal alliance between the Sinti criminal organization Casamonica clan, members of the Camorra, and affiliates from the 'Ndrangheta's of Polistena, Taurianova and Melicucco was dismantled by the police. €25 million were seized.[186]

On 21 March 2018, 19 arrests were made in Rome of alleged members belonging to the Licciardi clan of the Camorra and members of the Filippone 'ndrina and Gallico 'ndrina accused of drug trafficking.[187]

In 2019, investigations of the Italian police reveals links between the Contini clan and the Crupi brothers, members of the powerful Commisso 'ndrina. Both organizations are reportedly cooperating in the drug trafficking business.[188]

Camorra-Cosa Nostra

[edit]Several Camorra clans have lasting relationships with the Cosa Nostra. Prominent elements of the Mafia such as Salvatore Riina, Leoluca Bagarella, Luciano Leggio and Bernardo Provenzano found themselves in contact with Camorra clans such as the Nuvoletta clan, members of the Camorra such as Michele Zaza and Antonio Bardellino, and with other groups that formed the Nuova Famiglia confederation in the 1980s.[189]

In the past, the Russo clan had links with the Mafia, particularly in the 1980s and 1990s, at the time of the Corleonesi Mafia era.[190]

In 2019, the Direzione Investigativa Antimafia of Catania dismantled a scheme between the Camorra's Mallardo clan and Casalesi clan and members of the powerful Catania's mafia family, led by Vincenzo Enrico Augusto Ercolano, son of Giuseppe Ercolano (deceased, but once an important member of the Catania's mafia) and Grazia Santapaola, the sister of the historical boss Benedetto Santapaola. The DIA also confiscated €10 million in the operation.[191][192]

According to the pentito Domenico Verde, the Polverino clan has a good relationship with the Cosa Nostra families from Palermo, in particular thanks to the drug trafficking business.[193]

Camorra-Sacra Corona Unita

[edit]In 1981, Raffaele Cutolo, entrusted Pino Iannelli and Alessandro Fusco the task of founding an organization in Apulia to be directly controlled by the Nuova Camorra Organizzata, the organization was named Nuova Camorra Pugliese, later called Sacra Corona Unita. This organization operated in various cities of Apulia during the 1980s.[194] But with the downfall of Cutolo, the organisation was no longer a subgroup of the Camorra and was under the leadership of Giuseppe Rogoli.[195]

According to the pentito Antonio Accurso, the Di Lauro clan has several links to the Sacra Corona Unita in question with regards to drug trafficking.[196]

Camorra-Società foggiana

[edit]In September 2019, the Italian police dismantled an international drug trafficking alliance between the powerful Gionta clan of the Camorra, the Società foggiana, also known as the fifth-mafia, and Moroccan drug traffickers.[197] The investigation started in 2016 against a Maghreb gang based in the region of Trentino-Alto Adige. The vast network of drug traffickers, extended from Morocco, passing through Spain, Switzerland and the Netherlands to finally arrive in Trentino and in Bolzano. Arriving in Italy, the drugs were sold in parks, historic centers and near schools by mainly Tunisian and Moroccan pushers. Nineteen people were arrested, four are still wanted in Italy, Spain and in the Netherlands and seventy-three are under investigation. The operation seized over 1 ton of hashish and 2 kg of cocaine.[198][197]

Camorra-South American drug cartels

[edit]The links between the South American drug cartels and Camorra clans dates back to at least the 1980s, having stabilized numerous privileged drug channels from South America to Europe over the years.[199]

According to investigations, the Camorra member Tommaso Iacomino allegedly negotiated with the head of Peruvian and Colombian drug cartels over the cocaine trade.[200]

Giuseppe Gallo called 'o pazz (the crazy one), boss of the Limelli-Vangone clan, is said to having contacts with Colombian drug traffickers able to reach agreements for the purchase of large quantities of cocaine, supplying various clans in the Naples area.[201]

In 2016, Salvatore Iavarone, a broker in South America representing the Tamarisco clan from Torre Annunziata, was arrested in Ecuador.[202] Iavarone is believed to be the main link for the shipment of narcotics from Ecuador to Europe.[203] Other 28 members were arrested during this operation. The police also confiscated €11 million that belonged to Iavarone in Ecuador.[204]

