Marwan I

| Marwan I مروان | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Drachma of Marwan I | |||||

| 4th Caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate | |||||

| Reign | June 684 – April/May 685 | ||||

| Predecessor | Mu'awiya II | ||||

| Successor | Abd al-Malik | ||||

| Born | 623 or 626 Mecca, Hejaz, Arabia | ||||

| Died | April/May 685 (aged 59–63) Damascus or al-Sinnabra, Umayyad Caliphate | ||||

| Spouse |

| ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Marwanid | ||||

| Dynasty | Umayyad | ||||

| Father | Al-Ḥakam ibn Abī al-ʿAs | ||||

| Mother | Āmina bint ʿAlqama al-Kinānīyya | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

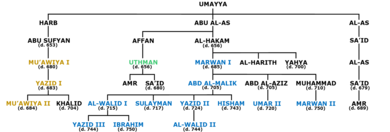

Marwan ibn al-Hakam ibn Abi al-As ibn Umayya (Arabic: مروان بن الحكم بن أبي العاص بن أمية, romanized: Marwān ibn al-Ḥakam ibn Abī al-ʿĀṣ ibn Umayya; 623 or 626 – April/May 685), commonly known as Marwan I, was the fourth Umayyad caliph, ruling for less than a year in 684–685. He founded the Marwanid ruling house of the Umayyad dynasty, which replaced the Sufyanid house after its collapse in the Second Fitna and remained in power until 750.

During the reign of his cousin Uthman (r. 644–656), Marwan took part in a military campaign against the Byzantines of the Exarchate of Africa (in central North Africa), where he acquired significant war spoils. He also served as Uthman's governor in Fars (southwestern Iran) before becoming the caliph's katib (secretary or scribe). He was wounded fighting the rebel siege of Uthman's house, in which the caliph was slain. In the ensuing civil war between Ali (r. 656–661) and the largely Qurayshite partisans of A'isha, Marwan sided with the latter at the Battle of the Camel. Marwan later served as governor of Medina under his distant kinsman Caliph Mu'awiya I (r. 661–680), founder of the Umayyad Caliphate. During the reign of Mu'awiya's son and successor Yazid I (r. 680–683), Marwan organized the defense of the Umayyad realm in the Hejaz (western Arabia) against the local opposition which included prominent companions as well as Muhammad’s own clan, the Bani Hashim, who revolted under the banner of Muhammad’s grandson, Husayn ibn Ali. After Yazid died in November 683, the Mecca-based rebel Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr declared himself caliph and expelled Marwan, who took refuge in Syria, the center of Umayyad rule. With the death of the last Sufyanid caliph Mu'awiya II in 684, Marwan, encouraged by the ex-governor of Iraq Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad, volunteered his candidacy for the caliphate during a summit of pro-Umayyad tribes in Jabiya. The tribal nobility, led by Ibn Bahdal of the Banu Kalb, elected Marwan and together they defeated the pro-Zubayrid Qays tribes at the Battle of Marj Rahit in August of that year.

In the months that followed, Marwan reasserted Umayyad rule over Egypt, Palestine, and northern Syria, whose governors had defected to Ibn al-Zubayr's cause, while keeping the Qays in check in the Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia). He dispatched an expedition led by Ibn Ziyad to reconquer Zubayrid Iraq, but died while it was underway in the spring of 685. Before his death, Marwan firmly established his sons in positions of power: Abd al-Malik was designated his successor, Abd al-Aziz was made governor of Egypt, and Muhammad oversaw military command in Upper Mesopotamia. Although Marwan was stigmatized as an outlaw and a father of tyrants in later anti-Umayyad tradition, the historian Clifford E. Bosworth asserts that the caliph was a shrewd, capable, and decisive military leader and statesman who laid the foundations of continued Umayyad rule for a further sixty-five years.

Early life and family

[edit]

Marwan was born in 2 or 4 AH (623 or 626 CE).[2] His father was al-Hakam ibn Abi al-As of the Banu Umayya (Umayyads), the strongest clan of the Quraysh, a polytheistic tribe which dominated the town of Mecca in the Hejaz.[2][3] The Quraysh converted to Islam en masse in c. 630 following the conquest of Mecca by the Islamic prophet Muhammad, himself a member of the Quraysh.[4] Marwan knew Muhammad and is thus counted among the latter's sahaba (companions).[2] Marwan's mother was Amina bint Alqama of the Kinana,[2] the ancestral tribe of the Quraysh which dominated the area stretching southwest from Mecca to the Tihama coastline.[5]

