4179 Toutatis

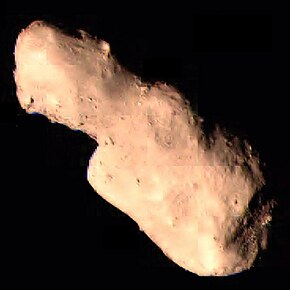

Toutatis imaged by Chang'e 2 during its flyby | |

| Discovery [1] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Christian Pollas |

| Discovery site | Caussols |

| Discovery date | 4 January 1989 |

| Designations | |

| (4179) Toutatis | |

| Pronunciation | /taʊˈteɪtɪs/ |

Named after | Toutatis (Celtic mythology)[2] |

| |

| Adjectives | Toutatian[4] |

| Orbital characteristics [3] | |

| Epoch 27 November 2008 (JD 2454797.5) | |

| Uncertainty parameter 0 | |

| Observation arc | 83.29 yr (30,422 days) |

| Earliest precovery date | 10 February 1934 |

| Aphelion | 4.1242 AU |

| Perihelion | 0.9399 AU |

| 2.5321 AU | |

| Eccentricity | 0.6288 |

| 4.03 yr (1,472 days) | |

| 5.1220° | |

| 0° 14m 40.56s / day | |

| Inclination | 0.4460° |

| 124.30° | |

| 278.75° | |

| Earth MOID | 0.0064 AU (2.5 LD) |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | |

| 2.45 km[6] | |

| Mass | 1.9×1013 kg[7] |

Mean density | 2.5 g/cm3[7] |

| 176 h (7.3 d)[8] | |

| 0.13[3] | |

| Sk (SMASSII)[3] | |

| 8.8–22.4[9][10] | |

| 15.30[3] | |

4179 Toutatis (provisional designation 1989 AC) is an elongated, stony asteroid and slow rotator,[11] classified as a near-Earth object and potentially hazardous asteroid of the Apollo asteroid group, approximately 2.5 kilometers in diameter. Discovered by French astronomer Christian Pollas at Caussols in 1989, the asteroid was named after Toutatis from Celtic mythology.[1][2]

Toutatis is also a Mars-crosser asteroid with a chaotic orbit produced by a 3:1 resonance with the planet Jupiter, a 1:4 resonance with the planet Earth, and frequent close approaches to the terrestrial planets, including Earth.[12] In December 2012, Toutatis passed within about 18 lunar distances of Earth. The Chinese lunar probe Chang'e 2 flew by the asteroid at a distance of 3.2 kilometers and a relative velocity of 10.73 km/s.[13] Toutatis approached Earth again in 2016, but will not make another notably close approach until 2069.[14]

Properties

[edit]Toutatis was first sighted on 10 February 1934, as object 1934 CT, but lost soon afterwards.[15] It remained a lost asteroid for several decades until it was rediscovered on 4 January 1989 by French astronomer Christian Pollas, and was named after the Celtic god of tribal protection Toutatis (Teutates). The name of this god is very familiar in France due to the catchphrase Par Toutatis! by the Gauls in the comics Asterix.[16]

The spectral properties suggest that this is an S-type, or stony asteroid, consisting primarily of silicates. It has a moderate Bond albedo of 0.13.[3] Radar imagery shows that Toutatis is a highly irregular body consisting of two distinct lobes, with maximum widths of about 4.6 km and 2.4 km, respectively. It is hypothesized that Toutatis formed from two originally separate bodies which coalesced at some point (a contact binary), with the resultant asteroid being compared to a rubble pile.

Its rotation combines two separate periodic motions into a non-periodic result; to someone on the surface of Toutatis, the Sun would seem to rise and set in apparently random locations and at random times at the asteroid's horizon. It has a rotation period around its long axis (Pψ) of 5.38 days. This long axis is precessing with a period (Pφ) of 7.38 days.[17] The asteroid may have lost most of its original angular momentum and entered into this tumbling motion as a result of the YORP effect.[18]

Orbit

[edit]