On 4 July 2019, the Guardia di Finanza seized 538 kg of cocaine, worth €200 million, destined for the Camorra in the port of Genoa. According to the reports, the drug was found in 19 bags inside a container that arrived from Colombia. On each of the loaves was a fake €500 note, a symbol known to be that of a new Colombian cartel born of the merger of several other cartels. The container was headed to Naples but was intercepted at the port of Genoa.[205]

On 18 December 2019, the Italian police arrested 12 people, including members of an international drug cartel dedicated to the drug trafficking between Colombia and Italy. According to the investigations, the cocaine brought from Colombia was pure and of high quality, and when it arrived in Italy, it was sold at a "retail" price of 200 euros per gram, all the scheme was managed by Camorra members.[206][207] Among those arrested in the operation was Salvatore Nurcaro, a well known member of the Rinaldi clan.[208]

Camorra-Albanian mafia

[edit]According to the Direzione Investigativa Antimafia, the Albanian mafia has alliances with the Mazzarella clan and with the Scissionisti di Secondigliano, both from Naples and with the Serino clan, from Salerno.[194]

Saviano spoke of the Albanian mafia as a "no longer foreign mafia" to Italy and stressed that the Albanians and Italians have a "brotherly" relationship with each other. Saviano notes that the Camorra feels great affinity with the Albanian crime families because both organizations are based on family ties.[209]

Camorra-Chinese Triads

[edit]According to the expert on terrorist organizations and mafia-type organized crime Antonio De Bonis, there is a close relationship between the Triads and the Camorra, and the port of Naples is the most important landing point of the trades managed by the Chinese groups in cooperation with the Camorra. Among the illegal activities in which the two criminal organizations work together are the human trafficking and illegal immigration aimed at the sexual and labour exploitation of the Chinese compatriots into Italy, the synthetics drug trafficking and the laundering of illicit money through the purchase of real estate.[210]

In 2017, investigators discovered a scheme between the Camorra and the Chinese gangs. They exported industrial waste from Italy to China that guaranteed million-dollar revenues for both organizations. The industrial waste left Prato in Italy and arrived in Hong Kong. Among the Camorra clans involved in this alliance were the Casalesi clan, the Fabbrocino clan and the Ascione clan.[211]

Camorra-Nigerian gangs

[edit]In the beginning, Nigerian immigrants to Italy were not tolerated by the Camorra, but in the 2010s Nigerians and the Camorra began making alliances. Cooperation between the Camorra and Nigerian mafia is mainly in the areas of drug trafficking and prostitution. In particular, Camorra members have allowed the Nigerian gangs to organize the trafficking of women in their territory in exchange for a share on the earnings. The Nigerian mafia produces synthetic drugs independently and sells them with the consent of the Camorra. This alliance, however, may not be stable in the future, as the Nigerians have asked to be treated on par with other Italian mafias, for the fact that they are growing both as a military and as an economic force.[212]

Camorra-Islamic State

[edit]According to numerous articles, the Camorra may be in alliance with the Islamic State. The allegations reached the media after the Italian police seized 14 tonnes of amphetamines produced in Syria by the Islamic State, on July 1, 2020. It is considered the world's largest seizure of amphetamines, with a value of over €1 billion. Camorra clans reportedly bring the drugs to Italy and take a huge cut for helping to distribute them. According to the investigations, the production of these drugs provides the terrorist group (ISIS) with vital revenue for its militant activities.[213][214][215]

Other alliances

[edit]In 1995, the Camorra cooperated with the Russian Mafia in a scheme in which the Camorra would bleach out US$1 bills and reprint them as $100s. These bills would then be transported to the Russian Mafia for distribution in 29 post-Eastern Bloc countries and former Soviet republics.[180] In return, the Russian Mafia paid the Camorra with property (including a Russian bank) and firearms, smuggled into Eastern Europe and Italy.[181]

In the 2000s, the Ukrainian mafia cooperated with Camorra clans in the cigarette smuggling business. The Ukrainians would smuggle the cigarettes from Ukraine and Eastern Europe into Italy, where with the help of the Camorra it supplies the Neapolitan market.[216][217] In recent years, the Contini clan is said to have cooperated in the same scheme with the Ukrainians.[218]

In March 2019, a massive international arms trafficking ring was dismantled by the authorities of Italy and Austria and coordinated by Eurojust. According to the investigations, the alliance between the Camorra and the Austrians lasted for seven years, until the police dismantled the scheme. The Austrians are known to have sold more than 800 new pistols to the Camorra as well as 50 Kalashnikovs and 10 'Scorpion' sub-machine guns, worth a total of €500,000.[219]

