Gerry Adams

Gerry Adams | |

|---|---|

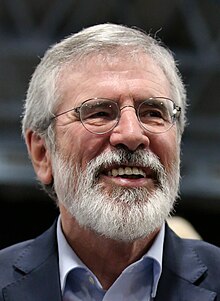

Adams in 2018 | |

| President of Sinn Féin | |

| In office 13 November 1983 – 10 February 2018 | |

| Vice President |

|

| Preceded by | Ruairí Ó Brádaigh |

| Succeeded by | Mary Lou McDonald |

| Leader of Sinn Féin in Dáil Éireann | |

| In office 9 March 2011 – 10 February 2018 | |

| Preceded by | Caoimhghín Ó Caoláin |

| Succeeded by | Mary Lou McDonald |

| Teachta Dála for Louth | |

| In office February 2011 – February 2020 | |

| Member of the Legislative Assembly for Belfast West | |

| In office 25 June 1998 – 7 December 2010 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Pat Sheehan |

| Member of Parliament for Belfast West | |

| In office 1 May 1997 – 26 January 2011 | |

| Preceded by | Joe Hendron |

| Succeeded by | Paul Maskey |

| In office 9 June 1983 – 16 March 1992 | |

| Preceded by | Gerry Fitt |

| Succeeded by | Joe Hendron |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Gerard Adams 6 October 1948 Belfast, Northern Ireland |

| Political party | Sinn Féin |

| Spouse |

Collette McArdle (m. 1971) |

| Children | 1 |

| Parent |

|

| Education | St. Mary's CBS, Belfast |

| Website | sinnfein |

Gerard Adams (Irish: Gearóid Mac Ádhaimh;[1] born 6 October 1948) is an Irish republican politician who was the president of Sinn Féin between 13 November 1983 and 10 February 2018, and served as a Teachta Dála (TD) for Louth from 2011 to 2020.[2][3] From 1983 to 1992 and from 1997 to 2011, he followed the policy of abstentionism as a Member of Parliament (MP) of the British Parliament for the Belfast West constituency.

Adams first became involved in Irish republicanism in the late 1960s, and had been an established figure in Irish activism for more than a decade before his 1983 election to Parliament. In 1984, Adams was seriously wounded in an assassination attempt by several gunmen from the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), including John Gregg.[4] From the late 1980s onwards, he was an important figure in the Northern Ireland peace process, entering into talks initially with Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) leader John Hume and then subsequently with the Irish and British governments.[5] In 1986, he convinced Sinn Féin to change its traditional policy of abstentionism towards the Oireachtas, the parliament of the Republic of Ireland. In 1998, it also took seats in the power-sharing Northern Ireland Assembly. In 2005, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) stated that its armed campaign was over and that it was exclusively committed to peaceful politics.[6]

Adams has often been accused of being a member of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) leadership in the 1970s and 80s, though he consistently denied any involvement in the organisation. In 2014, he was held for four days by the Police Service of Northern Ireland for questioning in connection with the 1972 abduction and murder of Jean McConville.[7][8] He was released without charge and a file was sent to the Public Prosecution Service for Northern Ireland,[9] which later stated there was insufficient evidence to charge him.[10][11][12] Adams announced in November 2017 that he would step down as leader of Sinn Féin in 2018, and that he would not stand for re-election to his seat in Dáil Éireann in 2020.[13] He was succeeded by Mary Lou McDonald at a special ardfheis (party conference) on 10 February 2018.[14]

Early life

[edit]Adams was born in the Ballymurphy district of Belfast on 6 October 1948.[15][16] His parents, Anne (née Hannaway) and Gerry Adams Sr., came from republican backgrounds.[16] His grandfather, also named Gerry Adams, was a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) during the Irish War of Independence. Two of his uncles, Dominic and Patrick Adams, had been interned by the governments in Belfast and Dublin.[17] In J. Bowyer Bell's book The Secret Army,[18] Bell states that Dominic was a senior figure in the Irish Republican Army (IRA) of the mid-1940s. Gerry Adams Sr. joined the IRA at age 16. In 1942, he participated in an IRA ambush on a Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) patrol but was shot, arrested and sentenced to eight years' imprisonment.[15] Adams's maternal great-grandfather, Michael Hannaway, was also a member of the IRB during its bombing campaign in England in the 1860s and 1870s.[19] Michael's son, Billy, was election agent for Éamon de Valera at the 1918 Irish general election in West Belfast.