4179 Toutatis Sun · Earth · Jupiter

With a semimajor axis of 2.5294 AU, or roughly 2.5 times the distance between Earth and the Sun, Toutatis has a 3:1 orbital resonance with Jupiter and a near-1:4 resonance with Earth making it a member of the Alinda asteroid group.[12][19] It thus completes one orbit around the Sun for every 4.02 annual orbits of Earth. The gravitational perturbations caused by frequent close approaches to the terrestrial planets lead to chaotic behavior in the orbit of Toutatis,[20] making precise long-term predictions of its location progressively inaccurate over time.[20] Estimates in 1993 put the Lyapunov time horizon for predictability at around 50 years,[20] after which the uncertainty region becomes larger with each close approach to a planet. Without the perturbations from the terrestrial planets the Lyapunov time would be close to 10,000 years.[20] The initial observations that showed its chaotic behavior were made by Wiśniewski.[21]

The low inclination (0.47°) of the orbit allows frequent transits, where the inner planets Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars can appear to cross the Sun as seen from the perspective of Toutatis. Earth did this in January 2009, July 2012, July 2016 and 2020.[22]

Close approaches and collision risk

[edit]| Close approaches[14] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | AU | LD |

| 1985 | 0.28 | 109 |

| 1988 | 0.12 | 45 |

| 1992 | 0.02 | 9 |

| 1996 | 0.03 | 14 |

| 2000 | 0.07 | 29 |

| 2004 | 0.01 | 4 |

| 2008 | 0.05 | 20 |

| 2012 | 0.05 | 18 |

| 2016 | 0.25 | 98 |

| 2065 | 0.36 | 142 |

| 2069 | 0.02 | 8 |

Toutatis makes frequent close approaches to Earth, with a currently minimum possible distance (Earth MOID) of just 0.006 AU (2.3 times as far as the Moon).[3] The approach on 29 September 2004 was particularly close, at 0.0104 AU[23] (within 4 lunar distances) from Earth, presenting a good opportunity for observation, with Toutatis having an apparent magnitude of 8.8 at its brightest.[9] A close approach of 0.0502 AU (7,510,000 km; 4,670,000 mi) happened on 9 November 2008.[14][23] The most recent close approach was on 12 December 2012, at a distance of 0.046 AU (6,900,000 km; 4,300,000 mi),[14][23] with a magnitude of 10.7.[24] At magnitude 10.7, Toutatis was not visible to the naked eye, but just visible to experienced observers using high-end binoculars. During the 2012 encounter Toutatis was recovered on 21 May 2012, by the Siding Spring Survey at apparent magnitude 18.9.[25] A close approach will be 5 November 2069, at 0.01985 AU (2,970,000 km).[14]

Given that Toutatis makes many close approaches to Earth, such as in 1992, 1996, 2000, 2004, 2008, 2012, and 2016, it is listed as a potentially hazardous object.[14] With an uncertainty parameter of 0,[3] the orbit of Toutatis is very well determined for the next few hundred years.[14] The probability of the orbit intersecting Earth is essentially zero for at least the next six centuries.[26] The likelihood of collision in the distant future is considered to be very small.[27] As a planet-crossing asteroid, Toutatis is likely to be ejected from the inner Solar System within a few million years. In 2004 a chain e-mail falsely claimed that Toutatis had a 63% chance of impacting Earth then. In fact, Toutatis passed by at 1.5 million kilometres, or about four Earth–Moon distances, as predicted.[28]

In 2006 Toutatis came closer than 2 AU to Jupiter; its orbit lies inside of Jupiter's.[14] In the 2100s, it will approach Jupiter many times at a similar distance.[14]

| PHA | Date | Approach distance (lunar dist.) | Abs. mag (H) |

Diameter (C) (m) |

Ref (D) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nomi- nal(B) |

Mini- mum |

Maxi- mum | |||||

| (33342) 1998 WT24 | 1908-12-16 | 3.542 | 3.537 | 3.547 | 17.9 | 556–1795 | data |

| (458732) 2011 MD5 | 1918-09-17 | 0.911 | 0.909 | 0.913 | 17.9 | 556–1795 | data |

| (7482) 1994 PC1 | 1933-01-17 | 2.927 | 2.927 | 2.928 | 16.8 | 749–1357 | data |

| 69230 Hermes | 1937-10-30 | 1.926 | 1.926 | 1.927 | 17.5 | 668–2158 | data |

| 69230 Hermes | 1942-04-26 | 1.651 | 1.651 | 1.651 | 17.5 | 668–2158 | data |

| (137108) 1999 AN10 | 1946-08-07 | 2.432 | 2.429 | 2.435 | 17.9 | 556–1795 | data |

