South West England

South West | |

|---|---|

From top, left to right: Clifton Suspension Bridge in Bristol; the Cotswolds; Stonehenge; Newquay; Bath; Dartmoor; Torquay; Durdle Door | |

South West region shown within England | |

| Coordinates: 50°58′N 3°13′W / 50.96°N 3.22°W | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | England |

| GO established | 1994 |

| RDA established | 1998 |

| GO abolished | 2011 |

| RDA abolished | 31 March 2012 |

| Subdivisions |

27 districts

|

| Government | |

| • Type | Local authority leaders' board |

| • Body | South West Councils |

| • MPs | 55 MPs (of 650) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9,415 sq mi (24,386 km2) |

| • Land | 9,203 sq mi (23,836 km2) |

| • Rank | 1st |

| Population (2022)[3] | |

| • Total | 5,764,881 |

| • Rank | 6th |

| • Density | 630/sq mi (242/km2) |

| Ethnicity (2021) | |

| • Ethnic groups | |

| Religion (2021) | |

| • Religion | List

|

| Time zone | UTC+0 (GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

| ITL code | TLK |

| GSS code | E12000009 |

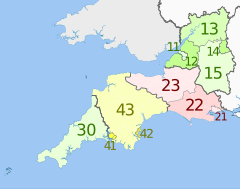

South West England, or the South West of England, is one of the nine official regions of England in the United Kingdom. It consists of the counties of Cornwall (including the Isles of Scilly), Dorset, Devon, Gloucestershire, Somerset and Wiltshire. Cities and large towns in the region include Bath, Bristol, Bournemouth, Cheltenham, Exeter, Gloucester, Plymouth and Swindon. It is geographically the largest of the nine regions of England with a land area of 9,203 square miles (23,836 km2), but the third-least populous, with an estimated 5,764,881 residents in 2022.[3]

The region includes the West Country and much of the ancient kingdom of Wessex. It includes two entire national parks, Dartmoor and Exmoor (a small part of the New Forest is also within the region); and four World Heritage Sites: Stonehenge, the Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape, the Jurassic Coast and the City of Bath. The northern part of Gloucestershire, near Chipping Campden, is as close to the Scottish border as it is to the tip of Cornwall.[5] The region has by far the longest coastline of any English region.

Following the abolition of the South West Regional Assembly in 2008 and Government Office in 2011, South West Councils provide local government coordination in the region. Bristol, South Gloucestershire, and Bath and North East Somerset are part of the West of England Combined Authority.

The region is known for its rich folklore, including the legend of King Arthur and Glastonbury Tor, as well as its traditions and customs. Cornwall has its own language, Cornish, and some regard it as a Celtic nation. The South West is known for Cheddar cheese, which originated in the Somerset village of Cheddar; Devon cream teas, crabs, Cornish pasties, and cider. It is home to the Eden Project, Aardman Animations, the Glastonbury Festival, the Bristol International Balloon Fiesta, trip hop music and Cornwall's surfing beaches. The region has also been home to some of Britain's most renowned writers, including Daphne du Maurier, Agatha Christie and Enid Blyton, all of whom set many of their works here, and the South West is also the location of Thomas Hardy's Wessex, the setting for many of his best-known novels.

Geography

[edit]| This article is part of a series within the Politics of the United Kingdom on the |

|

|---|

Geology and landscape

[edit]Most of the region is located on the South West Peninsula, between the English Channel and Bristol Channel. It has the longest coastline of all the English regions, totalling over 700 miles (1,130 km).[6] Much of the coast is now protected from further substantial development because of its environmental importance, which contributes to the region's attractiveness to tourists and residents.

Geologically the region is divided into the largely igneous and metamorphic west and sedimentary east, the dividing line slightly to the west of the River Exe.[7] Cornwall and West Devon's landscape is of rocky coastline and high moorland, notably at Bodmin Moor and Dartmoor. These are due to the granite and slate that underlie the area. The highest point of the region is High Willhays, at 2,038 feet (621 m), on Dartmoor.[8] In North Devon the slates of the west and limestones of the east meet at Exmoor National Park. The variety of rocks of similar ages seen has led to the county's name being given to that of the Devonian period.

The east of the region is characterised by wide, flat clay vales, and chalk and limestone downland. The vales, with good irrigation, are home to the region's dairy agriculture. The Blackmore Vale was Thomas Hardy's "Vale of the Little Dairies";[9] another, the Somerset Levels was created by reclaiming wetlands.[10] The Southern England Chalk Formation extends into the region, creating a series of high, sparsely populated and archaeologically rich downs, most famously Salisbury Plain, but also Cranborne Chase, the Dorset Downs and the Purbeck Hills. These downs are the principal area of arable agriculture in the region. Limestone is also found in the region, at the Cotswolds, Quantock Hills and Mendip Hills, where they support sheep farming.[11] All of the principal rock types can be seen on the Jurassic Coast of Dorset and East Devon, where they document the entire Mesozoic era from west to east.[12]

Climate

[edit]The climate of South West England is classed as oceanic (Cfb) according to the Köppen climate classification. The oceanic climate typically experiences cool winters with warmer summers and precipitation all year round, with more experienced in winter. Annual rainfall is about 1,000 millimetres (39 in) and up to 2,000 millimetres (79 in) on higher ground.[13] Summer maxima averages range from 18 °C (64 °F) to 22 °C (72 °F) and winter minimum averages range from 1 °C (34 °F) to 4 °C (39 °F) across the south-west.[13] It is the second windiest area of the United Kingdom, the majority of winds coming from the south-west and north-east.[13] Government organisations predict the region to rise in temperature and become the hottest region in the United Kingdom.[14]

Inland areas of low altitude experience the least amount of precipitation. They experience the highest summer maxima temperatures, but winter minima are colder than the coast. Snowfalls are more frequent in comparison to the coast, but less so in comparison to higher ground.[13] It experiences the lowest wind speeds and sunshine total in between that of the coast and the moors. The climate of inland areas is more noticeable the further north-east into the region.

In comparison to inland areas, the coast experiences high minimum temperatures, especially in winter, and it experiences slightly lower maximum temperatures during the summer. Rainfall is the lowest at the coast and snowfall is rarer than the rest of the region. Coastal areas are the windiest parts of the peninsula and they receive the most sunshine. The general coastal climate is more typical the further south-west into the region.

Areas of moorland inland such as: Bodmin Moor, Dartmoor and Exmoor experience lower temperatures and more precipitation than the rest of the southwest (approximately twice as much rainfall as lowland areas), because of their high altitude. Both of these factors also cause it to experience the highest levels of snowfall and the lowest levels of sunshine. Exposed areas of the moors are windier than lowlands and can be almost as windy as the coast.

Regional identity

[edit]The boundaries of the South West region are based upon those devised by central government in the 1930s for civil defence administration and subsequently used for various statistical analyses. The region is also similar to that used in the 17th-century Rule of the Major-Generals under Cromwell. (For further information, see Historical and alternative regions of England). By the 1960s, the South West region (including Dorset, which for some previous purposes had been included in a Southern region), was widely recognised for government administration and statistics. The boundaries were carried forward into the 1990s when regional administrations were formally established as Government Office Regions. A regional assembly and regional development agency were created in 1999, then abolished in 2008 and 2012 respectively.

It has been argued[by whom?] that the official South West region does not possess a cultural and historic unity or identity of itself, which has led to criticism of it as an "artificial" construct. The large area of the region, stretching as it does from the Isles of Scilly to Gloucestershire, encompasses diverse areas which have little more in common with each other than they do with other areas of England. The region has several TV stations and newspapers based in different areas, and no single acknowledged regional "capital". Many people in the region have some level of a "South West" or "West Country" regional identity, although this may not necessarily correspond to an identification with the official government-defined region. It is common for people in the region to identify at a national level (whether English, British, Cornish or a county, city or town level). Identifying as being from 'the Westcountry', amorphous though it is, tends to be more predominant further into the peninsula where the status of being from the region is less equivocal.[15][16]

In particular, Cornwall's inclusion in the region is disputed by Cornish nationalists.[17] The cross-party Cornish Constitutional Convention and Cornish nationalist party Mebyon Kernow have campaigned for a Cornish Assembly ever since the idea of regional devolution was put forward.

Settlements

[edit]The South West region is largely rural, with small towns and villages; a higher proportion of people live in such areas than in any other English region. There are two major regional cities in terms of population, which are Bristol and Plymouth (although Bristol is larger by some consideration), and two major conurbations which are the South East Dorset Conurbation (Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole) and the Bristol Metropolitan Conurbation (which includes the City of Bristol and areas of South Gloucestershire).

Cities and Towns with specific tourist and cultural sites of interest include Bath, Bristol, Salisbury, Plymouth, Exeter, Cheltenham, Gloucester and Weston-super-Mare, as well as the county of Cornwall on a widespread scale.

The region is home to six universities: University of Bristol, University of The West of England (UWE), University of Exeter, University of Plymouth, Plymouth Marjon University, University of Gloucestershire (Gloucester and Cheltenham), and Falmouth University (Cornwall).