Marwan had at least sixteen children, among them at least twelve sons from five wives and an umm walad (concubine).[6] From his wife A'isha, a daughter of his paternal first cousin Mu'awiya ibn al-Mughira, he had his eldest son Abd al-Malik, Mu'awiya and daughter Umm Amr.[6][7] Umm Amr later married Sa'id ibn Khalid ibn Amr, a great-grandson of Marwan's paternal first cousin Uthman ibn Affan, who became caliph (leader of the Muslim community) in 644.[8] Marwan's wife Layla bint Zabban ibn al-Asbagh of the Banu Kalb tribe bore him Abd al-Aziz and daughter Umm Uthman,[6] who was married to Caliph Uthman's son al-Walid; al-Walid was also married at one point to Marwan's daughter Umm Amr.[7] Another of Marwan's wives, Qutayya bint Bishr of the Banu Kilab, bore him Bishr and Abd al-Rahman, the latter of whom died young.[6][7] One of Marwan's wives, Umm Aban al-Kubra, was a daughter of Caliph Uthman.[6] She was mother to six of his sons, Aban, Uthman, Ubayd Allah, Ayyub, Dawud and Abd Allah, though the last of them died a child.[6][9] Marwan was married to Zaynab bint Umar, a granddaughter of Abu Salama from the Banu Makhzum, who mothered his son Umar.[6][10] Marwan's umm walad was also named Zaynab and gave birth to his son Muhammad.[6] Marwan had ten brothers and was the paternal uncle of ten nephews.[11]

Secretary of Uthman

[edit]During the reign of Caliph Uthman (r. 644–656), Marwan took part in a military campaign against the Byzantines of the Exarchate of Carthage (in central North Africa), where he acquired significant war spoils.[2][12] These likely formed the basis of Marwan's substantial wealth, part of which he invested in properties in Medina,[2] the capital of the Caliphate. At an undetermined point, he served as Uthman's governor in Fars (southwestern Iran) before becoming the caliph's katib (secretary or scribe) and possibly the overseer of Medina's treasury.[2][13] According to the historian Clifford E. Bosworth, in this capacity Marwan "doubtless helped" in the revision "of what became the canonical text of the Qur'an" in Uthman's reign.[2]

The historian Hugh Kennedy asserts that Marwan was the caliph's "right-hand man".[14] According to the traditional Muslim reports, many of Uthman's erstwhile backers among the Quraysh gradually withdrew their support as a result of Marwan's pervasive influence, which they blamed for the caliph's controversial decisions.[13][15][16] The historian Fred Donner questions the veracity of these reports, citing the unlikelihood that Uthman would be highly influenced by a younger relative such as Marwan and the rarity of specific charges against the latter, and describes them as a possible "attempt by later Islamic tradition to salvage Uthman's reputation as one of the so-called 'rightly-guided' (rāshidūn) caliphs by making Marwan ... the fall guy for the unhappy events at the end of Uthman's twelve-year reign."[13]

Discontent over Uthman's nepotistic policies and confiscation of the former Sasanian crown lands in Iraq[a] drove the Quraysh and the dispossessed elites of Kufa and Egypt to oppose the caliph.[18] In early 656, rebels from Egypt and Kufa entered Medina to press Uthman to reverse his policies.[19] Marwan recommended a violent response against them.[20] Instead, Uthman entered into a settlement with the Egyptians, the largest and most outspoken group among the mutineers.[21] On their return to Egypt, the rebels intercepted a letter in Uthman's name to Egypt's governor, Ibn Abi Sarh, instructing him to take action against the rebels.[21] In reaction, the Egyptians marched back to Medina and besieged Uthman in his home in June 656.[21] Uthman claimed to have been unaware of the letter, and it may have been authored by Marwan without Uthman's knowledge.[21] Despite orders to the contrary,[22] Marwan actively defended Uthman's house and was badly wounded in the neck when he challenged the rebels assembled at its entrance.[2][13][23] According to tradition, he was saved by the intervention of his wet nurse, Fatima bint Aws, and was transported to the safety of her home by his mawla (freedman or client), Abu Hafs al-Yamani.[23] Shortly after, Uthman was assassinated by the rebels,[21] which became one of the major contributing factors to the First Fitna.[24] After the assassination, Marwan and other Umayyads fled to Mecca.[25] Calls for avenging Uthman's death were led by the Umayyads, one of Muhammad's wives, A'isha, and two of his prominent companions, al-Zubayr ibn al-Awwam and Talha ibn Ubayd Allah. Punishing Uthman's murderers became a rallying cry of the opposition to his successor, Ali ibn Abi Talib, a cousin and son-in-law of Muhammad.[26]