| (33342) 1998 WT24 | 1956-12-16 | 3.523 | 3.523 | 3.523 | 17.9 | 556–1795 | data |

| (163243) 2002 FB3 | 1961-04-12 | 4.903 | 4.900 | 4.906 | 16.4 | 1669–1695 | data |

| (192642) 1999 RD32 | 1969-08-27 | 3.627 | 3.625 | 3.630 | 16.3 | 1161–3750 | data |

| (143651) 2003 QO104 | 1981-05-18 | 2.761 | 2.760 | 2.761 | 16.0 | 1333–4306 | data |

| 2017 CH1 | 1992-06-05 | 4.691 | 3.391 | 6.037 | 17.9 | 556–1795 | data |

| (170086) 2002 XR14 | 1995-06-24 | 4.259 | 4.259 | 4.260 | 18.0 | 531–1714 | data |

| (33342) 1998 WT24 | 2001-12-16 | 4.859 | 4.859 | 4.859 | 17.9 | 556–1795 | data |

| 4179 Toutatis | 2004-09-29 | 4.031 | 4.031 | 4.031 | 15.3 | 2440–2450 | data |

| 2014 JO25 | 2017-04-19 | 4.573 | 4.573 | 4.573 | 17.8 | 582–1879 | data |

| (137108) 1999 AN10 | 2027-08-07 | 1.014 | 1.010 | 1.019 | 17.9 | 556–1795 | data |

| (35396) 1997 XF11 | 2028-10-26 | 2.417 | 2.417 | 2.418 | 16.9 | 881–2845 | data |

| (154276) 2002 SY50 | 2071-10-30 | 3.415 | 3.412 | 3.418 | 17.6 | 714–1406 | data |

| (164121) 2003 YT1 | 2073-04-29 | 4.409 | 4.409 | 4.409 | 16.2 | 1167–2267 | data |

| (385343) 2002 LV | 2076-08-04 | 4.184 | 4.183 | 4.185 | 16.6 | 1011–3266 | data |

| (52768) 1998 OR2 | 2079-04-16 | 4.611 | 4.611 | 4.612 | 15.8 | 1462–4721 | data |

| (33342) 1998 WT24 | 2099-12-18 | 4.919 | 4.919 | 4.919 | 17.9 | 556–1795 | data |

| (85182) 1991 AQ | 2130-01-27 | 4.140 | 4.139 | 4.141 | 17.1 | 1100 | data |

| 314082 Dryope | 2186-07-16 | 3.709 | 2.996 | 4.786 | 17.5 | 668–2158 | data |

| (137126) 1999 CF9 | 2192-08-21 | 4.970 | 4.967 | 4.973 | 18.0 | 531–1714 | data |

| (290772) 2005 VC | 2198-05-05 | 1.951 | 1.791 | 2.134 | 17.6 | 638–2061 | data |

| (A) List includes near-Earth approaches of less than 5 lunar distances (LD) of objects with H brighter than 18. (B) Nominal geocentric distance from the Earth's center to the object's center (Earth radius≈0.017 LD). (C) Diameter: estimated, theoretical mean-diameter based on H and albedo range between X and Y. (D) Reference: data source from the JPL SBDB, with AU converted into LD (1 AU≈390 LD) (E) Color codes: unobserved at close approach observed during close approach upcoming approaches | |||||||

Physical characteristics

[edit]Large amounts of data of Toutatis were obtained during Chang'e 2's flyby. Toutatis is not a monolith, but most likely a coalescence of shattered fragments. This bifurcated asteroid is shown to be mainly consisting of a head (small lobe) and a body (large lobe). The two major parts are not round in shape, and their surfaces have a number of large facets. In comparison with radar models, the proximate observations from Chang'e 2's flyby have revealed several remarkable discoveries concerning Toutatis, among which the presence of the giant basin at the big end appears to be one of the most compelling geological features, and the sharply perpendicular silhouette in the neck region that connects the head and body is also quite novel. A large number of boulders and several short linear structures are also apparent on the surface.[5]

Giant basin

[edit]The giant basin at the big end of Toutatis has a diameter of ~805 m, suggesting that one or more impactors may have collided with it there. The most significant feature is the ridge around the largest basin. The wall of this basin has a relatively high density of lineaments, some of which seem to be concentric to the basin. These ridges are indicative of an internal structure of small bodies and most of the ridges near the largest basin at the big end are most likely related to the huge stress energy during impact.[5]

Observation

[edit]Toutatis has been observed with radar imaging from the Arecibo Observatory and the Goldstone Solar System Radar during the asteroid's prior Earth flybys in 1992, 1996, 2000, 2004, and 2008. It was also observed with radar during the December 2012 flyby and observed more distant flyby with radar in December 2016.[29] After 2016, Toutatis will not pass close to Earth again until 2069.