The largest cities and towns in order of population are: Bristol (700,000) Plymouth (300,000) Bournemouth (250,000) Swindon (230,000) Poole (180,000) Gloucester (180,000) Exeter (160,000) Cheltenham (150,000) Torbay (150,000) Bath (130,000) Weston-super-Mare (80,000) Taunton (70,000) Salisbury (50,000) Weymouth (50,000).

The largest conurbations are the area sometimes called Greater Bristol, which includes parts of South Gloucestershire; and the South East Dorset conurbation, covering Bournemouth, Poole and Christchurch.

The population of the South West in 2009 was about five million.[18]

Transport

[edit]The region lies on several main line railways. The Great Western Main Line runs from London Paddington to Bristol, Exeter, Plymouth, and Penzance in the far west of Cornwall. The South West Main Line runs from London Waterloo and Southampton to Bournemouth, Poole and Weymouth in Dorset. The West of England Main Line runs from London Waterloo to Exeter via south Wiltshire, north Dorset and south Somerset. The Wessex Main Line runs from Bristol to Salisbury and on to Southampton. The Heart of Wessex Line runs from Bristol in the north of the region to Weymouth on the south Dorset coast via Westbury, Castle Cary and Yeovil, with most services starting at Gloucester.

The vast majority of trains in the region are operated by CrossCountry, Great Western Railway (GWR) and South Western Railway (SWR). GWR is the key operator for all counties in the region except Dorset where SWR is the key operator.

CrossCountry operates services to Manchester Piccadilly, Glasgow and Aberdeen. Dorset is currently the only county in the region where there are electric trains, though the Great Western Main Line and the South Wales Main Line in Wiltshire, Somerset, Greater Bristol and Gloucestershire is being electrified. SWR operate services to and from London Waterloo and serves every county in the region except Gloucestershire and Cornwall. GWR serves all counties in the region and operate to various destinations, some of which run to South Wales and the West Midlands, though almost all intercity trains operated by GWR run through the region.

Transport for Wales also operates services between Maesteg and Cheltenham Spa. West Midlands Railway operated a parliamentary train between Birmingham New Street and Gloucester via Worcester Shrub Hill, which was withdrawn in 2019 (there was once a regular service on the route, but this was withdrawn in 2009).

It has been proposed that the former London & South Western Railway Exeter to Plymouth railway be reopened to connect Cornwall and Plymouth as an alternative to the route via the Dawlish seawall that is susceptible to closure in bad weather.[19][20][21][22]

Local bus services are primarily operated by FirstGroup, Go-Ahead Group and Stagecoach subsidiaries as well as independent operators. Megabus and National Express operate long-distance services from South West England to all parts of the United Kingdom.

Three major roads enter the region from the east. The M4 motorway from London to South Wales via Bristol is the busiest. The A303 cuts through the centre of the region from Salisbury to Honiton, where it merges with the A30 to continue past Exeter to the west of Cornwall. The A31, an extension of the M27, serves Poole and Bournemouth and the Dorset coast. The M5 runs from the West Midlands through Gloucestershire, Bristol and Somerset to Exeter. The A38 serves as a western extension to Plymouth. There are three other smaller motorways in the region, all in the Bristol area.

Passenger airports in the region include Bristol, Exeter, Newquay and Bournemouth.

Within the region the local transport authorities carry out transport planning through the use of a Local Transport Plan (LTP) which outlines their strategies, policies and implementation programme.[23] The most recent LTP is that for the period 2006–11. In the South West region the following transport authorities have published their LTP online: Bournemouth U.A.,[24] Cornwall U.A.,[25] Devon,[26] Dorset,[27] Gloucestershire,[28] Plymouth U.A.,[29] Somerset,[30] Swindon U. A.,[31] Torbay U. A.[32] and Wiltshire unitary authority.[33] The transport authorities of Bath and North East Somerset U. A., Bristol U. A., North Somerset U. A. and South Gloucestershire U. A. publish a single Joint Local Transport Plan as part of the West of England Partnership.[34]

History

[edit]Pre-Roman

[edit]

There is evidence from flint artefacts in a quarry at Westbury-sub-Mendip that an ancestor of modern man, possibly Homo heidelbergensis, was present in the future Somerset from around 500,000 years ago.[35] There is some evidence of human occupation of southern England before the last ice age, such as at Kents Cavern in Devon, but largely in the south east. The British mainland was connected to the continent during the ice age and humans may have repeatedly migrated into and out of the region as the climate fluctuated. There is evidence of human habitation in the caves at Cheddar Gorge 11,000–10,000 years BC, during a partial thaw in the ice age. The earliest scientifically dated cemetery in Great Britain was found at Aveline's Hole in the Mendip Hills. The human bone fragments it contained, from about 21 different individuals, are thought to be roughly between 10,200 and 10,400 years old.[36] During this time the tundra gave way to birch forests and grassland and evidence for human settlement appears at Salisbury Plain, Wiltshire and Hengistbury Head, Dorset.

At the end of the last Ice Age the Bristol Channel was dry land, but subsequently the sea level rose, resulting in major coastal changes. The Somerset Levels were flooded, but the dry points such as Glastonbury and Brent Knoll are known to have been occupied by Mesolithic hunters.[37] The landscape at this time was tundra. Britain's oldest complete skeleton, Cheddar Man, lived at Cheddar Gorge around 7150 BC (in the Upper Palaeolithic or Old Stone Age), shortly after the end of the ice age;[38] however, it is unclear whether the region was continuously inhabited during the previous 4000 years, or if humans returned to the gorge after a final cold spell. A Palaeolithic flint tool found in West Sedgemoor is the earliest indication of human presence on the Somerset Levels.[39] During the 7th millennium BC the sea level rose and flooded the valleys, so the Mesolithic people occupied seasonal camps on the higher ground, indicated by scatters of flints.[39] The Neolithic people continued to exploit the reed swamps for their natural resources and started to construct wooden trackways. These included the Post Track and the Sweet Track. The Sweet Track, dating from the 39th century BC, is thought to be the world's oldest timber trackway and was once thought to be the world's oldest engineered roadway.[10] The Levels were also the location of the Glastonbury Lake Village as well as two lake villages at Meare.[40] Stonehenge, Avebury and Stanton Drew are perhaps the most famous Neolithic sites in the UK.

The region was heavily populated during the Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age periods. Many monuments, barrows and trackways exist. Coin evidence shows that the region was split between the Durotriges, Dobunni and Dumnonii. The Iron Age tribe in Dorset were the Durotriges, "water dwellers", whose main settlement is represented by Maiden Castle. Ptolemy stated that Bath was in the territory of the Belgae,[41] but this may be a mistake.[42] The Celtic gods were worshipped at the temple of Sulis at Bath and possibly the temple on Brean Down. Iron Age sites on the Quantock Hills include major hill forts at Dowsborough and Ruborough, as well as smaller earthwork enclosures, such as Trendle Ring, Elworthy Barrows and Plainsfield Camp.

At the time of the Roman invasion, the inhabitants of the entire area spoke a Brythonic Celtic language. Its descendant languages are still spoken to a greater or lesser extent in Cornwall, Wales, and Brittany.[43]

Roman period

[edit]

During the Roman era, the east of the region, particularly the Cotswolds and eastern Somerset, was heavily Romanised but Devon and Cornwall were much less so, though Exeter was a regional capital. There are villas, farms and temples dating from the period, including the remains at Bath.

The area of Somerset was part of the Roman Empire from AD 47 to about AD 409.[44] The empire disintegrated gradually, and elements of Romanitas lingered on for perhaps a century. In AD 47, Somerset was invaded from the south-east by the Second Legion Augusta, under the future emperor Vespasian. The hillforts of the Durotriges at Ham Hill and Cadbury Castle were captured. Ham Hill probably had a temporary Roman occupation. The massacre at Cadbury Castle seems to have been associated with the later Boudiccan Revolt of AD 60–61.[37]

The Roman invasion, and possibly the preceding period of involvement in the internal affairs of the south of England, was inspired in part by the lead mines of the Mendip Hills, which also offered the potential for the extraction of silver.[45][46] Forts were set up at Bath and Ilchester. The lead and silver mines at Charterhouse in the Mendip Hills were run by the military. The Romans established a defensive boundary along the new military road known the Fosse Way (from the Latin fossa meaning "ditch"). The Fosse Way ran through Bath, Shepton Mallet, Ilchester and south-west towards Axminster. The road from Dorchester ran through Yeovil to meet the Fosse Way at Ilchester. Salt was produced on the Somerset Levels near Highbridge and quarrying took place near Bath, named after the Roman baths.[47]