Role in the First Fitna

[edit]In the ensuing hostilities between Ali and the largely Qurayshite partisans of A'isha, Marwan sided with the latter.[2] He fought alongside A'isha's forces at the Battle of the Camel near Basra in December 656.[2] The historian Leone Caetani presumed that Marwan was the organizer of A'isha's strategy there.[27] The modern historian Laura Veccia Vaglieri notes that while Caetani's "theory is attractive", there is no information in the traditional sources to confirm it and should Marwan have been A'isha's war adviser "he operated so discreetly that the sources hardly speak of his actions."[27]

According to one version in the Islamic tradition, Marwan used the occasion of the battle to kill a partisan of A'isha, Talha, whom he held especially responsible for instigating Uthman's death.[2] Marwan had fired an arrow at Talha, which struck the sciatic vein below his knee, as their troops fell back in a hand-to-hand fight with Ali's soldiers.[28] The historian Wilferd Madelung notes that Marwan "evidently" waited to kill Talha when A'isha appeared close to defeat and thus in a weak position to call Marwan to account for his action.[28] Another version in the tradition attributes Talha's death to Ali's supporters during Talha's retreat from the field,[29] and Caetani dismisses Marwan's culpability as a fabrication by the generally anti-Umayyad sources.[30] Madelung holds that Marwan's slaying of Talha is corroborated by Umayyad propaganda in the 680s heralding him as the first person to take revenge for Uthman's death by killing Talha.[30]

After the battle ended with Ali's victory, Marwan pledged his allegiance to him.[2] Ali pardoned him and Marwan left for Syria, where his distant cousin Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan, who refused allegiance to Ali, was governor.[31] Marwan was present alongside Mu'awiya at the Battle of Siffin near Raqqa in 657,[32] which ended in a stalemate with Ali's army and abortive arbitration talks to settle the civil war.[33]

Governor of Medina

[edit]

Ali was assassinated by a member of the Kharijites, a sect opposed to both Ali and Mu'awiya, in January 661.[34] His son and successor Hasan ibn Ali abdicated in a peace treaty with Mu'awiya, who entered Hasan's and formerly Ali's capital at Kufa and gained recognition as caliph there in July or September, marking the establishment of the Umayyad Caliphate.[34][35] Marwan served as Mu'awiya's governor in Bahrayn (eastern Arabia) before serving two stints as governor of Medina in 661–668 and 674–677.[2] In between those two terms, Marwan's Umayyad kinsmen Sa'id ibn al-As and al-Walid ibn Utba ibn Abi Sufyan held the post.[2] Medina had lost its status as the political center of the Caliphate in the aftermath of Uthman's assassination. Under Mu'awiya the capital shifted to Damascus.[36] Although it was reduced to a provincial governorship, Medina remained a hub of Arab culture and Islamic scholarship and home of the traditional Islamic aristocracy.[37] The old elites in Medina, including most of the Umayyad family, resented their loss of power to Mu'awiya; in the summation of the historian Julius Wellhausen, "of what consequence was Marwan, formerly the all-powerful imperial chancellor of Uthman, now as Emir of Medina! No wonder he cast envious looks at his cousin of Damascus who had so far outstripped him."[38]

During his first term, Marwan acquired from Mu'awiya a large estate in the Fadak oasis in northwestern Arabia, which he then bestowed on his sons Abd al-Malik and Abd al-Aziz.[2] Marwan's first dismissal from the governorship caused him to travel to Mu'awiya's court for an explanation from the caliph, who listed three reasons: Marwan's refusal to confiscate for Mu'awiya the properties of their relative Abd Allah ibn Amir after the latter's dismissal from the governorship of Basra; Marwan's criticism of the caliph's adoption of the fatherless Ziyad ibn Abihi, Ibn Amir's successor in Basra, as the son of his father Abu Sufyan, which the Umayyad family disputed; and Marwan's refusal to assist the caliph's daughter Ramla in a domestic dispute with her husband, Amr ibn Uthman ibn Affan.[39] In 670, Marwan led Umayyad opposition to the attempted burial of Hasan ibn Ali beside the grave of Muhammad, compelling Hasan's brother, Husayn, and his clan, the Banu Hashim, to abandon their original funeral arrangement and bury Hasan in the al-Baqi cemetery instead.[40] Afterward, Marwan participated in the funeral and eulogized Hasan as one "whose forbearance weighed mountains".[41]