Adams attended St Finian's Primary School on Falls Road, where he was taught by La Salle brothers. Having passed the eleven-plus exam in 1960, he attended St Mary's Christian Brothers Grammar School. He left St Mary's with six O-levels and worked in bars. He was increasingly involved in the Irish republican movement, joining Sinn Féin and Fianna Éireann in 1964, after being radicalised by the Divis Street riots during that year's general election campaign.[20]

Early political career

[edit]

In the late 1960s, a civil rights campaign developed in Northern Ireland. Adams was an active supporter and joined the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association in 1967.[20] However, the civil rights movement was met with violence from loyalist counter-demonstrations and the RUC. In August 1969, the Northern Ireland riots resulted in violence in Belfast, Derry and elsewhere. British troops were called in at the request of the Government of Northern Ireland.

Adams was active in rioting at this time and later became involved in the republican movement. In August 1971, internment was reintroduced to Northern Ireland under the Special Powers Act 1922. Adams was captured by British soldiers in March 1972 and in a Belfast Telegraph report on Adams' capture he was said to be "one of the most wanted men in Belfast".[21][22] Adams was interned on HMS Maidstone, but on the Provisional IRA's insistence was released in June to take part in secret, but abortive talks in London.[20] The IRA negotiated a short-lived truce with the British government and an IRA delegation met with British Home Secretary William Whitelaw at Cheyne Walk in Chelsea. The delegation included Adams, Martin McGuinness, Sean Mac Stiofain (IRA Chief of Staff), Daithi O'Conaill, Seamus Twomey, Ivor Bell and Dublin solicitor Myles Shevlin.[23] Adams was re-arrested in July 1973 and interned at the Maze prison. After taking part in an IRA-organised escape attempt, he was sentenced to a period of imprisonment. During this time, he wrote articles in the paper An Phoblacht under the by-line "Brownie", where he criticised the strategy and policy of Sinn Féin president Ruairí Ó Brádaigh and Billy McKee, the IRA's officer commanding in Belfast. He was also highly critical of a decision taken by McKee to assassinate members of the rival Official IRA, who had been on ceasefire since 1972.[24] In 2020, the UK Supreme Court quashed Adams' convictions for attempting to escape on Christmas Eve in 1973 and again in July 1974.[25]

In 1977, Ballymurphy priest Des Wilson (who had officiated at Adams's wedding) assisted with an early attempt by Adams to open channels to dissident unionists. He helped set up meeting with Desmond Boal QC, a unionist barrister who had been first chairman of Ian Paisley's Democratic Unionist Party.[26][27] At the time, Boal was co-operating with Seán MacBride as joint mediator in confidential negotiations between the Provisional IRA and the Ulster Volunteer Force about a federal settlement for Ireland.[28] A short time later, Wilson drove Adams to a meeting with John McKeague, founding member of the Red Hand Commando, then flirting with the idea of an independent Ulster. Inasmuch as they were "frank" , Adams found the meetings "constructive", but could find no common political ground.[29] Wilson was of the view that Adams was "one of the very few people who could actually bring a military campaign into a political campaign".[30]

IRA membership allegations

[edit]Adams has stated repeatedly that he has never been a member of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA).[31] However, journalists such as Ed Moloney, Peter Taylor and Mark Urban, and historian Richard English have all named Adams as part of the IRA leadership since the 1970s.[32][33][34][35]

Moloney and Taylor state Adams became the IRA's Chief of Staff following the arrest of Seamus Twomey in early December 1977, remaining in the position until 18 February 1978 when he, along with twenty other republican suspects, was arrested following the La Mon restaurant bombing.[36][37] He was charged with IRA membership and remanded to Crumlin Road Gaol.[38] He was released seven months later when the Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland Robert Lowry ruled there was insufficient evidence to proceed with the prosecution.[38][39] Moloney and English state Adams had been a member of the IRA Army Council since 1977, remaining a member until 2005 according to former Irish Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform Michael McDowell.[40][34][41]

2014 arrest

[edit]On 30 April 2014, Adams was arrested by detectives from the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) Serious Crime Branch, under the Terrorism Act 2000, in connection with the murder of Jean McConville in 1972.[42] He had previously voluntarily arranged to be interviewed by police regarding the matter,[43] and maintained he had no involvement.[44] Fellow Sinn Féin politician Alex Maskey stated that the timing of the arrest, "three weeks into an election", was evidence of a "political agenda [...] a negative agenda" by the PSNI.[45] McConville's family had campaigned for the arrest of Adams for the murder.[46] McConville's son Michael said that his family did not think the arrest of Adams would ever happen, and were glad that the arrest took place. Adams was released without charge after four days in custody a file was sent to the Public Prosecution Service, which would decide if criminal charges should be brought.[47][48][49]