Excavations carried out before the flooding of Chew Valley Lake also uncovered Roman remains, indicating agricultural and industrial activity from the second half of the 1st century until the 3rd century AD. The finds included a moderately large villa at Chew Park,[48] where wooden writing tablets (the first in the UK) with ink writing were found. There is also evidence from the Pagans Hill Roman Temple at Chew Stoke.[48][49] In October 2001 the West Bagborough Hoard of 4th-century Roman silver was discovered in West Bagborough. The 681 coins included two denarii from the early 2nd century and 8 miliarensia and 671 siliquae all dating from AD 337 to 367. The majority were struck in the reigns of emperors Constantius II and Julian and derive from a range of mints including Arles and Lyons in France, Trier in Germany, and Rome.[50] In April 2010, the Frome Hoard, one of the largest ever hoards of Roman coins discovered in Britain, was found by a metal detectorist. The hoard of 52,500 coins dated from the 3rd century AD and was found buried in a field near Frome, in a jar 14 inches (36 cm) below the surface.[51] The coins were excavated by archaeologists from the Portable Antiquities Scheme.[52]

British kingdoms and the arrival of the Saxons

[edit]

After the Romans left at the start of the 5th century AD, the region split into several Brittonic kingdoms, including Dumnonia, centred around the old tribal territory of the Dumnonii.[53] The upper Thames area soon came under Anglo-Saxon control but the remainder of the region was in British control until the 6th century.[54][55] Bokerley Dyke, a large defensive ditch on Cranborne Chase dated to 367, delayed the Saxon conquest of Dorset, with the Romano-British remaining in Dorset for 200 years after the withdrawal of the Roman legions. The Western Wandsdyke earthwork was probably built during the 5th or 6th century. This area became the border between the Romano-British Celts and the West Saxons following the Battle of Deorham in 577.[56]

The Anglo-Saxons then gained control of the Cotswold area; but most of Somerset, Dorset and Devon (as well as Cornwall) remained in British hands until the late 7th century. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the Saxon Cenwalh achieved a breakthrough against the British Celtic tribes, with victories at Bradford-on-Avon (in the Avon Gap in the Wansdyke) in 652,[57] and further south at the Battle of Peonnum (at Penselwood) in 658,[58] followed by an advance west through the Polden Hills to the River Parrett.[59] The Saxon advance from the east seems to have been halted by battles between the British and Saxons, for example at the siege of Badon Mons Badonicus (which may have been in the Bath district, perhaps at Solsbury Hill),[60] or Bathampton Down.[61] The Battle of Bedwyn was fought in 675 between Escuin, a West Saxon nobleman who had seized the throne of Queen Saxburga, and King Wulfhere of Mercia.[62] The earliest fortification of Taunton started for King Ine of Wessex and Æthelburg, in or about the year 710. However, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle this was destroyed 12 years later.[63] Alfred the Great refortified Exeter as a defensive burh, followed by new erections at Lydford, Halwell and Pilton, although these fortifications were small compared to burhs further east, suggesting that they were protection for the elite only.

9th century and the arrival of the Danes

[edit]The English defeated a combined Cornish and Danish force at Hingston Down (near Gunnislake) in 838.[64] Edward the Elder built similarly at Barnstaple and Totnes. But sporadic Viking incursions continued until the Norman Conquest, including the disastrous defeat of the Devonians at the Battle of Pinhoe. In 876 King Alfred the Great trapped a Danish fleet at Arne and then drove it out; 120 ships were wrecked at Studland.[65] Although King Alfred had lands in Cornwall, it continued to have a British king. It is generally considered that Cornwall came fully under the dominion of the English Crown in the time of Athelstan's rule, i.e. 924–939.[66] In the absence of any specific documentation to record this event, supporters of Cornwall's English status presume that it then became part of England. However, in 944, within a mere five years of Athelstan's death, King Edmund issued a charter styling himself "King of the English and ruler of this province of the Britons". Thus we can see that then the "province" was a territorial possession, which has long claimed a special relationship to the English Crown.[67]

Corfe Castle in 978 saw the murder of King Edward the Martyr, whose body was taken first to Wareham and then to Shaftesbury. Somerset played an important part in stopping the spread of the Danes in the 9th century. Viking raids took place for instance in 987 and 997 at Watchet[68] and the Battle of Cynwit.

King Alfred was driven to seek refuge from the Danes at Athelney before defeating them in 878 at the Battle of Ethandun, usually considered to be near Edington, Wiltshire, but possibly the village of Edington in Somerset. Alfred established a series of forts and lookout posts linked by a military road, or Herepath, to allow his army to cover Viking movements at sea. The Herepath has a characteristic form which is familiar on the Quantocks: a regulation 20 m wide track between avenues of trees growing from hedge laying embankments. A peace treaty with the Danes was signed at Wedmore and the Danish king Guthrum the Old was baptised at Aller. Burhs (fortified places) had been set up by 919, such as Lyng. The Alfred Jewel, an object about 2.5-inch (64 mm) long, made of filigree gold, cloisonné-enamelled and with a rock crystal covering, was found in 1693 at Petherton Park, North Petherton.[69] This is believed to have been owned by King Alfred.[70] Monasteries and minster churches were set up all over Somerset, with daughter churches of the minsters in manors. There was a royal palace at Cheddar, which was used at times in the 10th century to host the Witenagemot.[71]

11th century

[edit]In the late pre-Norman period, the east coast of modern-day England came under the growing sway of the Norsemen. Eventually England came to be ruled by Norse monarchs, and the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms fell one by one, Wessex being conquered in 1013 by King Sweyn Forkbeard.[72][73][74] Sweyn's realms included Denmark and Norway, and parts of England such as Mercia (an Anglian kingdom roughly coinciding with the English Midlands), much of which, along with northern England, fell under the Danelaw. Sweyn ruled Wessex, along with his other realms, from 1013 onwards, followed by his son Canute the Great. But Cornwall was not part of his realm of Wessex. A map by the American historian called "The Dominions of Canute" (pictured just above) shows that Cornwall, like Wales and Scotland, was part neither of Sweyn Forkbeard's nor of Canute's Danish empire. Neither Sweyn Forkbeard nor Canute conquered or controlled Scotland, Wales or Cornwall; but these areas were "client nations": subject to payment of a yearly tribute or danegeld to Sweyn and later Canute, all three areas retained their autonomy from the Danes. Ultimately, the Danes lost control of Wessex in 1042 on the death of both of Canute's sons. Edward the Confessor retook Wessex for the Saxons.[75] In 1016 Edmund Ironside was crowned king at Glastonbury.[76]

Middle Ages

[edit]

After the Norman Conquest the region was controlled by various Norman as well as Breton lords and later by local gentry, a few of whom appear to have been descended from pre-Conquest families. In 1140, during the civil war of King Stephen's reign, the castles of Plympton and Exeter were held against the king by Baldwin de Redvers and this gave rise to the defensive castles at Corfe Castle, Powerstock, Wareham and Shaftesbury. The period saw the growth of towns such as Truro, Totnes, Okehampton and Plympton in the west of the region, but these were small compared with the established wealth of ancient cathedral cities in the east of the region such as Exeter, Bath and Wells. Wealth grew from sheep farming in the east of the region: church controlled estates such as Glastonbury Abbey and Wells became among the richest in England, while tin and silver mining was important in Devon and Cornwall; Stannary Parliaments with semi-autonomous powers were established. Farming prospered until it was severely hit by the Black Death which arrived in Dorset in 1348 and quickly spread through Somerset, causing widespread death, with mortality rates perhaps as high as 50% in places. The resulting labour shortage led to changes in feudal practices. Crafts and industries also flourished; the Somerset woollen industry was then one of the largest in England.[77] Coal mining in the Mendips was an important source of wealth while quarrying also took place.

Many parish churches were rebuilt in this period. Between 1107 and 1129 William Giffard, the Chancellor of King Henry I, converted the bishop's hall in Taunton into Taunton Castle. It passed to the king in 1233[78] and in 1245 repairs were ordered to its motte and towers. During the 11th-century Second Barons' War against Henry III, Bridgwater was held by the barons against the King. During the Middle Ages sheep farming for the wool trade came to dominate the economy of Exmoor. The wool was spun into thread on isolated farms and collected by merchants to be woven, fulled, dyed and finished in thriving towns such as Dunster. The land started to be enclosed and from the 17th century onwards larger estates developed, leading to establishment of areas of large regular shaped fields. During this period a royal forest and hunting ground was established, administered by the Warden. The royal forest was sold off in 1818.[79]

Where conditions were suitable, coastal villages and ports had an economy based on fishing. The larger ports such as Fowey contributed vessels to the naval enterprises of the King and were subject to attack from the French in return. Bridgwater was part of the Port of Bristol until the Port of Bridgwater was created in 1348,[68] covering 80 miles (130 km) of the Somerset coast line, from the Devon border to the mouth of the River Axe.[80][81] Historically, the main port on the river was at Bridgwater; the river being bridged at this point, with the first bridge being constructed in 1200.[82] Quays were built in 1424; with another quay, the Langport slip, being built in 1488 upstream of the Town Bridge.[83] In Bristol the port began to develop in the 11th century.[84] By the 12th century Bristol was an important port, handling much of England's trade with Ireland. During this period Bristol also became a centre of shipbuilding and manufacturing. Bristol was the starting point for many important voyages, notably John Cabot's 1497 voyage of exploration to North America.[85] By the 14th century Bristol was one of England's three largest medieval towns after London, along with York and Norwich, with perhaps 15,000–20,000 inhabitants on the eve of the Black Death of 1348–49.[86] The plague resulted in a prolonged pause in the growth of Bristol's population, with numbers remaining at 10,000–12,000 through most of the 15th and 16th centuries.[87]

During the Wars of the Roses, there were frequent skirmishes between the Lancastrian Thomas Courtenay, Earl of Devon and Yorkist William, Lord Bonville. In 1470, Edward IV pursued Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick and George, Duke of Clarence as far as Exeter after the Battle of Lose-coat Field. The organisation of the region remained based on the shires and Church estates, which were largely unchanged throughout the period. Some of the most important nobles in the South West included the Courtenays Earl of Devon, William Bonville, 1st Baron Bonville, and Humphrey Stafford, earl of Devon whose wider influence stretched from Cornwall to Wiltshire. After 1485, the Earl of Devon, Henry VII's chamberlain, Giles Daubeney, 1st Baron Daubeney and Robert Willoughby, 1st Baron Willoughby de Broke were also influential.[88] In 1497, early in Henry VII's reign, the royal pretender Perkin Warbeck, besieged Exeter. The Cornish Rebellion of 1497 led by An Gof and Thomas Flamank ended in a march to Blackheath in London where the Cornish forces were massacred.