Resolution of the radar images is as fine as 3.75 m per pixel,[30] providing data to model Toutatis's shape and spin state.

Exploration

[edit]

The Chinese lunar probe Chang'e 2 departed from the Sun–Earth L2 point in April 2012[31] and made a flyby of Toutatis on 13 December 2012, with closest approach being 3.2 kilometers and a relative velocity of 10.73 km/s, when Toutatis was near its closest approach to Earth.[13][32][33] It took several pictures of the asteroid, revealing it to be a dusty red/orange color.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "4179 Toutatis (1989 AC)". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ^ a b Schmadel, Lutz D. (2007). "(4179) Toutatis". Dictionary of Minor Planet Names – (4179) Toutatis. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 357–358. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-29925-7_4150. ISBN 978-3-540-00238-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 4179 Toutatis (1989 AC)" (2017-05-27 last obs.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ^ Hudson, "Gravitational Isopotentials on Toutatis"

- ^ a b c Huang, Jiangchuan; Ji, Jianghui; Ye, Peijian; Wang, Xiaolei; Yan, Jun; Meng, Linzhi; Wang, Su; Li, Chunlai; Li, Yuan; Qiao, Dong; Zhao, Wei; Zhao, Yuhui; Zhang, Tingxin; Liu, Peng; Jiang, Yun; Rao, Wei; Li, Sheng; Huang, Changning; Ip, Wing-Huen; Hu, Shoucun; Zhu, Menghua; Yu, Liangliang; Zou, Yongliao; Tang, Xianglong; Li, Jianyang; Zhao, Haibin; Huang, Hao; Jiang, Xiaojun; Bai, Jinming (2013). "The Ginger-shaped Asteroid 4179 Toutatis: New Observations from a Successful Flyby of Chang'e-2 : Scientific Reports : Nature Publishing Group". Scientific Reports. 3: 3411. arXiv:1312.4329. Bibcode:2013NatSR...3E3411H. doi:10.1038/srep03411. PMC 3860288. PMID 24336501.

- ^ a b Hudson, R. S.; Ostro, S. J.; Scheeres, D. J. (February 2003). "High-resolution model of Asteroid 4179 Toutatis". Icarus. 161 (2): 346–355. Bibcode:2003Icar..161..346H. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.494.7779. doi:10.1016/S0019-1035(02)00042-8.

- ^ a b Scheeres, D. J.; Ostro, S. J.; Hudson, R. S. (March 1998). "Dynamics of Orbits Close to Asteroid 4179 Toutatis". Icarus. 132 (1): 53–79. Bibcode:1998Icar..132...53S. doi:10.1006/icar.1997.5870.

- ^ "LCDB Data for (4179) Toutatis". Asteroid Lightcurve Database (LCDB). Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ^ a b "AstDys (4179) Toutatis Ephemerides for 2004". Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ "AstDys (4179) Toutatis Ephemerides 2059". Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ "Asteroid 4179 Toutasis". NASA. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Trick or Treat: It's Toutatis!". Science@Nasa. 31 October 2000. Archived from the original on 29 January 2009. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- ^ a b Lakdawalla, Emily (14 December 2012). "Chang'E 2 imaging of Toutatis succeeded beyond my expectations!". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "JPL Close-Approach Data: 4179 Toutatis (1989 AC)" (2011-05-22 last obs (arc=77.28 years)). Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "(4179) Toutatis = 1934 CT = 1989 AC". IAU Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ "By Toutatis! France unveils statue to Asterix creator". France 24. 23 January 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ Mueller, Béatrice E. A.; Samarasinha, Nalin H.; Belton, Michael J. S. (August 2002). "The Diagnosis of Complex Rotation in the Lightcurve of 4179 Toutatis and Potential Applications to Other Asteroids and Bare Cometary Nuclei". Icarus. 158 (2): 305–311. Bibcode:2002Icar..158..305M. doi:10.1006/icar.2002.6892.