According to Bosworth, Mu'awiya may have been suspicious of the ambitions of Marwan and the Abu al-As line of the Banu Umayya in general, which was significantly more numerous than the Abu Sufyan (Sufyanid) line to which Mu'awiya belonged.[11] Marwan was among the eldest and most prestigious Umayyads at a time when there were few experienced Sufyanids of mature age.[11] Bosworth speculates that it "may have been fears of the family of Abu'l-ʿĀs that impelled Muʿāwiya to his adoption of his putative half-brother Ziyād b. Sumayya [Ziyad ibn Abihi] and to the unusual step of naming his own son Yazīd as heir to the caliphate during his own lifetime".[11][b] Marwan had earlier pressed Uthman's son Amr to claim the caliphate based on the legitimacy of his father, a member of the Abu al-As branch, but Amr was uninterested.[44] Marwan reluctantly accepted Mu'awiya's nomination of Yazid in 676, but quietly encouraged another son of Uthman, Sa'id, to contest the succession.[45] Sa'id's ambitions were neutralized when the caliph gave him military command in Khurasan, the easternmost region of the Caliphate.[46]

Leader of the Umayyads in Medina

[edit]After Mu'awiya died in 680, the grandson of Muhammad, Husayn ibn Ali, as well as Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr and Abd Allah ibn Umar, both sons of prominent Qurayshite companions of Muhammad with their own claims to the caliphate,[47] continued to refuse allegiance to Mu'awiya's chosen successor Yazid.[48] Marwan, the leader of the Umayyad clan in the Hejaz,[49] advised al-Walid ibn Utba, then governor of Medina, to coerce Husayn and Ibn al-Zubayr, both of whom he considered especially dangerous to Umayyad rule, to accept the caliph's sovereignty.[50] Husayn answered al-Walid's summons, but refused to pledge allegiance to Yazid because he considered him to be a transgressor against the Quran and the Prophet’s teachings. Husayn left Madina and was called to the city of Kufa. He sent his cousin, Muslim ibn Aqil, as an emissary to the city. Muslim wrote a letter to Husayn that stated that the people welcomed him. The people of Kufa shortly betrayed Muslim after the letter was sent to Husayn. Ibn Ziyad, the governor of Kufa, had Muslim executed.

Husayn learnt that Muslim was killed. He changed his course towards the east and intended to leave peacefully to avoid conflict. He was stopped by Yazid’s forces and was brutally killed at the Battle of Karbala.

Meanwhile, Ibn al-Zubayr avoided al-Walid's summons and escaped to Mecca, where he rallied opposition to Yazid from his headquarters in the Ka'aba, Islam's holiest sanctuary where violence was traditionally banned.[51] In the Islamic traditional anecdotes relating Yazid's response, Marwan warns Ibn al-Zubayr not to submit to the caliph;[52] Wellhausen considers these variable traditions to be unreliable.[53] In 683, the people of Medina rebelled against the caliph and assaulted the local Umayyads and their supporters, prompting them to take refuge in Marwan's houses in the city's suburbs where they were besieged.[54][55] In response to Marwan's plea for assistance,[54] Yazid dispatched an expeditionary force of Syrian tribesmen led by Muslim ibn Uqba to assert Umayyad authority over the region.[11] The Umayyads of Medina were afterward expelled and many, including Marwan and the Abu al-As family, joined Ibn Uqba's expedition.[11] In the ensuing Battle of al-Harra in August 683, Marwan led his horsemen through Medina and launched a rear assault against the Medinese defenders fighting Ibn Uqba in the city's eastern outskirts.[56] Despite its victory over the Medinese, Yazid's army retreated to Syria in the wake of the caliph's death in November.[49] On the Syrians' departure, Ibn al-Zubayr declared himself caliph and soon gained recognition in most of the Caliphate's provinces, including Egypt, Iraq and Yemen.[57] Marwan and the Umayyads of the Hejaz were expelled for a second time by Ibn al-Zubayr's partisans and their properties were confiscated.[11]

Caliphate

[edit]Accession

[edit]

By early 684, Marwan was in Syria, either at Palmyra or in the court of Yazid's young son and successor, Mu'awiya II, in Damascus.[11] The latter died several weeks into his reign without designating a successor.[58] The governors of the Syrian junds (military districts) of Palestine, Homs and Qinnasrin subsequently gave their allegiance to Ibn al-Zubayr.[11] As a result, Marwan "despaired over any future for the Umayyads as rulers", according to Bosworth, and was prepared to recognize Ibn al-Zubayr's legitimacy.[11] However, he was encouraged by the expelled governor of Iraq, Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad, to volunteer himself as Mu'awiya II's successor during a summit of loyalist Syrian Arab tribes being held in Jabiya.[11] The bids for leadership of the Muslim community exposed the conflict between three developing principles of succession.[59] The general recognition of Ibn al-Zubayr adhered to the Islamic principle of passing leadership to the most righteous and eminent Muslim,[59] while the Umayyad loyalists at the Jabiya summit debated the two other principles: direct hereditary succession as introduced by Mu'awiya I and represented by the nomination of his adolescent grandson Khalid ibn Yazid; and the Arab tribal norm of selecting the wisest and most capable member of a tribe's leading clan, epitomized in this case by Marwan.[60]