According to Gerhard Jarosch, the National Member for Austria at Eurojust:

I dont know any cases, which are so big and where so many weapons have been sold. The new owners are also not "juvenile guarantors" but several members of the Camorra, one of the most dangerous criminal organizations in Europe.[220]

The weapons are believed to have come originally from Eastern Europe taken to Carinthia in Austria with the objective to arrive in Terzigno near Naples.[221] On 15 October 2019, father, 73, and son, 47, were convicted in the Court of Klagenfurt to serve 24 and 20 months respectively in jail.[222][223]

DEA documents sent to the Dutch police exposed what would be a super drug cartel headed by Raffaele Imperiale (Camorra's drugs and arms dealer), Ridouan Taghi (former Dutch most wanted criminal, now in jail), Daniel Kinahan (Irish drug trafficker) and Edin G. (Bosnian drug trafficker). The group was observed by the DEA having meetings in the Burj Al Arab hotel in Dubai, which is the base of the alleged cartel. The meetings took place in 2017; however, it only reached the Dutch media in October 2019. The DEA regards this as one of the world's fifty largest drug cartels, with a virtually monopoly of the Peruvian cocaine and controlled around a third of the cocaine trade in Europe. Yet, according to the DEA documents, the destination for all the drugs shipments were Dutch ports.[224][225][226]

In 2005, it was alleged the Camorra created safe houses, forged documents, firearms, and explosives to Al-Qaeda in return for narcotics, which are brought into Italy via the Adriatic Sea.[227]

Current status

[edit]With most of the old Camorra clans decapitated, and their bosses either dead or arrested, the organization is experiencing a rise in youth criminal gangs trying to take their places. This phenomenon is called Paranza, Camorra terminology for a criminal group led by youngsters or "small fish". Whilst the older bosses often operated out of the limelight, these young criminals broadcast their exploits on social media, posing in designer clothes and with €200 bottles of champagne.[228]

In 2015, 19 year-old Emanuele Sibillo, considered one of the first young and leading bosses of this new generation, was shot dead by a rival baby gang.[229] Most of these young criminals are children of Camorra members that are currently in jail.[230]

According to Felia Allum, author of book The Invisible Camorra: Neapolitan Crime Families across Europe:

We can clearly see the baby gangs are criminals, or people who want to have criminal careers. But there's a vacuum, because the traditional families have lost their leaders. In the centre of Naples the bosses are either in prison or they've become state witnesses, so there's this kind of space for younger kids to appear. They're 17 or 18 with criminal ambition, and they've got a sense of identity of what they want to do.[231]

However, according to Peppe Misso, called ’o nasone, former boss of the Misso clan for over 40 years and now pentito, this young generation of criminals are managed by the "real" Camorra clans, shifting the public attention to these baby gangs while they do their business in silence. According to Misso, the real power of the organization is now in the hands of the Licciardi clan, Mallardo clan, Moccia clan and Contini clan.[232]

On 2 September 2018, Ciro Mazzarella, one of the last historical godfathers of the Camorra, and head of the Mazzarella clan, died in his villa in the affluent neighbourhood of Posillipo, Naples, at the age of 78.[233]

According to reports, in 2019, after the arrest of Marco Di Lauro, leader of the Di Lauro clan and fourth son of Paolo Di Lauro, the Contini clan became the most powerful clan of the Camorra, thanks to no internal split, and not having affiliates that became collaborators of justice. The clan is present in the drugs trafficking, extortion, betting and counterfeiting, also investing hundreds of millions of euros in various countries of Europe.[234]

On 23 April 2019, the powerful boss Mario Fabbrocino, leader of the Fabbrocino clan, died in the hospital of the Parma prison, where he was serving a life sentence for ordering the murder of Roberto Cutolo, Raffaele Cutolo's only son, in 1990.[235] He was known as the boss dei due mondi (boss of two worlds) due to his drug trafficking connections in South America.[236]

Since 26 June 2019, Maria Licciardi was considered the most wanted fugitive belonging to the Camorra, after she managed to escape the huge police operation against her clan.[237] However, on 12 July 2019, the Court of Naples annulled the preventive detention against Licciardi, sharing the legal questions raised by her lawyer, Dario Vannetiello.[238] She was arrested again at Rome's Ciampino airport by Carabinieri on the orders of Naples prosecutors, alleged to have been running extortion rackets as head of the Licciardi Camorra clan, on 7 August 2021 when attempting to travel to Spain.[239]