At a press conference after his release, Adams criticised the timing of his arrest, reiterated Sinn Féin's support for the PSNI and said: "The IRA is gone. It is finished."[50] Adams denied that he had any involvement in the murder or was ever a member of the IRA,[9][44][51] and said the allegations came from "enemies of the peace process".[9] On 29 September 2015 the Public Prosecution Service announced Adams would not face charges, due to insufficient evidence,[52] as had been expected ever since a BBC report dated 6 May 2014 (2 days after the BBC reported his release),[11] which was widely repeated elsewhere.[12]

Rise in Sinn Féin

[edit]

In 1978, Adams became joint vice-president of Sinn Féin and a key figure in directing a challenge to the Sinn Féin leadership of President Ruairí Ó Brádaigh and joint vice-president Dáithí Ó Conaill. The 1975 IRA-British truce is often viewed as the event that began the challenge to the original Provisional Sinn Féin leadership, which was dominated by southerners like Ó Brádaigh and Ó Conaill.

One of the reasons that the Provisional IRA and Provisional Sinn Féin were founded, in December 1969 and January 1970, respectively, was that people like Ó Brádaigh, Ó Conaill and McKee opposed participation in constitutional politics. The other reason was the failure of the Cathal Goulding leadership to provide for the defence of Irish nationalist areas during the 1969 Northern Ireland riots. When, at the December 1969 IRA convention and the January 1970 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis, the delegates voted to participate in the Dublin (Leinster House), Belfast (Stormont) and London (Westminster) parliaments, the organisations split. Adams, who had joined the republican movement in the early 1960s, sided with the Provisionals.

In the Maze prison in the mid-1970s, writing under the pseudonym "Brownie" in Republican News, Adams called for increased political activity among republicans, especially at local level.[53] The call resonated with younger Northern people, many of whom had been active in the Provisional IRA but few of whom had been active in Sinn Féin. In 1977, Adams and Danny Morrison drafted the address of Jimmy Drumm at the annual Wolfe Tone commemoration at Bodenstown. The address was viewed as watershed in that Drumm acknowledged that the war would be a long one and that success depended on political activity that would complement the IRA's armed campaign. For some,[who?] this wedding of politics and armed struggle culminated in Danny Morrison's statement at the 1981 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis in which he asked "Who here really believes we can win the war through the ballot box? But will anyone here object if, with a ballot paper in one hand and the Armalite in the other, we take power in Ireland?" For others, however, the call to link political activity with armed struggle had already been defined in Sinn Féin policy and in the presidential addresses of Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, but this had not resonated with young Northerners.[54]

Even after the election of Bobby Sands as MP for Fermanagh and South Tyrone, a part of the mass mobilisation associated with the 1981 Irish Hunger Strike by republican prisoners in the H blocks of the Maze Prison, Adams was cautious that the level of political involvement by Sinn Féin could lead to electoral embarrassment. Charles Haughey, the Taoiseach of Ireland, called an election for June 1981. At an Ard Chomhairle meeting, Adams recommended that they contest only four constituencies which were in border counties. Instead, H-Block/Armagh candidates contested nine constituencies and elected two TDs. This, along with the election of Sands, was a precursor to an electoral breakthrough in elections in 1982 to the 1982 Northern Ireland Assembly.[55] Adams, Danny Morrison, Martin McGuinness, Jim McAllister and Owen Carron were elected as abstentionists. The Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) had announced before the election that it would not take any seats and so its 14 elected representatives also abstained from participating in the Assembly and it was a failure. The 1982 election was followed by the 1983 Westminster election, in which Sinn Féin's vote increased and Adams was elected, as an abstentionist, as MP for Belfast West. It was in 1983 that Ruairí Ó Brádaigh resigned as President of Sinn Féin and was succeeded by Adams.

In 1983, Adams was elected president of Sinn Féin and became the first Sinn Féin MP elected to the British House of Commons since Phil Clarke and Tom Mitchell in the mid-1950s.[20] Following his election as MP for Belfast West, the British government lifted a ban on his travelling to Great Britain. In line with Sinn Féin policy, he refused to take his seat in the House of Commons.[56]