The organizer of the Jabiya summit, Ibn Bahdal, the chieftain of the powerful Banu Kalb tribe and maternal cousin of Yazid,[49] supported Khalid's nomination.[11][14] Most of the other chieftains, led by Rawh ibn Zinba of the Judham and Husayn ibn Numayr of the Kinda,[11] opted for Marwan, citing his mature age, political acumen and military experience, over Khalid's youth and inexperience.[61] The 9th-century historian al-Ya'qubi quotes Rawh heralding Marwan: "People of Syria! This is Marwān b. al-Ḥakam, the chief of Quraysh, who avenged the blood of ʿUthmān and fought ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib at the Battle of the Camel and Ṣiffīn."[62] A consensus was ultimately reached on 22 June 684 (29 Shawwal 64 AH), whereby Marwan would accede to the caliphate,[63] followed by Khalid and then Amr ibn Sa'id ibn al-As, another prominent young Umayyad.[11] In exchange for backing Marwan, the loyalist Syrian tribes, who shortly thereafter became known as the "Yaman" faction (see below), were promised financial compensation.[14] The Yamani ashraf (tribal nobility) demanded from Marwan the same courtly and military privileges they held under the previous Umayyad caliphs.[64] Husayn ibn Numayr had attempted to reach a similar arrangement with Ibn al-Zubayr, who publicly rejected the terms.[65] In contrast, Marwan "realized the importance of the Syrian troops and adhered wholeheartedly to their demands", according to the historian Mohammad Rihan.[66] In the summation of Kennedy, "Marwān had no experience or contacts in Syria; he would be entirely dependent on the ashrāf from the Yamanī tribes who had elected him."[14]

Campaigns to reassert Umayyad rule

[edit]

In opposition to the Kalb, the pro-Zubayrid Qaysi tribes objected to Marwan's accession and beckoned al-Dahhak ibn Qays al-Fihri, the governor of Damascus, to mobilize for war; accordingly, al-Dahhak and the Qays set up camp in the Marj Rahit plain north of Damascus.[14] Most of the Syrian junds backed Ibn al-Zubayr, with the exception of Jordan, whose dominant tribe was the Kalb.[66] With the critical support of the Kalb and its allied tribes, Marwan marched against al-Dahhak's larger army, while in Damascus city, a Ghassanid nobleman expelled al-Dahhak's partisans and brought the city under Marwan's authority.[14] In August, Marwan's forces routed the Qays and killed al-Dahhak at the Battle of Marj Rahit.[11][14] Marwan's rise had affirmed the power of the Quda'a tribal confederation, of which the Kalb was part,[67] and after the battle, it formed an alliance with the Qahtan confederation of Homs, forming the new super-tribe of Yaman.[68] The crushing Umayyad–Yamani victory at Marj Rahit led to the long-running Qays–Yaman blood feud.[69] The remnants of Qays rallied around Zufar ibn al-Harith al-Kilabi, who took over the fortress of Qarqisiya (Circesium) in Upper Mesopotamia, from which he led the tribal opposition to the Umayyads.[14] In a poem attributed to him, Marwan thanked the Yamani tribes for their support at Marj Rahit:

When I saw that the affair would be one of plunder, I made ready Ghassan and Kalb against them [the Qays],

And the Saksakīs [Kindites], men who would triumph, and Ṭayyi', who would insist on the striking of blows,

And the Qayn who would come weighed down with arms, and of Tanūkh a difficult and lofty peak.

[The enemy] will not seize the kingship unless by force, and if Qays approach, say, Keep away![70]

Although he was already recognized by the loyalist tribes at Jabiya, Marwan received ceremonial oaths of allegiance as caliph in Damascus in July or August.[63] He wed Yazid's widow and mother of Khalid, Umm Hashim Fakhita, thereby establishing a political link with the Sufyanids.[11] Wellhausen viewed the marriage as an attempt by Marwan to seize the inheritance of Yazid by becoming stepfather to his sons.[71] Marwan appointed the Ghassanid Yahya ibn Qays as the head of his shurta (security forces) and his own mawla Abu Sahl al-Aswad as his hajib (chamberlain).[72]