On 11 July 2019, Anna Terracciano, known as ‘a Masculona, boss of the Terracciano clan, died after suffering from an unknown illness. Terraciano had taken control of the clan after the death of her brother Salvatore, known as ‘o Nirone, in 2016. She has always been very feared and respected for her impetuous nature. According to the media, she is the figure that has well represented the image of the women inside the Camorra, the female symbol of leadership when men are detained or dead.[240]

According to the reports of the DIA about the Camorra, the Mazzarella clan, despite the bloody war against the Rinaldi clan, is still one of the most powerful organizations in Campania, dominating the territory in various neighbourhoods, and having numerous groups under their influence, as the Ferraiuolo clan.[241]

After a time inactive, the De Luca Bossa clan is believed to be gaining power again in the eastern area of Naples, specifically in Ponticelli, thanks to the merger with emergent groups as the Minichini and Schisa.[242] The clan was founded by Antonio De Luca Bossa, known as ‘O sicco, in the 1990s, and was famous for the bloody war against the once powerful Sarno clan. In 1998, ‘O sicco made the first attack with a car bomb in the Camorra's history, killing Luigi Amitrano, the nephew of the boss Vincenzo Sarno, the real target of the ambush.[243] Antonio's father was a member of the Nuova Camorra Organizzata, and died from natural causes in 2008 after 18 years in jail.[244]

On 11 September 2019, Antonino Di Lorenzo, known as o' lignammone, was killed in an ambush near his house in Casola di Napoli.[245] Di Lorenzo was a notorious drug trafficker, dubbed by the media 'the king of drug trafficking in the Monti Lattari region'.[246] According to the Direzione Investigativa Antimafia, he was specialized in the industrial production of marijuana, flooding the illegal drug market, supplying market squares from Castellammare di Stabia to Sorrento[247] and in recent years was at the center of numerous investigations about drug trafficking.[248] His murder is believed to be connected with the feud for control of vast marijuana plantations in the mountainous area of Monti Lattari. Yet, according to the investigations, the killing happened thanks to the 'permission' of the clans from Castellammare di Stabia, who have always supervised the immensely lucrative marijuana trade from the region.[249]

On 30 October 2019, the release of two affiliates belonging to the Beneduce-Longobardi clan made the media headlines after they were received with a huge party in the neighborhood of Monterusciello, Pozzuoli. Giovanni Illiano, 48, and Silvio De Luca, 41, were released after 8 years and 10 years in prison, respectively. More than a hundred of relatives and friends were waiting for them for a party with champagne, flashing nightclub lights, a large fireworks display and a concert of Anthony, a well known neomelodic singer of the area.[250] The fact, documented with photos and videos sent through social networks, caused outrage in the population, and is being investigated by the Italian Police, as it was not authorized by the Municipality of Pozzuoli or by the police.[251][252]

On 21 November 2019, Feliciano Mallardo, brother of Giuseppe and Francesco Mallardo, was found dead inside his car. According to the investigations, he would have suffered a heart attack.[253] Feliciano, who had taken the reins of the Mallardo clan after his brothers ended up in jail, was known as ‘o Sfregiato.[253]

According to numerous 2019 reports, the most powerful clans of the Camorra are the Secondigliano Alliance and the Mazzarella clan. Both clans remain with full dominance of their territories while most of city experiences the growth of small and violent gangs headed by young guys between 17 and 25 years old.[254][255]

In May 2020, Patrizio Bosti, one of the most powerful Camorra bosses who is still alive and one of the leaders of the Secondigliano Alliance, was released from prison. Bosti also claimed inhumane treatment while in prison, and will be compensated by the Italian state. The Camorra boss, that was serving a prison sentence since his arrest in Spain in 2008, should have been released from prison in 2023, however he was charged for three years and the halfway between early release and the time calculated as credit for the "inhuman treatment".[256][257] On May 16, 2020, Bosti was rearrested. The new prison order concerns a recalculation of the sentence by the Emilia-Romagna judiciary, as he was serving his sentence in the region, on the basis of documents provided by the Naples Public Prosecutor. According to the authorities, Bosti has to serve another six years in jail.[258][259]

In June 2022, the notorious Camorra boss Cosimo Di Lauro died in prison. Di Lauro was considered an icon of the Camorra, a ruthless criminal who has become a role model for young people for his look and the storytelling about him.[260]

In popular culture

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2014) |

- Camorra is a 1972 film, directed by Pasquale Squitieri, starring Fabio Testi and Jean Seberg.