Assassination attempt by the UDA

[edit]On 14 March 1984 in central Belfast, Adams was seriously wounded in an assassination attempt when several Ulster Defence Association (UDA) gunmen fired about 20 shots into the car in which he was travelling. He was hit in the neck, shoulder and arm. He was rushed to the Royal Victoria Hospital, where he underwent surgery to remove three bullets. John Gregg and his team were apprehended almost immediately by a British Army patrol that opened fire on them before ramming their car.[57] The attack had been known in advance by security forces due to a tip-off from informants within the UDA; Adams and his co-passengers had survived in part because RUC officers, acting on the informants' information, had replaced much of the ammunition in the UDA's Rathcoole weapons dump with low-velocity bullets.[58] Some, including Adams himself, still have unanswered questions about the RUC's actions prior to the shooting.[59] An Ulster Defence Regiment NCO subsequently received the Queen's Gallantry Medal for chasing and arresting an assailant.[60][full citation needed]

President of Sinn Féin

[edit]Many republicans had long claimed that the only legitimate Irish state was the Irish Republic declared in the 1916 Proclamation of the Republic. In their view, the legitimate government was the IRA Army Council, which had been vested with the authority of that Republic in 1938 (prior to the Second World War) by the last remaining anti-Treaty deputies of the Second Dáil. In his 2005 speech to the Sinn Féin Ard Fheis in Dublin, Adams explicitly rejected this view. "But we refuse to criminalise those who break the law in pursuit of legitimate political objectives. ... Sinn Féin is accused of recognising the Army Council of the IRA as the legitimate government of this island. That is not the case. [We] do not believe that the Army Council is the government of Ireland. Such a government will only exist when all the people of this island elect it. Does Sinn Féin accept the institutions of this state as the legitimate institutions of this state? Of course we do."[61]

As a result of this non-recognition, Sinn Féin had abstained from taking any of the seats they won in the British or Irish parliaments. At its 1986 Ard Fheis, Sinn Féin delegates passed a resolution to amend the rules and constitution that would allow its members to sit in the Dublin parliament. At this, Ruairí Ó Brádaigh led a small walkout, just as he and Sean Mac Stiofain had done sixteen years earlier with the creation of Provisional Sinn Féin.[62][63][64][65] This minority, which rejected dropping the policy of abstentionism, now distinguishes itself from Sinn Féin by using the name Republican Sinn Féin, and maintains that they are the true Sinn Féin.

Adams' leadership of Sinn Féin was supported by a Northern-based cadre that included people like Danny Morrison and Martin McGuinness. Over time, Adams and others pointed to republican electoral successes in the early and mid-1980s, when hunger strikers Bobby Sands and Kieran Doherty were elected to the British House of Commons and Dáil Éireann respectively, and they advocated that Sinn Féin become increasingly political and base its influence on electoral politics rather than paramilitarism. The electoral effects of this strategy were shown later by the election of Adams and McGuinness to the House of Commons.

Voice ban

[edit]Adams's prominence as an Irish republican leader was increased by the 1988–1994 British broadcasting voice restrictions,[66] which were imposed by British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher to "starve the terrorist and the hijacker of the oxygen of publicity on which they depend".[67] Thatcher was moved to act after BBC interviews of Martin McGuinness and Adams had been the focus of a row over an edition of After Dark, a proposed Channel 4 discussion programme which in the event was never made.[68] While the ban covered 11 Irish political parties and paramilitary organisations, in practice it mostly affected Sinn Féin, the most prominent of these bodies.[69]

A similar ban, known as Section 31, had been law in the Republic of Ireland since the 1970s. However, media outlets soon found ways around the bans. In the UK, this was initially by the use of subtitles, but later and more often by an actor reading words accompanied by video footage of the banned person speaking. Actors who voiced Adams included Stephen Rea and Paul Loughran.[70][71] This loophole could not be used in the Republic, as word-for-word broadcasts were not allowed.[72] Instead, the banned speaker's words were summarised by the newsreader, over video of them speaking.

These bans were lampooned in cartoons and satirical TV shows, such as Spitting Image, and in The Day Today, and were criticised by freedom of speech organisations and media personalities, including BBC Director General John Birt and BBC foreign editor John Simpson. The Republic's ban was allowed to lapse in January 1994, and the British ban was lifted by Prime Minister John Major in September 1994.[73][74]

Movement into mainstream politics

[edit]

Sinn Féin continued its policy of refusing to sit in the Westminster Parliament after Adams won the Belfast West constituency. He lost his seat to Joe Hendron of the SDLP in the 1992 general election,[75] regaining it at the following 1997 election. Under Adams, Sinn Féin moved away from being a political voice of the Provisional IRA to becoming a professionally organised political party in both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

SDLP leader John Hume identified the possibility that a negotiated settlement might be possible and began secret talks with Adams in 1988. These discussions led to unofficial contacts with the British Northern Ireland Office under the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Peter Brooke, and with the government of the Republic under Charles Haughey – although both governments maintained in public that they would not negotiate with terrorists.[citation needed] These talks provided the groundwork for what was later to be the Belfast Agreement, preceded by the milestone Downing Street Declaration and the Joint Framework Document.[76]

