Leslie Feinberg

Leslie Feinberg | |

|---|---|

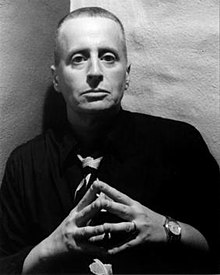

Feinberg taken by Ulrike Anhamm in 1997 | |

| Born | September 1, 1949 Kansas City, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | November 15, 2014 (aged 65) Syracuse, New York, U.S. |

| Occupation | Author, activist |

| Spouse | |

| Website | |

| transgenderwarrior | |

Leslie Feinberg (September 1, 1949 – November 15, 2014) was an American butch lesbian, transgender activist, communist,[1] and author.[2][3][4][5] Feinberg authored Stone Butch Blues in 1993.[6][7][8] Her[a] writing, notably Stone Butch Blues and her pioneering non-fiction book Transgender Warriors (1996), laid the groundwork for much of the terminology and awareness around gender studies and was instrumental in bringing these issues to a more mainstream audience.[3][4][9][10]

Early life

[edit]Feinberg was born in Kansas City, Missouri and raised in Buffalo, New York in a working-class, Jewish family. At fourteen years old, she began work at a display sign shop at a local department store. Feinberg eventually dropped out of Bennett High School, though she officially received a diploma. Feinberg began frequenting gay bars in Buffalo and primarily worked in low-wage and temporary jobs, including washing dishes, cleaning cargo ships, working as an ASL interpreter, inputting medical data, and working at a PVC pipe factory and a book bindery.[11][12]

Career

[edit]When Feinberg was in her twenties, she met members of the Workers World Party at a demonstration for the land rights and self-determination of Palestinians and joined the Buffalo branch of the party. After moving to New York City, Feinberg took part in anti-war, anti-racist, and pro-labor demonstrations on behalf of the party for many years, including the March Against Racism (Boston, 1974), a national tour about HIV/AIDS (1983–84), and a mobilization against KKK members (Atlanta, 1988).[11]

Feinberg began writing in the 1970s. As a member of the Workers World Party, she was the editor of the political prisoners page of the Workers World newspaper for fifteen years, and by 1995, she had become the managing editor.[11][13][14]

Feinberg's first novel, the 1993 Stone Butch Blues, won the Lambda Literary Award and the 1994 American Library Association Gay & Lesbian Book Award (now called the Stonewall Book Award).[15] While there are parallels to Feinberg's experiences as a working-class dyke, the work is not an autobiography.[6][7][8] Her second novel, Drag King Dreams, was released in 2006.[16]

Her nonfiction work included the books Transgender Liberation: A Movement Whose Time Has Come in 1992 and Transgender Warriors: Making History from Joan of Arc to Dennis Rodman in 1996. Also in 1996, Feinberg appeared in Rosa von Praunheim's documentary, Transexual Menace.[17] In 2009, she released Rainbow Solidarity in Defense of Cuba—a compilation of 25 journalistic articles.[18]

In Transgender Warriors, Feinberg defines "transgender" as a very broad umbrella, including all "people who cross the cultural boundaries of gender"[10]—including butch dykes, passing women (those who passed as men only in order to find work or survive during war), and drag queens.[9]

Feinberg's writings on LGBT history, "Lavender & Red", frequently appeared in the Workers World newspaper. Feinberg was awarded an honorary doctorate from Starr King School for the Ministry for transgender and social justice work.[19]

Feinberg was outspoken about her support for Palestinians. In a 2007 speech given to the first public conference of Aswat, an organization for LGBT Palestinian women, in Haifa in 2007, Feinberg said, "I am with Palestinian liberation with every breath in my body; every muscle and every sinew."[20] In a 2006[21] interview with Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore about Drag King Dreams, Feinberg said of her novel's Jewish characters, "for Heshie and Max, this question of the occupation of Palestine goes to the heart of what it means to live an authentic life in a period in which this really historical crime is taking place in their name."[22]

In June 2019 Feinberg was one of the inaugural fifty American "pioneers, trailblazers, and heroes" inducted on the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor within the Stonewall National Monument (SNM) in New York City's Stonewall Inn.[23][24] The SNM is the first U.S. national monument dedicated to LGBTQ rights and history,[25] and the wall's unveiling was timed to take place during the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots.[26]

Illness

[edit]In 2008, Feinberg was diagnosed with Lyme disease. She wrote that the infection first came about in the 1970s, when there was limited knowledge related to such diseases and that she felt hesitant to deal with medical professionals for many years due to her transgender identity. For this reason, she only received treatment later in life. In the 2000s, Feinberg created art and blogged about her illnesses with a focus on disability art and class consciousness.[11]