16th century

[edit]Great disturbances throughout both Cornwall and Devon followed the introduction of Edward VI's Book of Common Prayer. The day after Whit Sunday 1549, a priest at Sampford Courtenay was persuaded to read the old mass.[89] This insubordination spread swiftly into serious revolt. The Cornish quickly joined the men of Devon in the Prayer Book Rebellion and Exeter was besieged until relieved by Lord Russell.[90] The Cornish had a particular motivation for opposing the new English language prayer book, as there were still many monoglot Cornish speakers in West Cornwall. The Cornish language declined rapidly afterwards and the Dissolution of the Monasteries resulted in the eventual loss of the Cornish language as a primary language. By the end of the 18th century it was no longer a first language.

The Council of the West was a short-lived administrative body established by Henry VIII for the government of the western counties of England. It was analogous in form to the Council of the North. The council was established in March 1539, with Lord Russell as its Lord President. Members included Thomas Derby, Sir Piers Edgcumbe, Sir Richard Pollard and John Rowe. However, the fall of Thomas Cromwell, the chief political supporter of government by Councils, and the tranquillity of the western counties made it largely superfluous. It last sat in summer 1540, although it was never formally abolished.[91]

17th century

[edit]The Bristol Channel floods of 1607 are believed to have affected large parts of the Somerset Levels, with flooding up to 8 feet (2 m) above sea level.[92][93] In 1625, a House of Correction was established in Shepton Mallet, and when it closed HMP Shepton Mallet was England's oldest prison still in use.[94][95]

During the English Civil War, Somerset was largely Parliamentarian, although Dunster was a Royalist stronghold. The county saw important battles between the Royalists and the Parliamentarians, notably at Lansdowne in 1643 and Langport in 1645.[96] Bristol was occupied by Royalist military, after they overran Royal Fort, the last Parliamentarian stronghold in the city.[87] Taunton Castle had fallen into ruin by 1600 but it was repaired during the Civil War. The castle changed hands several times during 1642–45 along with the town.[97] During the Siege of Taunton it was defended by Robert Blake, from July 1644 to July 1645. After the war, in 1662, the keep was demolished and only the base remains. This war resulted in castles being slighted (destroyed to prevent their re-use).[98]

In 1685, the Duke of Monmouth led the Monmouth Rebellion in which a force partly raised in Somerset fought against James II. The rebels landed at Lyme Regis and travelled north hoping to capture Bristol and Bath, Puritan soldiers damaged the west front of Wells Cathedral, tore lead from the roof to make bullets, broke the windows, smashed the organ and the furnishings, and for a time stabled their horses in the nave.[99] They were defeated in the Battle of Sedgemoor at Westonzoyland, the last battle fought on English soil.[100] The Bloody Assizes which followed saw the losers being sentenced to death or transportation.[101] At the time of the Glorious Revolution, King James II gathered his main forces, altogether about 19,000 men, at Salisbury, James himself arriving there on 19 November 1688. The first blood was shed at the Wincanton Skirmish in Somerset. In Salisbury, James heard that some of his officers, such as Edward Hyde, had deserted, and he broke out in a nose-bleed which he took as a bad omen. His commander in chief, the Earl of Feversham, advised retreat on 23 November, and the next day John Churchill deserted to William. On 26 November, James's daughter Princess Anne did the same, and James returned to London the same day, never again to be at the head of a serious military force in England.[102]

Modern history

[edit]Since 1650, the City of Plymouth has grown to become the largest city in Devon, mainly due to the naval base at Devonport. Her Majesty's Naval Base (HMNB) Devonport is one of three operating bases in the United Kingdom for the Royal Navy. HMNB Devonport is now the largest naval base in Western Europe.[103] The large Portland Harbour, built at the end of the 19th century and protected by Nothe Fort and the Verne Citadel, was for many years, including during the wars, another of the largest Royal Navy bases.

The 19th century saw improvements to roads in the region with the introduction of turnpikes and the building of canals and railways. The usefulness of the canals was short-lived, though they have now been restored for recreation. Chard claims to be the birthplace of powered flight, in 1848 when the Victorian aeronautical pioneer John Stringfellow first demonstrated that engine-powered flight was possible through his work on the Aerial Steam Carriage.[104][105] North Petherton was the first town in England (and one of the few ever) to be lit by acetylene gas lighting.[106]

Around the 1860s, at the height of the iron and steel era, a pier and a deep-water dock were built, at Portishead to accommodate the large ships that had difficulty in reaching Bristol Harbour.[107][108] The Portishead power stations were coal-fed power stations built next to the dock. Industrial activities ceased in the dock with the closure of the power stations. The Port of Bristol Authority finally closed the dock in 1992,[109] and it has now been developed into a marina and residential area.

During the First World War many soldiers from the South West were killed, and war memorials were put up in most of the towns and villages; only a few villages escaped casualties. There were also casualties – though much fewer – during the Second World War, who were added to the memorials. Several areas were bases for troops preparing for the 1944 D-Day landings. Exercise Tiger, or Operation Tiger, was the code names for a full-scale rehearsal in 1944 for the D-Day invasion of Normandy. The British Government evacuated approximately 3,000 local residents in the area of Slapton, now South Hams District of Devon.[110] Some of them had never left their villages before.[111] Bristol's city centre suffered severe damage from Luftwaffe bombing during the Bristol Blitz of World War II.[112] The Royal Ordnance Factory ROF Bridgwater was constructed early in World War II for the Ministry of Supply.[113] The Taunton Stop Line was set up to resist a potential German invasion, and the remains of its pill boxes can still be seen, as well as others along the coast.[114]

Exmoor was one of the first British National Parks, designated in 1954, under the 1949 National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act.[115] and is named after its main river. It was expanded in 1991 and in 1993 Exmoor was designated as an Environmentally Sensitive Area. The Quantock Hills were designated as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) in 1956, the first such designation in England under the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. The Mendip Hills followed with AONB designation in 1972.[116]

World War II

[edit]

Much of the Battle of the Beams was carried out at the Telecommunications Research Establishment at Worth Matravers in Dorset; the H2S radar was developed by Sir Bernard Lovell of Bristol. The Gloster Meteor at Newquay Air Museum is the oldest flying jet aircraft in the world. Long Ashton Research Station in Somerset invented Ribena (for population health in World War II) and improved cider.

Scientific heritage

[edit]William Herschel, previously a clarinet player, of Bath discovered infrared radiation on 11 February 1800, and the planet Uranus in March 1781; he had made important improvements to the reflecting telescope by increasing the mirror diameter. Herschel then built a 20-ft reflecting telescope and invented the star count, working out that the Milky Way is a disc, which he called a grindstone, and that it is a galaxy. Sir Arthur C. Clarke of Minehead invented the idea of artificial satellites; he sent a letter to Harry Wexler who then developed the first weather satellite TIROS-1. Sir Arthur Eddington of Weston-super-Mare was the first to realise that nuclear fusion powered the Sun; at the 1920 British Association meeting he said that the Sun converted hydrogen into helium, although the mechanism was not known until 1933. James Bradley was an important astronomer from Gloucestershire, who discovered the aberration of light.

Jan Ingenhousz, the Dutch biologist, discovered photosynthesis in 1779 at Bowood House in Wiltshire; on 1 August 1774, Joseph Priestley discovered oxygen there too. A fossil of the oldest ancestor of the Tyrannosaurus was found in Gloucestershire; Mary Anning was a famous fossil collector from Lyme Regis. Edward Jenner, pioneer of vaccination, was from Gloucestershire.

Industrial heritage

[edit]Sir Benjamin Baker from Cheltenham jointly-designed the 1890 Forth Bridge. William Murdoch in 1792 lit his house in Redruth with gas, the first in Britain. Plasticine was invented 1897 in Bath by William Harbutt. Thomas Young of Somerset is known for his double-slit experiment in optics, and in solid mechanics for his famous Young's modulus. Henry Fox Talbot, inventor of a negative-positive process in 1841, from Wiltshire made the first photograph in August 1835; Nicéphore Niépce of France can claim the first photo in 1826; William Friese-Greene of Bristol is thought to be the father of cinematography after inventing his chronophotographic camera in 1889.