Despite his victory at Marj Rahit and the consolidation of Umayyad power in central Syria, Marwan's authority was not recognized in the rest of the Umayyads' former domains; with the help of Ibn Ziyad and Ibn Bahdal, Marwan undertook to restore Umayyad rule across the Caliphate with "energy and determination", according to Kennedy.[69] To Palestine he dispatched Rawh ibn Zinba, who forced the flight to Mecca of his rival for leadership of the Judham tribe, the pro-Zubayrid governor Natil ibn Qays.[73] Marwan also consolidated Umayyad rule in northern Syria, and the remainder of his reign was marked by attempts to reassert Umayyad authority.[11] By February/March 685, he secured his rule in Egypt with key assistance from the Arab tribal nobility of the provincial capital Fustat.[69] The province's pro-Zubayrid governor, Abd al-Rahman ibn Utba al-Fihri, was expelled and replaced with Marwan's son Abd al-Aziz.[11][69] Afterward, Marwan's forces led by Amr ibn Sa'id repulsed a Zubayrid expedition against Palestine launched by Ibn al-Zubayr's brother Mus'ab.[11][74] Marwan dispatched an expedition to the Hejaz led by the Quda'a commander Hubaysh ibn Dulja, which was routed at al-Rabadha east of Medina.[11][73] Meanwhile, Marwan sent his son Muhammad to check the Qaysi tribes in the middle Euphrates region.[69] By early 685, he dispatched an army led by Ibn Ziyad to conquer Iraq from the Zubayrids and the pro-Alids[11] (partisans of Caliph Ali and his household and the forerunners of the Shia sect of Islam).

Death and succession

[edit]After a reign of between six and ten months, depending on the source, Marwan died in the spring of 65 AH/685.[11] The precise date of his death is not clear from the medieval sources, with historians Ibn Sa'd, al-Tabari and Khalifa ibn Khayyat placing it on 29 Sha'ban/10 or 11 April, al-Mas'udi on 3 Ramadan/13 April and Elijah of Nisibis on 7 May.[11] Most early Muslim sources hold that Marwan died in Damascus, while al-Mas'udi holds that he died at his winter residence in al-Sinnabra near Lake Tiberias.[11] Although it is widely reported in the traditional Muslim sources that Marwan was killed in his sleep by Umm Hashim Fakhita in retaliation for a serious verbal insult to her honor by the caliph, most western historians dismiss the story.[75] Based on a report by al-Mas'udi,[76] Bosworth and others suspect Marwan succumbed to a plague afflicting Syria at the time of his death.[11]

Upon Marwan's return to Syria from Egypt in 685, he had designated his sons Abd al-Malik and Abd al-Aziz as his successors, in that order. He made the change after he reached al-Sinnabra and was informed that Ibn Bahdal recognized Amr ibn Sa'id as Marwan's successor-in-waiting.[77] He summoned and questioned Ibn Bahdal and ultimately demanded that he give allegiance to Abd al-Malik as his heir apparent.[77] By this, Marwan abrogated the arrangement reached at the Jabiya summit in 684,[11] re-instituting the principle of direct hereditary succession.[78] Abd al-Malik acceded to the caliphate without opposition from the previous designates, Khalid ibn Yazid and Amr ibn Sa'id.[11] Thereafter, hereditary succession became the standard practice of the Umayyad caliphs.[78]

Assessment

[edit]By making his family the foundation of his power, Marwan modeled his administration on that of Caliph Uthman, who extensively relied on his kinsmen, as opposed to Mu'awiya I, who largely kept them at arm's length.[79] To that end, Marwan ensured Abd al-Malik's succession as caliph and gave his sons Muhammad and Abd al-Aziz key military commands.[79] Despite the tumultuous beginnings, the "Marwanids" (descendants of Marwan) were established as the ruling house of the Umayyad realm.[67][79]

In the view of Bosworth, Marwan "was obviously a military leader and statesman of great skill and decisiveness amply endowed with the qualities of ḥilm [levelheadedness] and shrewdness, which characterised other outstanding members of the Umayyad clan".[11] His rise as caliph in Syria, a largely unfamiliar territory where he lacked a power-base, laid the foundations for Abd al-Malik's reign, which consolidated Umayyad rule for a further sixty-five years.[11] In the view of Madelung, Marwan's path to the caliphate was "truly high politics", the culmination of intrigues dating from his early career.[80] These included encouraging Uthman's empowerment of the Umayyads, becoming the "first avenger" of Uthman's assassination by murdering Talha, and privately undermining while publicly enforcing the authority of the Sufyanid caliphs of Damascus.[80]