Personal life

[edit]Feinberg described herself as "an anti-racist white, working-class, secular Jewish, transgender, lesbian, female, revolutionary communist."[2][4][5]

According to Julie Enszer, a friend of Feinberg's, Feinberg sometimes "passed" as a man for safety reasons.[3]

Feinberg's spouse, Minnie Bruce Pratt, was a professor at Syracuse University in Syracuse, New York.[27][28] Feinberg and Pratt married in New York and Massachusetts in 2011.[29] In the mid and late 1990s they attended Camp Trans together.

Feinberg died on November 15, 2014, of complications due to multiple tick-borne infections, including "Lyme disease, babeisiosis, and protomyxzoa rheumatica", which she had suffered from since the 1970s.[2][30] Feinberg's last words were reported to be, "Hasten the revolution! Remember me as a revolutionary communist."[2]

Pronoun usage

[edit]Feinberg stated in a 2006 interview that her pronouns varied depending on context:

For me, pronouns are always placed within context. I am female-bodied, I am a butch lesbian, a transgender lesbian—referring to me as "she/her" is appropriate, particularly in a non-trans setting in which referring to me as "he" would appear to resolve the social contradiction between my birth sex and gender expression and render my transgender expression invisible. I like the gender neutral pronoun "ze/hir" because it makes it impossible to hold on to gender/sex/sexuality assumptions about a person you're about to meet or you've just met. And in an all trans setting, referring to me as "he/him" honors my gender expression in the same way that referring to my sister drag queens as "she/her" does.

Feinberg's widow wrote in her statement regarding Feinberg's death that Feinberg did not really care which pronouns a person used to address her: "She preferred to use the pronouns she/zie and her/hir for herself, but also said: 'I care which pronoun is used, but people have been respectful to me with the wrong pronoun and disrespectful with the right one. It matters whether someone is using the pronoun as a bigot, or if they are trying to demonstrate respect.'"[5]

Books

[edit]- Transgender Liberation: A Movement Whose Time Has Come. World View Forum, 1992. ISBN 0-89567-105-0.

- Stone Butch Blues. San Francisco: Firebrand Books, 1993. ISBN 1-55583-853-7.

- Transgender Warriors: Making History from Joan of Arc to Dennis Rodman. Boston: Beacon Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8070-7941-3.

- Trans Liberation: Beyond Pink or Blue. Beacon Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8070-7951-0

- Drag King Dreams. New York: Carroll & Graf, 2006. ISBN 0-7867-1763-7.

- Rainbow Solidarity in Defense of Cuba. New York: World View Forum, 2009. ISBN 0-89567-150-6.

See also

[edit]- Gender neutrality in languages with gendered third-person pronouns

- LGBT culture in New York City

- List of LGBT people from New York City

Notes

[edit]- ^ Feinberg used a variety of pronouns, however she favored she/her pronouns when writing for general audiences. As Wikipedia is written for a general audience, this article follows this guideline. For more information see § Pronoun usage.

References

[edit]- ^ Frey, Kate (January 9, 2015). "Leslie Feinberg: Transgender Warrior". Socialist Alternative. Archived from the original on April 10, 2019. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Transgender Pioneer and Stone Butch Blues Author Leslie Feinberg Has Died". Advocate. November 17, 2014. Archived from the original on May 7, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Weber, Bruce (November 25, 2014). "Leslie Feinberg, Writer and Transgender Activist, Dies at 65". New York Times. Archived from the original on March 28, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Author and transgender activist Leslie Feinberg is dead at 65". Los Angeles Times. November 18, 2014. Archived from the original on March 25, 2015. Retrieved February 17, 2015.

- ^ a b c Pratt, Minnie Bruce (November 18, 2014). "Leslie Feinberg – A communist who revolutionized transgender rights". Archived from the original on December 2, 2014. Retrieved February 17, 2015.

- ^ a b Violence and the body: race, gender, and the state Archived January 18, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Arturo J. Aldama; Indiana University Press, 2003; ISBN 978-0-253-34171-6.

- ^ a b Omnigender: A trans-religious approach Archived April 17, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Virginia R. Mollenkott, Pilgrim Press, 2001; ISBN 978-0-8298-1422-4.

- ^ a b Gay & lesbian literature, Volume 2 Archived January 18, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Sharon Malinowski, Tom Pendergast, Sara Pendergast; St. James Press, 1998; ISBN 978-1-55862-350-7.