Hinkley Point A nuclear power station was a Magnox power station constructed between 1957 and 1962 and operating until ceasing generation in 2000.[117] Hinkley Point B is an Advanced Gas-cooled Reactor (AGR) which was designed to generate 1250 MW of electricity (MWe). Construction of Hinkley Point B started in 1967. In September 2008 it was announced, by Électricité de France (EDF), that a third, twin-unit European Pressurised Reactor (EPR) power station known as Hinkley Point C is planned,[118] to replace Hinkley Point B which was due for closure in 2016,[119] now extended until 2022. In 1989 the Berkeley nuclear power station was the first in the UK to be decommissioned. The steam-generating heavy water reactor was developed at Winfrith in Dorset.

Ted Codd, inventor of databases and SQL, was from Poole. Campden BRI at Ebrington in north-east Gloucestershire was an important research centre for canned food; J. S. Fry & Sons of Bristol made world's first chocolate bar in 1847.

The first carpets were made in Britain in 1741 at Wilton, Wiltshire. In 1698, Thomas Savery of Devon developed an early steam engine; Thomas Newcomen from Dartmouth made another early steam engine in 1710. Edward Butler, a farmer from Devon born in Bickington in 1862, invented the petrol engine.

Demographics

[edit]

At the 2021 census, the population of the South West region was 5,701,186 [120]

It has long been one of the fastest-growing regions in England and its 2021 population had increased by 7.8% since 2011 (when it was 5,288,935), and by 15.7% over the 2001 figure (4,928,434).

At the 2021 census, the proportion of white people in the region decreased from 95.4% to 93.1%, while the proportion of black and Asian residents increased significantly. At that time, 87.8% of the region's residents were classed as White British, which was higher than the England average of 73.5%.[120]

The region had the oldest median age in England; in the 2011 census, West Somerset had the UK's oldest average age – almost 48. The region had the second-highest proportion (23%) of rural population in the UK, after Northern Ireland.

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1801 | 1,355,811 | — |

| 1811 | 1,498,569 | +1.01% |

| 1821 | 1,754,725 | +1.59% |

| 1831 | 1,981,488 | +1.22% |

| 1841 | 2,173,157 | +0.93% |

| 1851 | 2,263,070 | +0.41% |

| 1861 | 2,319,593 | +0.25% |

| 1881 | 2,444,167 | +0.26% |

| 1891 | 2,543,186 | +0.40% |

| 1911 | 2,825,046 | +0.53% |

| 1921 | 2,877,866 | +0.19% |

| 1931 | 2,989,977 | +0.38% |

| 1951 | 3,483,675 | +0.77% |

| 1961 | 3,693,029 | +0.59% |

| 1971 | 4,132,770 | +1.13% |

| 1981 | 4,163,729 | +0.07% |

| 1991 | 4,610,241 | +1.02% |

| 2001 | 4,928,364 | +0.67% |

| 2011 | 5,288,935 | +0.71% |

| 2021 | 5,701,186 | +0.75% |

| Source: A Vision of Britain through Time[121] | ||

Ethnicity

[edit]| Ethnic group | Year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991[122] | 2001[123] | 2011[124] | 2021[120] | |||||

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| White: Total | 4,546,848 | 98.6% | 4,815,316 | 97.7% | 5,046,429 | 95.41% | 5,309,608 | 93.1% |

| White: British | – | – | 4,701,602 | 95.39% | 4,855,676 | 91.8% | 5,008,149 | 87.8% |

| White: Irish | – | – | 32,484 | 0.65% | 28,616 | 0.54% | 31,698 | 0.6% |

| White: Irish Traveller/Gypsy | – | – | – | – | 5,631 | 6,382 | 0.1% | |

| White: Roma | – | – | – | – | – | – | 5,785 | 0.1% |

| White: Other | – | – | 81,230 | 1.64% | 156,506 | 2.95% | 257,594 | 4.5% |

| Asian or Asian British: Total | 28,368 | 0.6% | 45,522 | 0.92% | 105,537 | 1.99% | 159,184 | 2.8% |

| Asian or Asian British: Indian | 10,915 | 16,394 | 34,188 | 58,847 | 1.0% | |||

| Asian or Asian British: Pakistani | 3,925 | 6,729 | 11,622 | 17,432 | 0.3% | |||

| Asian or Asian British: Bangladeshi | 2,308 | 4,816 | 8,416 | 12,217 | 0.2% | |||

| Asian or Asian British: Chinese | 6,687 | 12,722 | 22,243 | 26,516 | 0.5% | |||

| Asian or Asian British: Asian Other | 4,533 | 4,861 | 29,068 | 44,172 | 0.8% | |||

| Black or Black British: Total | 21,779 | 0.5% | 20,920 | 0.42% | 49,476 | 0.93% | 69,614 | 1.3% |

| Black or Black British: African | 2,820 | 6,171 | 24,226 | 43,318 | 0.8% | |||

| Black or Black British: Caribbean | 12,387 | 12,405 | 15,129 | 17,226 | 0.3% | |||

| Black or Black British: Other | 6,572 | 2,344 | 10,121 | 9,070 | 0.2% | |||

| Mixed: Total | – | – | 37,371 | 0.75% | 71,884 | 1.35% | 114,074 | 2% |

| Mixed: White and Caribbean | – | – | 13,343 | 25,669 | 33,217 | 0.6% | ||

| Mixed: White and African | – | – | 3,917 | 8,550 | 15,644 | 0.3% | ||

| Mixed: White and Asian | – | – | 11,198 | 21,410 | 34,960 | 0.6% | ||

| Mixed: Other Mixed | – | – | 8,913 | 16,255 | 30,253 | 0.5% | ||

| Other: Total | 12,429 | 0.3% | 9,305 | 0.18% | 15,609 | 0.29% | 48,706 | 0.9% |

| Other: Arab | – | – | – | – | 5,692 | 10,302 | 0.2% | |

| Other: Any other ethnic group | 12,429 | 0.3% | 9,305 | 0.18% | 9,917 | 38,404 | 0.7% | |

| Ethnic minority: Total | 62,576 | 1.4% | 113,118 | 2.3% | 242,506 | 4.6% | 391,578 | 6.9% |

| Total | 4,609,424 | 100% | 4,928,434 | 100% | 5,288,935 | 100% | 5,701,186 | 100% |

Religion

[edit]| Religion | 2021[125] | 2011[126] | 2001[127] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Christianity | 2,635,872 | 46.2% | 3,194,066 | 60.4% | 3,646,488 | 74.0% |

| Islam | 80,152 | 1.4% | 51,228 | 1.0% | 23,465 | 0.5% |

| Hinduism | 27,746 | 0.5% | 16,324 | 0.3% | 8,288 | 0.2% |

| Buddhism | 24,579 | 0.4% | 19,730 | 0.4% | 11,299 | 0.2% |

| Sikhism | 7,465 | 0.1% | 5,892 | 0.1% | 4,614 | 0.1% |

| Judaism | 7,387 | 0.1% | 6,365 | 0.1% | 6,747 | 0.1% |

| Other religion | 36,884 | 0.6% | 29,279 | 0.6% | 18,221 | 0.4% |

| No religion | 2,513,369 | 44.1% | 1,549,201 | 29.3% | 825,461 | 16.7% |

| Religion not stated | 367,732 | 6.5% | 416,850 | 7.9% | 383,851 | 7.8% |

| Total population | 5,701,186 | 100% | 5,288,935 | 100% | 4,928,434 | 100% |

Housing

[edit]35% of people in the region own their homes outright, with no debt, the highest in the UK. The Cotswold district had the biggest house price increases in the region, and the second-biggest in the UK outside of London and the South-East, in a March 2015 survey. Weymouth and Portland has the highest council tax in England. West Somerset has the lowest average full-time pay at £287; West Somerset is also the district where poor children do much worse than wealthier children at school, with some of the worst differences in the UK, according to Ambition School Leadership.

Teenage pregnancy

[edit]For top-tier authorities, Torbay has the highest teenage pregnancy rate in the region,[128] with Exeter the highest rate for council districts. For top-tier authorities, North Somerset (closely followed by Bath & NE Somerset) has the lowest rate, with Cotswold having the lowest rate for council districts.

Health

[edit]The population in the region with the highest obesity level is Sedgemoor in Somerset, with 73.4%, the fifth in the UK.[citation needed] North Dorset has the lowest proportion of cancer deaths in England – 97 per 100,000 (the England average is 142 per 100,000), down from 162 ten years earlier.[when?]

In the 2011 census, East Dorset had the highest rate of marriage in the UK; East Dorset also has the third-highest life expectancy for men in the UK at 82.7.[citation needed]

Crime

[edit]For England and Wales in 2015, Wiltshire has the fourth-lowest crime rate, and Devon and Cornwall has the fifth-lowest.