These negotiations led to the IRA ceasefire in August 1994. Taoiseach Albert Reynolds, who had replaced Haughey and who had played a key role in the Hume/Adams dialogue through his Special Advisor Martin Mansergh, regarded the ceasefire as permanent. However, the slow pace of developments contributed in part to the (wider) political difficulties of the British government of John Major. His consequent reliance on Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) votes in the House of Commons led to him agreeing with the UUP demand to exclude Sinn Féin from talks until the IRA had decommissioned its weapons. Sinn Féin's exclusion led the IRA to end its ceasefire and resume its campaign.[77]

After the 1997 United Kingdom general election, the new Labour government had a majority in the House of Commons and was not reliant on unionist votes. The subsequent dropping of the insistence led to another IRA ceasefire, as part of the negotiations strategy, which saw teams from the British and Irish governments, the UUP, the SDLP, Sinn Féin, and representatives of loyalist paramilitary organisations, under the chairmanship of former United States Senator George Mitchell, produce the Good Friday Agreement in 1998.[16] Under the Agreement, structures were created reflecting the Irish and British identities of the people of Ireland, creating a British-Irish Council and a Northern Ireland Legislative Assembly.[78]

Articles 2 and 3 of the Constitution of Ireland of the Republic's constitution, which claimed sovereignty over all of Ireland, were reworded, and a power-sharing Executive Committee was provided for. As part of their deal, Sinn Féin agreed to abandon its abstentionist policy regarding a "six-county parliament", as a result taking seats in the new Stormont-based Assembly and running the education and health and social services ministries in the power-sharing government.

Sinn Féin in government

[edit]

On 15 August 1998, four months after the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, the Omagh bombing by the Real IRA, killed 29 people and injured 220, from many communities. Adams said in reaction to the bombing "I am totally horrified by this action. I condemn it without any equivocation whatsoever."[79] Prior to this, Adams had not used the word "condemn" in relation to IRA or their splinter groups' actions.[79][80]

When Sinn Féin came to nominate its two ministers to the Northern Ireland Executive, for tactical reasons the party, like the SDLP and the DUP, chose not to include its leader among its ministers. When later the SDLP chose a new leader, it selected one of its ministers, Mark Durkan, who then opted to remain in the committee.

Adams was re-elected to the Northern Ireland Assembly on 8 March 2007, and on 26 March 2007, he met with DUP leader Ian Paisley face-to-face for the first time. These talks led to the St Andrews Agreement, which brought about the return of the power-sharing Executive in Northern Ireland.[81]

In January 2009, Adams attended the United States presidential inauguration of Barack Obama as a guest of US Congressman Richard Neal.[82]

Election to Dáil Éireann

[edit]

On 6 May 2010, Adams was re-elected as MP for West Belfast, garnering 71.1% of the vote.[83] In 2010, Adams announced that he would be seeking election as a TD (member of Irish Parliament) for the constituency of Louth at the 2011 Irish general election.[84] He subsequently resigned his West Belfast Assembly seat on 7 December 2010.[85]

Following the announcement of the 2011 Irish general election, Adams resigned his seat at the House of Commons.[86][87] He was elected to the Dáil, topping the Louth constituency poll with 15,072 (21.7%) first preference votes.[88] He succeeded Caoimhghín Ó Caoláin as Sinn Féin parliamentary leader in Dáil Éireann.[89] In December 2013, Adams was a member of the Guard of Honour at Nelson Mandela's funeral.[90][91]

On 19 May 2015, while on an official royal trip to Ireland, Prince Charles shook Adams' hand in what was described as a highly symbolic gesture of reconciliation. The meeting, described as "historic", took place in Galway.[92]

In September 2017, Adams said he would allow his name to go forward for a one-year term as president of Sinn Féin at the November ardfheis, at which point Sinn Féin would begin a "planned process of generational change, including [Adams'] own future intentions". This resulted in speculation in the Irish and British media that Adams was preparing to stand down as party leader, and that he might run for President of Ireland in the next election.[93][94][95] At the ardfheis on 18 November, Adams was re-elected for another year as party president, but announced that he would step down at some point in 2018, and would not seek re-election as TD for Louth.[13]

End of Sinn Féin presidency

[edit]

Adams' presidency of Sinn Féin ended on 10 February 2018, with his stepping down and the election of Mary Lou McDonald as the party's new president.[96]