Marwan was known to be gruff and lacking in social graces.[11] He suffered permanent injuries after a number of battle wounds.[11] His tall and emaciated appearance lent him the nickname khayt batil (gossamer-like thread).[11] In later anti-Umayyad Muslim tradition, Marwan was derided as tarid ibn tarid (outlawed son of an outlaw) in reference to his father al-Hakam's alleged exile to Ta'if by the Islamic prophet Muhammad and Marwan's expulsion from Medina by Ibn al-Zubayr. He was also referred to as abu al-jababira (father of tyrants) because his son and grandsons later inherited the caliphal throne.[11] In a number of sayings attributed to Muhammad, Marwan and his father are the subject of the Islamic prophet's foreboding, though Donner holds that much of these reports were likely conceived by Shia opponents of Marwan and the Umayyads in general.[81]

A number of reports cited by the medieval Islamic historians al-Baladhuri (d. 892) and Ibn Asakir (d. 1176) are indicative of Marwan's piety, such as the 9th-century historian al-Mada'ini's assertion that Marwan was among the best readers of the Qur'an and Marwan's own claim to have recited the Qur'an for over forty years before the Battle of Marj Rahit.[82] On the basis that many of his sons bore clearly Islamic names (as opposed to traditional Arabian names), Donner speculates Marwan may have indeed been "deeply religious" and "profoundly impressed" by the Qur'anic message to honor God and the prophets of Islam, including Muhammad.[83] Donner notes the difficulty of "achieving a sound assessment of Marwan", as with most Islamic leaders of his generation, due to an absence of archaeological and epigraphic documentation and the restriction of his biographical information to often polemical literary sources.[84]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The crown lands of Iraq were lands abandoned by the Sasanian royal family, the Iranian aristocracy and the Zoroastrian clergy during the Arab conquest of Sasanian Mesopotamia in the 630s. The lands were then designated as common property for the benefit of the Muslims in Kufa and Basra, the chief Arab garrison towns established in Iraq after the conquest. Their confiscation by Caliph Uthman as property of the central treasury in Medina provoked widespread consternation among the early Muslim settlers in Kufa, who derived significant revenue from the lands.[17]

- ^ Caliph Mu'awiya I's nomination of his own son Yazid I as his successor had been an unprecedented act in Islamic politics, marking a shift to hereditary rule from the earlier caliphs' elective or consultative form of succession. The move elicited charges in later Islamic tradition that the Umayyads transformed the office of the caliphate into a monarchy.[42][43]

References

[edit]- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 397.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Bosworth 1991, p. 621.

- ^ Della Vida & Bosworth 2000, p. 838.

- ^ Donner 1981, p. 77.

- ^ Watt 1986, p. 116.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Donner 2014, p. 110.

- ^ a b c Ahmed 2010, p. 111.

- ^ Ahmed 2010, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Ahmed 2010, p. 114.

- ^ Ahmed 2010, p. 90.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Bosworth 1991, p. 622.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 81.

- ^ a b c d Donner 2014, p. 106.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kennedy 2004, p. 91.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 92.

- ^ Della Vida & Khoury 2000, p. 947.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 68, 73.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 86–89.

- ^ Hinds 1972, pp. 457–459.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 127, 135.

- ^ a b c d e Hinds 1972, p. 457.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 136.

- ^ a b Madelung 1997, p. 137.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Anthony 2011, p. 112.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 52–53, 55–56.

- ^ a b Vaglieri 1965, p. 416.

- ^ a b Madelung 1997, p. 171.

- ^ Landau-Tasseron 1998, pp. 27–28, note 126.

- ^ a b Madelung 2000, p. 162.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 181, 190, 192 note 232, 196.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 235–236.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 77–80.

- ^ a b Hinds 1993, p. 265.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 104, 111.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 59–60, 161.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 136, 161.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 136.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 343–345.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 332.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 333.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 88.

- ^ Hawting 2000, pp. 13–14, 43.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 341–342.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 342–343.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 343.

- ^ Howard 1990, p. 2, note 11.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 142, 144–145.

- ^ a b c Kennedy 2004, p. 90.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 148.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 147.

- ^ a b Wellhausen 1927, p. 154.

- ^ Vaglieri 1971, p. 226.

- ^ Vaglieri 1971, p. 227.

- ^ Gibb 1960, p. 55.

- ^ Duri 2011, p. 23.

- ^ a b Duri 2011, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Duri 2011, pp. 23–25.

- ^ Duri 2011, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Biesterfeldt & Günther 2018, p. 952.

- ^ a b Wellhausen 1927, p. 182.

- ^ Rihan 2014, p. 103.

- ^ Rihan 2014, pp. 103–104.

- ^ a b Rihan 2014, p. 104.

- ^ a b Cobb 2001, p. 69.

- ^ Cobb 2001, pp. 69–70.

- ^ a b c d e Kennedy 2004, p. 92.

- ^ Hawting 1989, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 349.

- ^ Biesterfeldt & Günther 2018, p. 954.