- ^ a b Feinberg, Leslie (1997) Transgender Warriors: Making History from Joan of Arc to Dennis Rodman Boston: Beacon Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8070-7941-3

- ^ a b Feinberg, Leslie (2009) "Transgender Warriors Archived November 4, 2015, at the Wayback Machine" summary at Feinberg's Official Website Archived December 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Accessed October 19, 2015

- ^ a b c d "self". Leslie Feinberg. March 27, 2014. Archived from the original on May 14, 2019. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ "Leslie Feinberg". Syracuse.com. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ^ "Leslie Feinberg: New book, birthday celebrated" Archived January 11, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, LeiLani Dowell, September 9, 2009.

- ^ "Leftist transgender activist defies university censorship" Archived August 1, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Larry Hales, LeiLani Dowell; Ft. Collins, Colo.; April 27, 2005.

- ^ "Stonewall Book Awards List | Rainbow Roundtable". www.ala.org. Retrieved October 25, 2024.

- ^ Feinberg, Leslie (2006).Drag King Dreams. New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0-7867-1763-7.

- ^ "Transexual Menace". Mubi.com. Archived from the original on May 7, 2023. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ Feinberg, Leslie (2009). Rainbow Solidarity in Defense of Cuba (PDF) (1st ed.). New York, NY: World View Forum. ISBN 9780895671509. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 6, 2024. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "SKSM Honorary Degree Recipients". Starr King School for the Ministry. Archived from the original on June 25, 2018. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ "Leslie Feinberg to Aswat: 'I am at your side'". Workers World. April 12, 2007. Archived from the original on July 5, 2024. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "Finding Aid to the Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore Papers, 1990-2018". Online Archive of California. Archived from the original on June 21, 2024. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ Bernstein Sycamore, Mattilda (2006). "Interview with Leslie Feinberg. Originally published in the San Francisco Bay Guardian". Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore. Archived from the original on July 7, 2024. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ Glasses-Baker, Becca (June 27, 2019). "National LGBTQ Wall of Honor unveiled at Stonewall Inn". www.metro.us. Archived from the original on June 28, 2019. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^ Rawles, Timothy (June 19, 2019). "National LGBTQ Wall of Honor to be unveiled at historic Stonewall Inn". San Diego Gay and Lesbian News. Archived from the original on June 21, 2019. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- ^ Laird, Cynthia. "Groups seek names for Stonewall 50 honor wall". The Bay Area Reporter / B.A.R. Inc. Archived from the original on May 24, 2019. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ Sachet, Donna (April 3, 2019). "Stonewall 50". San Francisco Bay Times. Archived from the original on May 25, 2019. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ "Annual Philip J. Traci Memorial Reading Feb. 6". February 3, 2005. Archived from the original on September 29, 2011.

- ^ Winterton, Bradley (December 16, 2003). "A transgender warrior spreads the word to Taiwan". Taipei Times. Archived from the original on July 11, 2019. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- ^ Pengelly, Martin (November 17, 2014). "Leslie Feinberg, Stone Butch Blues author and transgender campaigner, dies at 65". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- ^ "Transgender Warrior". Leslie Feinberg Official Website. Archived from the original on May 17, 2011. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- ^ Tyroler, Jamie (July 28, 2006). "Transmissions – Interview with Leslie Feinberg". CampCK.com. Archived from the original on November 23, 2014. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

Further reading

[edit]- Lavender & Red, Feinberg's columns in Worker's World

- Partial Academic Bibliography by M.R. Cook Archived January 8, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- Partial curriculum vitae

External links

[edit]- 1949 births

- 2014 deaths

- 20th-century American novelists

- American political writers

- Jewish American novelists

- Jewish American activists

- Jewish socialists

- Lambda Literary Award winners

- Stonewall Book Award winners

- American lesbian writers

- Lesbian Jews

- American LGBTQ novelists

- LGBTQ people from Missouri

- American LGBTQ rights activists

- American secular Jews

- Jewish American anti-Zionists

- Transgender novelists

- Workers World Party politicians

- 20th-century American women writers

- American women novelists

- Writers from Kansas City, Missouri

- Writers from Buffalo, New York

- American communists

- Communist women writers

- Transgender Jews

- LGBTQ people from New York (state)

- Novelists from Missouri

- American women non-fiction writers

- Jewish American anti-racism activists

- American anti-racism activists

- Jewish women writers

- American transgender writers

- Transgender lesbians

- Jewish communists

- LGBTQ socialism