On 13 July 2018, a home-made bomb was thrown at Adams' home in West Belfast, damaging a car parked in his driveway. Adams escaped injury and claimed that his two grandchildren were standing in the driveway only ten minutes before the blast. Another bomb was set off that same evening at the nearby home of former IRA volunteer and Sinn Féin official Bobby Storey. In a press conference the following day, Adams said he thought the attacks were linked to the riots in Derry, and asked that those responsible "come and sit down" and "give us the rationale for this action".[97][98]

Personal life

[edit]| Part of the Politics series |

| Republicanism |

|---|

|

|

In 1971, Adams married Collette McArdle.[99] They have a son named Gearoid (born 1973),[100] who has played Gaelic football for Antrim GAA senior men's team and became its assistant manager in 2012.[101]

In October 2013, Adams' brother Liam was found guilty of 10 offences, including rape and gross indecency committed against his own daughter.[102][103] After the allegations of abuse were first made public in a 2009 UTV programme, Gerry Adams alleged that his father had subjected family members to emotional, physical, and sexual abuse.[104][105] On 27 November 2013, Liam was jailed for 16 years.[106] Liam died of pancreatic cancer in February 2019 at the age of 63 while in Maghaberry Prison.[107]

On 1 May 2016, Adams sparked controversy by tweeting, "Watching Django Unchained—A Ballymurphy Nigger!"[108] The tweet was criticised and subsequently deleted, with Adams apologising for the use of "nigger" the next day at Sinn Féin's Connolly House headquarters in Belfast. The tweet was widely reported in Irish,[109] British,[110] and American media.[111][112] Adams said, "I stand over the context and main point of my tweet, which were the parallels between people in struggle. Like African Americans, Irish nationalists were denied basic rights. I have long been inspired by Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, and Malcolm X, who stood up for themselves and for justice."[113] On 4 May, he said, "The whole thing was to make a political point. If I had left that word out, would the tweet have gotten any attention? ... I was paralleling the experiences of the Irish, not just in recent times but through the penal days when the Irish were sold as slaves, through the Cromwellian period."[114] He was criticised for perpetuating what has been called the "Irish slaves myth", by equating the indentured servitude of the Irish with the chattel slavery of African Americans.[115][116][117]

Media portrayals

[edit]Adams has been portrayed in a number of films, TV series, and books:

- 1999 – The Marching Season, a spy fiction novel by Daniel Silva.

- 2004 – film Omagh, with actor Jonathan Ryan, a dramatisation of the 1998 Omagh bombing and its aftermath.

- 2010 – TV film Mo, with actor John Lynch, the story of Mo Mowlam and the Good Friday Agreement.

- 2012 – The Cold Cold Ground, a crime novel by Adrian McKinty; Adams is interviewed by the book's main character after an associate is found murdered.

- 2016 – film The Journey, with actor Ian Beattie.[118]

- 2017 – film The Foreigner, with actor Pierce Brosnan playing a former IRA leader who resembles Adams.[119]

Published works

[edit]- Falls Memories, 1982

- The Politics of Irish Freedom, 1986

- A Pathway to Peace, 1988

- An Irish Voice: The Quest for Peace

- Cage Eleven, 1990, Brandon Books, ISBN 978-0-86322-114-9

- The Street and Other Stories, 1993, Brandon Books, ISBN 978-0-86322-293-1

- Free Ireland: Towards a Lasting Peace, 1995

- Before the Dawn: An Autobiography, 1996, Brandon Books, ISBN 978-0-434-00341-9

- Selected Writings

- Who Fears to Speak...?, 2001 (Original Edition 1991), Beyond the Pale Publications, ISBN 978-1-900960-13-7

- An Irish Journal, 2001, Brandon Books, ISBN 978-0-86322-282-5

- Hope and History: Making Peace in Ireland, 2003, Brandon Books, ISBN 978-0-86322-330-3

- A Farther Shore, 2005, Random House

- The New Ireland: A Vision For The Future, 2005, Brandon Books, ISBN 978-0-86322-344-0

- An Irish Eye, 2007, Brandon Books, ISBN 978-0-86322-370-9

- My Little Book of Tweets, 2016, Mercier Press, ISBN 978-1-78117-449-4

References

[edit]- ^ "Cairt Chearta do Chách" (in Irish). Archived from the original on 18 November 2007. Retrieved 30 November 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) Sinn Féin press release, 26 January 2004. - ^ "Gerry Adams". Oireachtas Members Database. Archived from the original on 7 November 2018. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- ^ "Gerry Adams". ElectionsIreland.org. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ^ "1984: Sinn Fein leader shot in street attack". BBC: On This Day. 14 March 1984. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- ^ "Irish Genealogy, Customs & Roots". IrishCentral.com. Archived from the original on 6 January 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ "Full text: IRA statement". The Guardian. London. 28 July 2005. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- ^ Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams held over Jean McConville murder Archived 21 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ Gerry Adams remains in custody over McConville murder Archived 1 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, 1 May 2014.