Deprivation

[edit]As measured by the English Indices of Deprivation 2007, the region shows similarities with Southern England in having more Lower Layer Super Output Areas in the 20% least multiple deprived districts than the 20% most deprived.[129] The relative amount of deprivation is similar to the East Midlands, except the South West has many fewer deprived areas. According to the LSOA data in 2007, the most deprived districts[130] (before Cornwall became a unitary authority) were, in descending order: Bristol (64th in England), Torbay (71st), Plymouth (77th), Kerrier (86th), Restormel (89th), North Cornwall (96th), and West Somerset (106th). At county level, the deprived areas are City of Bristol (49th in England), Torbay (55th), Plymouth (58th), and Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly (69th).

The least deprived council districts are, in descending order: East Dorset, North Wiltshire, South Gloucestershire, Cotswold, Kennet, Stroud, Tewkesbury, West Wiltshire, Salisbury, and Bath and North East Somerset. At county level, the least deprived areas, in descending order, are South Gloucestershire, Wiltshire, Bath and North East Somerset, Dorset, Gloucestershire, Poole, North Somerset, and Somerset. For smaller areas, the least-deprived in the region are E01015563 (139th in England) – Shaw and Nine Elms ward, in north Swindon; E01014791 (163rd in England) – Portishead East ward, in North Somerset off the A369 in Portishead and North Weston; E01020377 (184th in England) – Colehill East ward, in East Dorset, east of Wimborne Minster.

In March 2011, the region had the second-lowest unemployment claimant count in England, second to South East England, with 2.7%. Inside the region, Torbay has the highest rate with 4.5%, followed by Bristol and Plymouth with 3.8%. East Dorset has the lowest rate with 1.4%.[131]

Language

[edit]The Cornish language evolved from the Southwestern dialect of the Brittonic language spoken during the Iron Age and Roman period.[132] The area controlled by the Britons was progressively reduced by the expansion of Wessex after the 6th century, and in 936 Athelstan set the east bank of the Tamar as the boundary between Anglo-Saxon Wessex and Celtic Cornwall.[133] The Cornish language continued to flourish during the Middle Ages but declined thereafter, and the last speaker of traditional Cornish died in the 19th century.[134] Geographical names derived from the British language are widespread in South West England, and include several examples of the River Avon, from abonā = "river" (cf. Welsh afon), and the words "tor" and "combe".[135]

Until the 19th century, the West Country and its dialects of the English language were largely protected from outside influences, due to its relative geographical isolation. The West Country dialects derive not from a corrupted form of modern English, but from the Southwestern dialects of Middle English, which themselves derived from the dialects of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex. Late West Saxon, which formed the earliest English language standard, from the time of King Alfred until the late 11th century, is the form in which the majority of Anglo-Saxon texts are preserved. Thomas Spencer Baynes claimed in 1856 that, due to its position at the heart of the Kingdom of Wessex, the relics of Anglo-Saxon accent, idiom and vocabulary were best preserved in the Somerset dialect. There is some influence from the Welsh and Cornish languages, depending on the specific location.

West Country dialects are commonly represented as "Mummerset", a kind of catchall southern rural accent invented for broadcasting.

Economy and industry

[edit]

The most economically productive areas within the region are Bristol, the M4 corridor and south east Dorset, which are the areas with the best links to London. Bristol alone accounts for a quarter of the region's economy, with the surrounding areas of Gloucestershire, Somerset and Wiltshire accounting for a further quarter.[136]

Bristol's economy has been built on maritime trade, including the import of tobacco and the slave trade. Since the early 20th century, however, aeronautics have taken over as the basis of Bristol's economy, with companies including Airbus UK, Rolls-Royce (military division) and BAE Systems (former Bristol Aeroplane Company then BAC) manufacturing in Filton. Defence Equipment & Support is at MoD Abbey Wood. More recently defence, telecommunications, information technology and electronics have been important industries in Bristol, Swindon and elsewhere. The Driver & Vehicle Standards Agency, the Soil Association, Clerical Medical, and Bristol Water are in Bristol; Indesit makes tumble dryers in Yate; HP and Infineon Technologies UK are at Stoke Gifford. Knorr-Bremse UK make air brakes in Emersons Green. The South West Observatory's Economy Module provides a detailed analysis of the region's economy.[137]

The region's Gross value added (GVA) breaks down as 69.9% service industry, 28.1% production industry and 2.0% agriculture. This is a slightly higher proportion in production, and lower proportion in services, than the UK average. Agriculture, though in decline, is important in many parts of the region. Dairy farming is especially important in Dorset and Devon, and the region has 1.76 million cattle, second to only one other UK region, and 3,520 square miles (9,117 km2) of grassland, more than any other region. Only 5.6% of the region's agriculture is arable.[136]

Tourism is important in the region, and in 2003 the tourist sector contributed £4,928 million to the region's economy.[138] In 2001 the GVA of the hotel industry was £2,200 million, and the region had 13,800 hotels with 250,000 bed spaces.[136]

There are large differences in prosperity between the eastern parts of the region and the west. While Bristol is the second most affluent large city in England after London,[139] parts of Cornwall have among the lowest average incomes in Northern Europe.

The region's Manufacturing Advisory Service is on the A38 north of Gloucester at Twigworth,[140] and the UK Trade & Investment office is at the Leigh Court Business Centre in Abbots Leigh, North Somerset.[141]

Cornwall

[edit]

Major companies in Cornwall include Imerys who are major producers of kaolin. Rodda's make clotted cream near Scorrier, off the A30 east of Redruth. Fugro Seacore in Mongleath near Falmouth are leading offshore drilling contractors; Pendennis makes luxury yachts at Falmouth Docks. Kensa Heat Pumps are west of Truro. Cornish Country Larder, owned by Arla, make cheese (Cornish Brie) at Trevarrian on the B3276 in Mawgan-in-Pydar, north of Newquay Airport (former RAF St Mawgan).

Allen & Heath make mixing consoles in Penryn. Fourth Element (wet suits) are on the A3083 at Cury, south of RNAS Culdrose and Helston. A.P. Valves make diving equipment in Helston off the B3297 on Water-Ma-Trout Ind Estate, next to Helston Community College; Spiral Construction is the UK's leading manufacturer of spiral staircases.

Gul (clothing) (watersports clothing) are on Callywith Gate Ind Est in Cooksland Bodmin at the western end of the A38, on the north end of the Bodmin bypass; C-Skins (wetsuits) are on the Walker Lines Ind Est, south of Bodmin on the B3268; Fitzgerald Lighting are west of the Carminow Cross junction. GCHQ Bude is an important radar station in Morwenstow. On the other side of the river from Devonport is HMS Raleigh, off the A374 at Torpoint, home of the Royal Navy Submarine School (moved from HMS Dolphin in Gosport in 1999) and its Submarine Command Course; it provides all the training for the Royal Naval Reserve (RNR).

Cornwall has become reliant on tourism, more so than the other counties of the South West. In 2010 Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly had the lowest GVA per head of any county or unitary authority in England.[142] It contributes only 7.4% of the region's economy[143] and has received EU Convergence funding (formerly Objective One funding) since 2000.[144] Over four million people visit the county each year.[145] The reasons for Cornwall's poor economic performance are complex and apparently persistent, but causes include its remoteness and poor transport links,[136] the decline of its traditional industries, such as mining, agriculture and fishing, the low-wealth generating capacity of tourism, relocation of higher skilled jobs to other parts of the South West, and lack of a concerted economic strategy (although use of European Regional Development Fund and European Social Fund monies have been deployed in an attempt at restructuring).[146]

Devon

[edit]

The Met Office is in Exeter, as are Pennon Group, the water company, Pedigree Dolls & Toys (Sindy doll), and Thrifty Car Rental UK, which is at Ashton Business Centre in St Thomas on the A377 opposite the Exeter Retail Park. The airline Flybe was based at Exeter Airport until 2019; Plymouth City Airport closed in 2011. Chatham Marine clothing and footwear is off the B3123 on the Marsh Barton Trading Estate, near Alphington. Eclipse Internet and EDF Energy are in the same building south-east of the Met Office next to the M5; Stovax Group, who make wood and gas-burning stoves, are further south on Sowton Ind Est next to Alcoa Howmet UK, who make vacuum alloy airfoil castings for industrial gas turbines. DEFRA have a main site for Devon at Winslade Park, to the east at Clyst St Mary; nearby to the south on the A376 is the HQ of Devon & Somerset Fire & Rescue Service. Dormakaba UK, at Tiverton, are a world-leader in turnstiles, revolving doors and locks; Heathcoat Fabrics make the DecelAir fabric for parachutes. Taw Valley cheese is made by Arla Foods UK (former Milk Link) at North Tawton off the A3124, also the HQ of Gregory Distribution.