- "Commendatori", an episode of The Sopranos which features the Camorra. One of the Camorra's members, Furio Giunta then joins the DiMeo crime family of the American Mafia.

- The Professor (1986), directed by Giuseppe Tornatore. Vaguely inspired by the real story of NCO boss, Raffaele Cutolo. Cutolo is played by Ben Gazzara, with the Italian voiceover done by Italian actor Mariano Rigillo.

- Roberto Saviano's 2006 book Gomorra investigates the activities of the Camorra in Italy, especially in the Provinces of Naples and Caserta. Matteo Garrone adapted the book into a 2008 film, Gomorra, describing low-level Camorra foot-soldiers, and in 2014 into a TV series of the same name.

- The 2009 film Fortapàsc (English: Fort Apache Napoli) directed by Marco Risi about the brief life and death of journalist Giancarlo Siani, murdered by camorrisiti from the Nuvoletta clan.[261]

- The opera I gioielli della Madonna by Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari features the Camorra as part of the plot.

- The story of Raffaele Cutolo also inspired one of the most famous songs of Fabrizio De André, entitled Don Raffaé (Clouds of 1990).

- The Camorra (depicted as a hooded secret society) appear as villains in an episode of The Wild Wild West, "The Night of the Dancing Death".

- In an episode of Archer (Season 4, Episode 11) when a plot to murder the pope was being carried out by the Camorra. After being told that they had succeeded in saving the pope, they are informed of the bad news: That they had killed Camorra members.

- In the Japanese light novel series and anime Baccano!, a handful of the main characters are part of the Camorra group known as the Martillo Family, and become quite insulted if they are mistaken for the Mafia.

- Elena Ferrante's four Neapolitan Novels are concerned with the damage done by the Camorra portrayed as the two Solara brothers.

- In Rei Hiroe's manga Black Lagoon, during the "El baile De La Muerte"/"Roberta's Blood Trail" arc, a man called Tomazo makes his appearance. Tomazo is on the side of the Italian mob leader Ronnie the jaws. Later it is revealed that Tomazo is a member of the Camorra, and his surname Falcone as well.

- In John Wick: Chapter 2, main antagonist Santino D'Antonio is a top member of the Camorra.

- In the short story "The Fate of Faustina" by E. W. Hornung, it is revealed that the main character and criminal-in-hiding A. J. Raffles has made an enemy of a high-level member of the Camorra from his time spent in Italy. In the sequel story, "The Last Laugh", the Camorra try to realize that threat and kill Raffles; however, Raffles not only saves himself from his attackers but also tricks them into poisoning themselves.

- In The Equalizer 3, Robert McCall (Denzel Washington) confronts Camorra crime lord and main antagonist Vincent Quaranta and his brother Marco to free a small town in South Italy from their control.

See also

[edit]- List of members of the Camorra

- List of Camorra clans

- Banda della Magliana

- Sacra Corona Unita

- Castel Volturno massacre

References

[edit]- ^ "FBI Italian/Mafia". FBI. Archived from the original on 24 May 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ Gayrau, Jean-François (2005). Le Monde des mafias: Géopolitique du crime organisé [The World of Mafias: Geopolitics of Organized Crime] (in French). Paris: Odile Jacob. p. 86. ISBN 9782738187338.

- ^ Abadinsky, Howard (2012). Organized Crime. Belmont: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. pp. 122–123. ISBN 9781285401577. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Mafia and Mafia-type organizations in Italy Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, by Umberto Santino, in: Albanese, Das & Verma, Organized Crime. World Perspectives, pp. 82–100

- ^ Mangione, Antonio (15 September 2023). "La mappa della camorra a Napoli, 2 grandi clan e tanti gruppi piccoli gruppi criminali si dividono la città". Internapoli.it (in Italian). Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ L'Italia del Seicento, I. Montanelli R. Gervaso, 1969, Rizzoli Editore, Milano, pag. 193 snippet from Google books Archived 30 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Arsenal & Sanchiz, Una historia de las sociedades secretas españolas, pp. 326-335

- ^ (in Spanish) Interview with historian Hipólito Sánchiz Archived 14 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Minuto digital, 11 December 2006