- ^ a b Biesterfeldt & Günther 2018, p. 953.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 185.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 351.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 352.

- ^ a b Mayer 1952, p. 185.

- ^ a b Duri 2011, p. 25.

- ^ a b c Kennedy 2004, p. 93.

- ^ a b Madelung 1997, pp. 348–349.

- ^ Donner 2014, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Donner 2014, pp. 108, 114 notes 23–26.

- ^ Donner 2014, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Donner 2014, p. 105.

Sources

[edit]- Ahmed, Asad Q. (2010). The Religious Elite of the Early Islamic Ḥijāz: Five Prosopographical Case Studies. Oxford: University of Oxford Linacre College Unit for Prosopographical Research. ISBN 978-1-900934-13-8.

- Biesterfeldt, Hinrich; Günther, Sebastian (2018). The Works of Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-Yaʿqūbī (Volume 3): An English Translation. Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-35621-4.

- Bosworth, C.E. (1991). "Marwān I b. al-Ḥakam". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VI: Mahk–Mid. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 621–623. ISBN 978-90-04-08112-3.

- Cobb, Paul M. (2001). White Banners: Contention in 'Abbasid Syria, 750-880. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-4879-7.

- Della Vida, Giorgio Levi & Bosworth, C. E. (2000). "Umayya b. ʿAbd Shams". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume X: T–U. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 837–839. ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

- Della Vida, Giorgio Levi & Khoury, Raif Georges (2000). "ʿUthmān b. ʿAffān". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume X: T–U. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 946–949. ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

- Donner, Fred M. (1981). The Early Islamic Conquests. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05327-8.

- Donner, Fred M. (2014). "Was Marwan ibn al-Hakam the First 'Real' Muslim". In Savant, Sarah Bowen; de Felipe, Helena (eds.). Genealogy and Knowledge in Muslim Societies: Understanding the Past. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 105–114. ISBN 978-0-7486-4497-1.

- Duri, Abd al-Aziz (2011). Early Islamic Institutions: Administration and Taxation from the Caliphate to the Umayyads and ʿAbbāsids. Translated by Razia Ali. London and Beirut: I. B. Tauris and Centre for Arab Unity Studies. ISBN 978-1-84885-060-6.

- Gibb, H. A. R. (1960). "ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Zubayr". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 54–55. OCLC 495469456.

- Hawting, G. R., ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XX: The Collapse of Sufyānid Authority and the Coming of the Marwānids: The Caliphates of Muʿāwiyah II and Marwān I and the Beginning of the Caliphate of ʿAbd al-Malik, A.D. 683–685/A.H. 64–66. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-855-3.

- Hawting, Gerald R. (2000). The First Dynasty of Islam: The Umayyad Caliphate AD 661–750 (Second ed.). London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24072-7.

- Hinds, Martin (October 1972). "The Murder of the Caliph 'Uthman". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 13 (4): 450–469. doi:10.1017/S0020743800025216. JSTOR 162492. S2CID 159763369.

- Hinds, M. (1993). "Muʿāwiya I b. Abī Sufyān". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 263–268. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Howard, I. K. A., ed. (1990). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XIX: The Caliphate of Yazīd ibn Muʿāwiyah, A.D. 680–683/A.H. 60–64. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0040-1.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- Landau-Tasseron, Ella, ed. (1998). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXXIX: Biographies of the Prophet's Companions and their Successors: al-Ṭabarī's Supplement to his History. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2819-1.

- Madelung, Wilferd (1997). The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56181-7.

- Madelung, W. (2000). "Ṭalḥa". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume X: T–U. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 161–162. ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

- Mayer, L. A. (1952). "As-Sinnabra". Israel Exploration Journal. 2 (3): 183–187. JSTOR 27924483.

- Rihan, Mohammad (2014). The Politics and Culture of an Umayyad Tribe: Conflict and Factionalism in the Early Islamic Period. London and New York: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78076-564-8.

- Vaglieri, L. Veccia (1965). "Al-Djamal". In Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 414–416. OCLC 495469475.

- Vaglieri, L. Veccia (1971). "Al-Ḥarra". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume III: H–Iram. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 226–227. OCLC 495469525.

- Watt, W. M. (1986). "Kināna". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume V: Khe–Mahi. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 116. ISBN 978-90-04-07819-2.

- Wellhausen, Julius (1927). The Arab Kingdom and Its Fall. Translated by Margaret Graham Weir. Calcutta: University of Calcutta. OCLC 752790641.

- Anthony, Sean (25 November 2011). The Caliph and the Heretic: Ibn Saba' and the Origins of Shi'ism. BRILL. ISBN 978-900420930-5.