XYZ Machine Tools is off the A38 close to the M5 bridge in Burlescombe near the Somerset boundary. The Donkey Sanctuary is in Sidmouth. Axminster Carpets makes carpets for every Wetherspoons pub.[citation needed]

Appledore Shipbuilders are based at Appledore, Torridge, Devon, three miles north of Bideford, who built sections of the Queen Elizabeth-class aircraft carriers. Parker Hannifin have their instrumentation division next to the Taw Bridge (A361) at Pottington in Barnstaple; CQC makes personal equipment and Osprey body armour; off the A361 towards Barnstaple, is a chipboard (Conti and Caberboard) plant of Norbord. Next to Royal Marines Base Chivenor, Perrigo makes Germolene and own-label OTC medicines at the Wrafton Laboratories in Heanton Punchardon on the A361. Actavis UK (former Cox Pharmaceuticals, part of Hoechst AG), off the A361 east of Barnstaple, make levothyroxine and other thyroid hormones. Dartington Crystal in Torrington makes Royal Brierley. Pall Europe make filtration products in Ilfracombe.

All Ambrosia (former Unilever) products are made at the Ambrosia Creamery in Lifton, off the A30 on the River Lyd. Parkham Farms make Westcountry Farmhouse Cheddar at Woolfardisworthy, Torridge. SC Group (Supacat) at Dunkeswell Aerodrome, north of Honiton, make protective vehicles for the Army, notably the Jackal; these vehicles are also made in Plymouth by Babcock International formerly Devonport Management Limited (DML); Oceanic Worldwide UK makes scuba diving gear. Quested make high-end loudspeakers on Heathpark Ind Est, west of Honiton, next to the railway.

Centrax make industrial gas turbines in Newton Abbot; to the north-west, on the A38 at the A382 junction at Heathfield in Bovey Tracey, British Ceramic Tile have the largest ceramic tile plant in Europe. Suttons Seeds is in Paignton; AVX, off the A3022, was a worldwide site for tantalum capacitors, until the company moved production to the Czech Republic in 2009. Britannia Royal Naval College is at Dartmouth.

HMNB Devonport (HMS Drake, the largest naval base in western Europe) is in Plymouth. Toshiba had a large presence in Ernesettle, in the north of Plymouth, which was the second-largest employer after the Royal Navy, until they moved production of televisions to Kobierzyce in Poland in 2009; it made its last television at the site on 27 August 2009; Vispring (beds) is next to Kawasaki Precision Machinery. Snowbee make fishing tackle. 3 Commando Brigade is at Stonehouse Barracks. The Range (home and leisure) is on the B3432 in Estover east of Plymouth Airport; opposite is Fine Tubes and further east Barden make ball-bearings for the aerospace industry; on the furthest east of the industrial estate is Wrigley Company UK; its Extra brand is the second best-selling confectionery in the UK after Dairy Milk.[citation needed]

X-Fab UK (semiconductor fabrication plant, former Plessey Semiconductors) is next to the A386 Bickleigh Cross roundabout; nearby BD have a large plant making medical vacutainers (for blood samples) on Belliver Way Ind Est in the north of Plymouth; south of BD off the B3373 in Southway is Silicon Sensing Systems (who make vibrating structure gyroscopes and are owned by UTC Aerospace Systems, previously BAE Systems, and BAe Dynamics, who had made nose cones for aircraft including Concorde), and Schneider Electric UK (Drayton Controls, market-leading thermostatic radiator valves for central heating, previously owned by Invensys Controls UK).

Hemerdon Mine, east of Plymouth, has one of the largest deposits of tungsten in the world. Wills Marine make motor inflatable boats off the A379 in Kingsbridge.[citation needed]

Dorset

[edit]New Look is in Weymouth; it is Britain's second-biggest value clothing retailer, with over 800 stores in 21 countries. Wytch Farm (BP) is the UK's largest onshore oil field. Meggitt is a leading aerospace and defence contractor, based west of Bournemouth Airport, with Hobbycraft, at a former BAC works in Hurn, close to West Parley. The Royal Armoured Corps is based at Bovington Camp, and next door is the Bovington Tank Museum; the Army has three armoured regiments (Royal Dragoon Guards, Royal Tank Regiment and King's Royal Hussars) and 227 FV4034 70-tonne Challenger 2 tanks; Germany has around 1,000 tanks and Russia has 3,300. Westwind Air Bearings (owned by Novanta) is off the A352 at Wareham St Martin, west of Poole, near Holton Heath railway station, with Mathmos (lighting), founded by Edward Craven Walker who invented the lava lamp.

Tata Consultancy Services (former Unisys Insurance Services before 2010) is in Bournemouth. Imagine Publishing, a magazine publisher, with The Mortgage Works (owned by Nationwide Building Society), is at the A35/A347 Richmond Hill Roundabout; Organix is in the centre; McCarthy & Stone, who make much of Britain's retirement housing, is on the B3066. LV= (insurance) is at Frizzell House at Westbourne at the County Gates Gyratory A35/A338 roundabout. JPMorgan Chase have their large Chaseside site at the A3060/A338 junction opposite the Royal Bournemouth Hospital, RIAS (insurance) and Teachers Assurance, towards Holdenhurst.

Merlin Entertainments (who own Sea Life Centres, and are the world's second largest theme park operator after Disney) is in Poole with a former division, Aquarium Technology, at the end of the A350 near the Twin Sails bridge. Ryvita is made in Parkstone on the B3061. Fitness First, the largest privately owned health club group in the world, originated in Bournemouth and is now globally headquartered south of Fleet's Corner. Siemens Traffic Controls make most of the UK's traffic lights west near Fleet's Corner; the main traffic light in the UK is the Siemens Helios (the other make is the Peek Elite). North of Fleets Lane, south of the Wessex Gate Retail Park, is Parvalux, on the A3049 on the West Howe Ind Estate in Wallisdown, which makes geared DC electric motors and gearboxes; further south is Faerch Plast (former Sealed Air, which makes trays for food) then Fitness First, and Aeronautical & General Instruments; further north is Lush, the cosmetics company, with Hamworthy Wärtsilä (Finnish), and Hamworthy Combustion (owned by Koch Industries), at the A349/A3049 junction in Fleetsbridge, is an international engineering consultancy.

Sunseeker International is a main motor yacht manufacturer; it made the boat in the opening sequence of The World Is Not Enough. The Special Boat Service is based at RM Poole, home of the Navy's amphibious warfare section, off the B3068 at Hamworthy in the west of Poole. Tangerine Confectionery (former Parrs) made gums and jellies on the Redlands Trading Estate off the A3040 near Branksome railway station to the east. Aish Technologies makes console (display) systems for the Royal Navy off B3068 in Alderney.

Cobham plc, in Wimborne Minster towards Leigh, is a world-leader in air-to-air refuelling, developed by Alan Cobham at RAF Tarrant Rushton, and aircraft antennas. Durable UK (office products) is in Wimborne; Caterpillar's Wimborne Marine Power Centre make Perkins Sabre marine diesel generators on Ferndown Ind Est off the A31; to the south is the paint manufacturer Farrow & Ball in Hampreston and Stapehill, in Ferndown. Manitou UK, owner of the American Gehl Company and from Nanterre in France, is based at Verwood on the Ebblake Ind Est off the B3081 near the Hampshire boundary. Sigma-Aldrich UK (pharmaceuticals) are off the B3092 on Brickfield Business Park in Gillingham, next to the River Stour and railway. Cygnus Instruments, on the B3144 in Dorchester, is the leading manufacturer of ultrasonic thickness gauges, developing the technique in the early 1980s. Edwards Sports Products of Bridport, owned by Broxap of Staffordshire, make football goals for the Premier League, and tennis nets and posts for Wimbledon.[citation needed]

Gloucestershire

[edit]

In Cheltenham are Endsleigh Insurance in Shurdington, Kohler Mira Ltd (showers), Superdry (clothing), Collins Geo (maps), and Chelsea Building Society are on the A435 to the south-east. North of Cheltenham at Bishop's Cleeve, south of the village on the A435, is GE Aviation Systems UK on the large Cleeve Business Park; this which was the former 300-acre site of the Cheltenham Division of Smiths Industries that made flight control systems and flight deck displays; further up the A435 is a main site of Zurich Assurance UK. Weird Fish (clothing) is near Spirax-Sarco Engineering plc (pumps) off the A4019 in Kingsditch in Swindon Village, north of Cheltenham; on the other side of the A4019, Douglas Equipment, next to All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham, makes towing tractors for aircraft. Gulf Oil UK was headquartered on B4075 in Prestbury (near the racecourse) until 1997, when Shell UK bought its petrol stations; the former headquarters became a student hall of the University of Gloucestershire.

Computer security firm Symantec have a site in Gloucester, the base of Ecclesiastical Insurance. Dowty Rotol (who make propellers) and Bond Aviation Group (helicopter leasing) are next to Gloucestershire Airport at Staverton; Helimedia is the UK distributor of the L-3 Wescam, the Canadian thermal imaging system found with many UK police air support units and air ambulances. The Cheltenham & Gloucester bank was Barnwood (north Gloucester), next to Unilever's manufacturing site for Wall's ice cream at the A417/A38 roundabout next to the railway; on other side of the railway in Elmbridge is Lanes Health who make Olbas Oil and Kalms; to the south, EDF Energy (former British Energy) have their nuclear energy engineering centre with Horizon Nuclear Power. Between the former C&G and EDF at Barnwood, Barclays' data centre services all of its ATMs in the south of England.[citation needed]

Moog Controls UK, on the Ashchurch Ind Estate by Ashchurch for Tewkesbury near junction 9 (A46) of the M5, make servo valves for the aerospace industry (flight control systems or AFCS), in Northway; also on the estate is Steinhoff UK, who own Sleepmasters and Bensons for Beds. Floortex (floor coverings) is on Tewkesbury Business Park, west of the M5 south of Duraflex. Near the M5 Ashchurch Interchange off the A438, RR Donnelley GDS print Barclaycard statements. The Colt Car Company UK (who distribute Mitsubishi Motors) are in Cirencester, and Corin Group make artificial joints on the A429 near the Royal Agricultural University.