- ^ Bottke, William Jr. (October 2007). "Implications of the YORP Effect for Our Understanding of Asteroid Evolution". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 39: 416. Bibcode:2007DPS....39.0507B.

- ^ "Toutatis is in a 3:1 mean-motion resonance with Jupiter (rotating frame)". Gravity Simulator. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d Whipple, L.; Shelus, Peter J. (1993). "Long-Term Dynamical Evolution of the Minor Planet (4179) Toutatis". Icarus. 105 (2): 408–419. Bibcode:1993Icar..105..408W. doi:10.1006/icar.1993.1137.

- ^ "The Minor Planet Bulletin" (PDF). Association of Lunar and Planetary Onservers. 1994. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- ^ "Solex by Aldo Vitagliano". Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 3 March 2009.

- ^ a b c "NEODys (4179) Toutatis Close Approaches". Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- ^ "NEODys (4179) Toutatis Ephemerides for December 2012". Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ "(4179) Toutatis = 1934 CT = 1989 AC". IAU Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ^ Ostro, S. J.; Hudson, R. S.; Rosema, K. D.; Giorgini, J. D.; et al. (1998). "Asteroid 4179 Toutatis: 1996 Radar Observations" (PDF). Icarus. 137 (1): 122–139. Bibcode:1999Icar..137..122O. doi:10.1006/icar.1998.6031. hdl:2014/19433. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2017.

- ^ "Close call for earth ahead? – possible collision with asteroid Toutatis". USA Today (Society for the Advancement of Education). 1993. Archived from the original on 28 June 2012.

- ^ David Morrison (27 September 2004). "Close Flyby This Week from Asteroid Toutatis". Asteroid and Comet Impact Hazards (NASA). Archived from the original on 14 February 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ "2012 Goldstone Radar Observations of (4179) Toutatis". Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ "Big Asteroid Tumbles Harmlessly Past Earth". NASA. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ^ Lakdawalla, Emily (14 June 2012). "Chang'E 2 has departed Earth's neighborhood for.....asteroid Toutatis!?". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ ""Pseudo-MPEC" for 2010-050A = SM999CF = Chang'e 2 probe". Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ "[视频]"嫦娥二号"飞越探测小行星_新闻台_中国网络电视台". News.cntv.cn. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

External links

[edit]- More Chang'E 2 Toutatis flyby images (Emily Lakdawalla : 2013/01/20)

- Chang'E 2 images of Toutatis - 13 December 2012 Archived 29 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine (Planetary Society)

- CCTV13 Special (all in Mandarin)

- China joined the interplanetary club by successfully imaging the asteroid Toutatis (Franck Marchis, 14 December 2012)

- Chinese space probe flies by asteroid Toutatis (Xinhua 2012-12-15)

- Surface Features of Asteroid Toutatis Revealed by Radar (YouTube: JPLnews)

- Goldstone radar images from the 2012 flyby

- Toutatis radar information

- Space.com: Video of Toutatis's close approach to Earth, 29 Sept, 2004

- Interesting views of asteroid

- Astrobiology Magazine article (09/27/04)

- Simulating the orbit of Toutatis exposes its resonance with Jupiter (Gravity Simulator)

- Asteroid 4179 Toutatis' upcoming encounters with Earth and Chang'E 2 (Emily Lakdawalla 2012-12-06)

- Six-Centimeter Radar Observations of 4179 Toutatis

- Size comparison (Source)

- Chang'e 2 fly-by of Toutatis Presentation from Small Bodies Assessment Group (SBAG) 8 meeting

- Boulders on asteroid Toutatis as observed by Chang'e-2 (arXiv:1511.00766 : 3 Nov 2015)

- 4179 Toutatis at AstDyS-2, Asteroids—Dynamic Site

- 4179 Toutatis at ESA–space situational awareness

- 4179 Toutatis at the JPL Small-Body Database

- Minor planet object articles (numbered)

- Apollo asteroids

- Alinda asteroids

- Discoveries by Christian Pollas

- Named minor planets

- Potentially hazardous asteroids

- Radar-imaged asteroids

- Minor planets visited by spacecraft

- Slow rotating minor planets

- Sk-type asteroids (SMASS)

- Near-Earth objects in 2012

- Astronomical objects discovered in 1989