- ^ Dickie, Blood Brotherhoods, p. 40

- ^ a b c Behan, The Camorra, pp. 9–10

- ^ (in Italian) "Il gioco della morra" Archived 10 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Biblioteca digitale sulla Camorra (accessed 25 May 2011)

- ^ Jacquemet, Credibility in Court, p. 23

- ^ (in Italian) Camorra, alle radici del male, Narcomafie on line, 29 October 2001 Archived 10 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Behan, The Camorra, pp. 12

- ^ Sales, La camorra, le camorre, pp. 72–73

- ^ Fiore, Camorra e polizia nella Napoli borbonica (1840-1860), pp. 190-195

- ^ (in Italian) Paliotti, Storia della Camorra, pp. 149–153

- ^ (in Italian) Paliotti, Storia della Camorra, p. 143

- ^ (in Italian) La morte di Ciccio Cappuccio Archived 8 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Il Mattino, 6 December 1892

- ^ (in Italian) Di Fiore, Potere camorrista: quattro secoli di malanapoli, p. 96–97

- ^ Fiore, Camorra e polizia nella Napoli borbonica (1840-1860), pp. 257-259

- ^ a b (in Italian) La lobby di piazza Municipio: gli impiegati comunali nella Napoli di fine Ottocento Archived 19 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine, by Giulio Machetti, Meridiana, pp. 38–39, 2000

- ^ a b Dickie, Mafia Brotherhoods, pp. 88–89

- ^ (in Italian) L'Inchiesta Saredo Archived 8 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine, by Antonella Migliaccio, Cultura della Legalità e Biblioteca digitale sulla Camorra, Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici dell'Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II (Access date: 5 September 2016)

- ^ Behan, The Camorra, pp. 263–64

- ^ "Camorra – Italian secret society". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 28 November 2016. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ a b The Cuocolo trial: the Camorra in the dock, Museo criminologico (Retrieved 25 May 2011)

- ^ Cuocolo Trial May Be Death Blow of the Camorra, The New York Times, 5 March 1911

- ^ Dickie, Blood Brotherhoods, p. 191 Archived 28 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Behan, The Camorra, p. 23

- ^ Camorrist Leaders Get 30-Year Terms, The New York Times, 9 July 1912

- ^ "Camorra Verdict; All Found Guilty", New York Tribune, 9 July 1912

- ^ a b Jacquemet, Credibility in Court, p. 24

- ^ "Organized Crime, Violence, and Politics | the Review of Economic Studies | Oxford Academic". Archived from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ Behan, Camorra, pp. 184

- ^ "Die Mafia ist Italiens führendes Unternehmen" Archived 19 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Die Welt, 23 October 2007

- ^ Behan, Tom (1996). The Camorra. Routledge. p. 191. ISBN 9780415099875.

- ^ "Man who took on the Mafia: The truth about Italy's gangsters". The Independent. 16 October 2006. Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ Paul Kreiner (6 November 2006). "Mit mehr Polizei gegen die Camorra". Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ^ Hammer, Joshua (6 July 2015). "Why Does the Mob Want to Erase This Writer?". GQ. Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ "Roberto Saviano on the Italian Camorra". Cafe Babel. 8 October 2007. Archived from the original on 1 October 2009.

- ^ a b c d D'Alisa, Giacomo; Burgalassi, David; Healy, Hali; Walter, Mariana (2010). "Conflict in Campania: Waste emergency or crisis of democracy". Ecological Economics. 70 (2): 239–249. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.06.021.

- ^ Mafia at centre of Naples' rubbish mess 9 January 2008. By Emmanuelle Andreani. Der Spiegel: In Naples, Waste Is Pure Gold Archived 18 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 20 March 2009

- ^ Sancilio, Cosmo (1 September 1995). "COBAT: collection and recycling spent lead/acid batteries in Italy". Journal of Power Sources. 57 (1–2): 75–80. Bibcode:1995JPS....57...75S. doi:10.1016/0378-7753(95)02246-5. ISSN 0378-7753.

- ^ "Così ho avvelenato Napoli". l'Espresso. 11 September 2008. Archived from the original on 24 September 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ "Inchiesta sui veleni a Napoli perquisiti l'Espresso e due reporter". la Repubblica. 12 September 2009. Archived from the original on 24 January 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2008.

- ^ Senior, Kathryn; Mazza, Alfredo (September 2004). "Italian "Triangle of death" linked to waste crisis". The Lancet Oncology. 5 (9): 525–527. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01561-X. ISSN 1470-2045. PMID 15384216.