The Stroud & Swindon Building Society and Ecotricity are in Stroud near Stroud station. WSP Textiles (a former division of Milliken) on the A46 towards Rodborough in the south of Stroud make felt for billiard tables (Strachan cloth), and for tennis balls for three Grand Slam tournaments (Playne's tennis ball cloth). Dairy Crest makes Frijj milkshake at its large dairy at Severnside on the Stroudwater Business Park at Stonehouse next to the M5, within walking distance of Stonehouse station; nearby ReedHycalog (owned by National Oilwell Varco) make industrial drill bits off the A419 on the Oldends Ind Est, near ABB UK, who make flow meters; Delphi Diesel Systems UK, on the business park, make electronic unit injectors; Renishaw plc have large machining centre on north of the business park; SKF (Swedish) make ball bearings (Aeroengine & High Precision Bearings Division, for Rolls-Royce) to the south of the estate (former Ransome Hoffmann Pollard), then NSK until 2002); the company has another site at Clevedon in Somerset.

Beverage Brands is based at Hucclecote on the Gloucester Business Park off B4641 east of the M5 Brockworth Interchange, with Horizon Nuclear Power, and next to NHS Gloucestershire); in the same building is MessageLabs (Symantec), and a main office of Ageas UK (insurance). Further south in Brockworth is Direct Wines (Laithwaites); to the east is a G-TEKT (former Takao Europe) automotive metal pressings and sub-assemblies factory and a large Invista textiles factory (former ICI Fibres, then Dupont from 1992, which makes nylon fibres); the site is built on the former Gloster Aircraft factory, which closed around 1960. Renishaw plc is in Wotton-under-Edge, previously being in Nailsworth. Lister Petter, off the A4135 in Dursley, make diesel engine generator sets; Lister Shearing is the only British manufacturer of clipping and shearing (animals) equipment. The Fire Service College is in Moreton-in-Marsh near Moreton-in-Marsh station. Northcot Brick is at Blockley, in the north-east, next to the railway; Per Una is based near Draycott.

Mabey Group, off the A48 at Lydney make wind turbine towers; on the other side of the A48, Federal-Mogul have a foundry making camshafts. Suntory (Japanese) makes Lucozade (from 1957) and Ribena (from 1947) at the Royal Forest Factory off the B4228 in Coleford in the Forest of Dean; William Horlick, originator of another well-known former GSK product, was born in the Forest of Dean in 1846.

Somerset

[edit]

Screwfix is in Yeovil, and Clarks shoes with K-Swiss Europe are in Street, although most of its shoes are made in the Far East. Shepton Mallet is home of Blackthorn Cider and the Gaymer Cider Company. Dairy Crest packs Cathedral City cheese in Frome. The Glastonbury Festival at Pilton (nearer to Shepton Mallet than Glastonbury), off the A361, is the UK's biggest music festival.[148]

The Royal Marines have a large base for 40 Commando west of Taunton, with their training centre at Lympstone Commando in Devon, on the Avocet Line with its own station of Lympstone and the A376 and River Exe. Attentional in Taunton deliver audience figures for BARB. DS Smith's Wansbrough Paper Mill at Watchet on the coast is the UK's largest manufacturer of coreboard. Fletcher Boats make speedboats in Langport. TePe UK (Swedish) supply toothbrushes.

Thales Defence closed its radar site (former EMI Electronics) near Wookey Hole, in St Cuthbert Out. Thales Underwater Systems (former Plessey Marine) is at Abbas and Templecombe, Somerset, off the A357 towards Dorset in the Blackmore Vale, east of Yeovil. Commando Helicopter Force at Yeovilton operates Merlins and Wildcats (the upgraded version of the Lynx). Mulberry is based at Chilcompton on the B3139, north of Shepton Mallet, in the Mendips. Cox & Cox furnishings, is north of Frome in Berkley, Somerset off the A361. Fox Brothers make cloth in Wellington, and Relyon (part of Steinhoff International) make beds.

Italian defence contractor Leonardo makes helicopters at Yeovil, formerly the home of Westland Helicopters, building the AgustaWestland AW159 Wildcat. To the east of Yeovil, in Houndstone, Garador make garage doors (part of Hörmann Group of Amshausen, Europe's largest mechanical door manufacturer). Yeo Valley Organic is in Blagdon. Numatic International Limited makes vacuum cleaners in Chard, and Brecknell Willis, a railway engineering company on the A30, makes pantographs; ActionAid UK is in the Chard Business Centre, off the A358 in the north of Chard, near a centrifugal oil filter plant of Mann+Hummel. Dairy Crest made brandy butter south of the town in Tatworth and Forton, near the meeting point of Dorset, Somerset and Devon. Ministry of Cake, owned by Greencore since December 2007 on the A3065 in Staplegrove in the west of Taunton, is the leading provider of frozen desserts to the UK foodservice industry. The United Kingdom Hydrographic Office is in Taunton. Pilgrims Choice cheddar is made by Adams Foods (former North Downs Dairy) at Wincanton. Ariel Motor Company in Crewkerne, make the Ariel Atom.

Refresco Gerber in the north of Bridgwater, between the A38 and the River Parrett, make SunnyD, Libby's, Innocent Drinks, Del Monte, Just Juice and Ocean Spray.

Next to the Royal Portbury Dock, off junction 19 of the M5 on the A369 is Lafarge Plasterboard. Thatchers Cider is in Sandford, North Somerset on the A368, two miles east of the M5. Towards Bristol Airport, Claverham make actuation equipment for the aerospace sector in Yatton in North Somerset, off the A370, and is part of Hamilton Sundstrand, derived from the electrical systems part of Fairey Aviation.

Wessex Water, Future plc, Buro Happold and Rotork are in Bath. Cadbury used to make Curly Wurly, Double Decker and Crunchie at the Somerdale Factory, Keynsham until Kraft closed the plant in March 2011 and moved production to Skarbimierz, Opole Voivodeship in Poland.[149]

Wiltshire

[edit]

Nationwide Building Society,[150] Research Councils UK and five research councils, Intel Europe, and the British Computer Society[151] are in Swindon, as are the main offices of Historic England[152] and the National Trust,[153] both housed in the former Great Western Railway's Swindon Works. Allied Dunbar was headquartered in the centre of Swindon until 1998, when bought by Zurich Financial Services. In Stratton St Margaret, BMW press metal for the Mini[154] at the former Pressed Steel Company, there is a major Honda manufacturing plant (in South Marston) where the Jazz, Civic and CR-V are manufactured at Britain's second-largest car manufacturing plant;[155] nearby are Zimmer UK (medical devices) and Yuasa UK (automotive batteries).

The headquarters of WHSmith, with Smiths News, is near the School Library Association, west of the MINI works in Upper Stratton.[156] Valero Energy UK, who bought Texaco from Chevron in 2011, are in Eldene, in the former head office of St Ivel; Patheon UK (pharmaceuticals, on the former site of Roussel Uclaf) are on the B4006 in Covingham, north of Valero, in the east of Swindon. BG Automotive, on the Cheney Manor industrial estate, make gaskets on the B4006 in Rodbourne; Dynamatic UK are in a former Plessey factory. Burmah Oil was headquartered in the south of Swindon; Burmah bought Castrol in 1966 (owned by BP from 2000). Stanley Security (former Amano Blick) is on the Techno trading estate, north of the town centre.

Near the M4 Spittleborough Roundabout, close to Freshbrook, are Synergy Health and RWE npower; also on the Windmill Hill Business park are Arval (vehicle leasing and fuel cards), and Allstar (fuel card); also nearby are Cartus Europe, Catalent Pharma Solutions UK and MAN Truck & Bus UK (with Neoplan and ERF); further east is WRc (the former Water Research Centre). Nearby on Lydiard Fields in Lydiard Tregoze is Johnson Matthey Fuel Cells, which in 2002 was the world's first production site of membrane electrode assemblies, and next door is Neptune, who make furniture and kitchens; also BuildStore have their National Self Build & Renovation Centre. Sauer-Danfoss UK provide hydraulics off the A419 in Dorcan, and nearby is TE Connectivity UK (former Tyco Electronics and Raychem). The British & Foreign Bible Society is on the Delta Business Park in Westlea, near Intergraph UK (geospatial software, owned by Hexagon AB) on the other side of Westmead industrial estate, with Metric Group, the only UK manufacturer of parking meters. Triumph International UK is in Blunsdon St Andrew.