- ^ a b c "Timing of arrest wrong says Adams". BBC News. 4 May 2014. Archived from the original on 27 July 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ "Jean McConville murder: Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams will not face Disappeared charges" Archived 20 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News, 29 September 2015.

- ^ a b "Gerry Adams denies McConville son 'backlash threat'". BBC. 6 May 2014. Archived from the original on 11 May 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

BBC News understands there was insufficient evidence to charge Mr Adams with any offence.

- ^ a b Anthony Bond, Sam Adams (6 May 2014). ""Insufficient evidence" to 'pursue prosecution of Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams'". Daily Mirror. Archived from the original on 7 May 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

No charges would be brought against Mr Adams unless significant new evidence comes to light, according to reports ... There is "insufficient evidence" to pursue a prosecution against Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams in relation to the 1972 murder of Jean McConville, according to reports. The BBC said it understood that no charges would be brought against Mr Adams unless significant new evidence comes to light.

- ^ a b Doyle, Kevin (18 November 2017). "Gerry Adams to step down as Sinn Féin leader in 2018". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 19 November 2017. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- ^ "Mary Lou McDonald confirmed as new leader of Sinn Féin". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ a b "Gerry Adams: Profile of Sinn Féin leader". BBC News. 20 November 2017. Archived from the original on 10 March 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- ^ a b c "Gerry Adams". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ "Profile: Gerry Adams". BBC News. 20 November 2017. Archived from the original on 21 January 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ J. Bowyer Bell, The Secret Army: The IRA 1916 (Irish Academy Press).

- ^ Moloney 2002, p. 38.

- ^ a b c d Lalor, Brian, ed. (2003). The Encyclopaedia of Ireland. Dublin, Ireland: Gill & Macmillan. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-7171-3000-9.

- ^ "Troops catch three top Provisionals", The Belfast Telegraph, 14 March 1972.

- ^ "Detained trio named", The Belfast Telegraph, 15 March 1972.

- ^ O'Brien, Brendan (1999). The long war: the IRA and Sinn Féin, Brendan O'Brien, p169. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0597-3. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ Moloney 2002, pp. 166–168.

- ^ Ng, Kate (14 May 2020). "Gerry Adams wins Supreme Court appeal against convictions over prison break bids". The Independent. Archived from the original on 17 May 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ "Derry City Cemetery Series: Desmond Boal, the DUP founder and unionist MP who defended dozens of republicans in court". www.derrynow.com. 11 July 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ Ryder, Chris (7 May 2015). "Desmond Boal obituary". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ Maune, Patrick (2022). "Boal, Desmond Norman Orr | Dictionary of Irish Biography". www.dib.ie. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ Sharrock & Devenport 1997, p. 155.

- ^ Sharrock & Devenport 1997, p. 462.

- ^ Rosie Cowan (1 October 2002). "Adams denies IRA links as book calls him a genius". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2007.

- ^ Moloney 2002, p. 140.

- ^ Taylor 1997, p. 140.

- ^ a b English, Richard (2003). Armed Struggle: The History of the IRA. Pan Books. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-330-49388-8.

- ^ Urban, Mark (1993). Big Boys' Rules: SAS and the Secret Struggle Against the IRA. Faber and Faber. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-571-16809-5.

- ^ Moloney 2002, pp. 171–172.

- ^ Taylor 1997, p. 201.

- ^ a b Moloney 2002, p. 173.

- ^ Taylor 1997, pp. 201–202.

- ^ Moloney 2002, p. 380.

- ^ "SF members 'leave army council'". 29 July 2005. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ O'Connell, Hugh (2 May 2014). "The PSNI have been granted an extra 48 hours to question Gerry Adams". thejournal.ie. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ McDonald, Henry (30 April 2014). "Sinn Féin president Gerry Adams held over 1972 Jean McConville killing". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 1 May 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams held over Jean McConville murder". BBC News. London. 30 April 2014. Archived from the original on 30 April 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ Beaton, Connor (30 April 2014). "SF MLA: Adams arrest 'negative PSNI agenda'". The Targe. Archived from the original on 7 October 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams arrested over murder of widowed mother abducted in 1972 Archived 20 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams held over Jean McConville murder Archived 24 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. 30 April 2014.

- ^ Shadow of Jean McConville murder still hangs over Gerry Adams and Sinn Fein Archived 5 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine Irish Independent, 5 May 2014.

- ^ "Adams released without charge". BBC. 4 May 2014. Archived from the original on 4 May 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- ^ "BBC News – Gerry Adams freed in Jean McConville murder inquiry". BBC News. 4 May 2014. Archived from the original on 27 July 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ "Gerry Adams denies McConville son 'backlash threat'". BBC. 6 May 2014. Archived from the original on 11 May 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

The Sinn Fein president was questioned for four days in connection with the murder of Jean McConville and membership of the IRA.He has strongly denied all those allegations. ... He again said he was innocent of any involvement in Mrs McConville's murder.

- ^ "Gerry Adams will not face charges over Jean McConville murder". The Guardian. 29 September 2015. Archived from the original on 6 June 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "Sinn Féin: where does the money come from?". Irish Independent. 19 June 2004. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015.

- ^ Robert White, Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, The Life and Politics of an Irish Revolutionary, pp. 258–59.

- ^ Nicholas Whyte. "Northern Ireland Assembly Elections 1982". Ark.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 13 February 2007. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- ^ "Gerry Adams Fast Facts". CNN. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ McDonald & Cusack 2004, p. 129.

- ^ McDonald & Cusack 2004, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Kevin Maguire (14 December 2006). "Adams wants 1984 shooting probe". BBC. Archived from the original on 27 January 2007. Retrieved 22 March 2007.

- ^ Potter, p. 268.

- ^ Adams, Gerry, Speech to 2005 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis. Archived 8 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine CAIN Web Service.

- ^ Taylor 1997, p. 291.

- ^ Anderson, Brendan (2002). Joe Cahill: A Life in the IRA. O'Brien Press. p. 340. ISBN 978-0-86278-836-0.

- ^ O'Brien, Brendan (1999). The Long War: The IRA and Sinn Féin. O'Brien Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-86278-606-9.

- ^ Bishop, Patrick; Mallie, Eamonn (1987). The Provisional IRA. Corgi Books. p. 448. ISBN 978-0-552-13337-1.

- ^ The 'broadcast ban' on Sinn Fein Archived 16 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, 5 April 2005.

- ^ Edgerton, Gary Quelling the "Oxygen of Publicity": British Broadcasting and "The Troubles" During the Thatcher Years, The Journal of Popular Culture, Volume 30, Issue 1, pp. 115–32.

- ^ Dubbing SF voices becomes the stuff of history Archived 17 March 2005 at the Wayback Machine, By Michael Foley The Irish Times, 17 September 1994.

- ^ FRANKEL, GLENN (18 November 1990). "Britain's Media Ban on Terrorist Groups Remains Controversial : Censorship: Voices of revered statesmen are silenced in history program broadcast to schoolchildren in Northern Ireland". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on 18 November 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ "Paul Loughran". Ulsteractors.com. 22 December 2011. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ^ Foy, Ken; Murphy, Cormac (24 January 2014). "Dolours Price, former IRA terrorist and ex-wife of actor Stephen Rea, dies of suspected overdose". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ^ "BBC News – Twenty years on: The lifting of the ban on broadcasting Sinn Féin". BBC News. 22 January 2014. Archived from the original on 15 April 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ "CAIN: Chronology of the Conflict 1994". Conflict Archive on the Internet. University of Ulster. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ^ "Britain Ends Broadcast Ban on Irish Extremists : Negotiations: Prime Minister Major also backs referendum on Northern Ireland's fate. Both moves indicate desire to move ahead on peace plan". Los Angeles Times. 17 September 1994. Archived from the original on 18 December 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ^ Cook, Bernard A. (27 January 2014). Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 9781135179328. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ Albert, Cornelia (2009). The Peacebuilding Elements of the Belfast Agreement and the Transformation of the Northern Ireland Conflict. Peter Lang. ISBN 9783631585917. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ "When peace almost died of exhaustion". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 4 October 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ "Good Friday Agreement | British-Irish history". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ a b "Sinn Féin condemnation 'unequivocal'". BBC. 16 August 1998. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ "Adams's condemnation further isolates dissidents". Irish Times. 17 August 1998. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ "May date for return to devolution". BBC. 26 March 2007. Archived from the original on 1 April 2007. Retrieved 26 March 2007.

- ^ 19/Jan/2009 Barack Obama inauguration: Gerry Adams to attend ceremony The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ "Election 2010". BBC. 7 May 2010. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ "Adams to contest Co Louth seat for SF in next election". The Irish Times. 14 November 2010. Archived from the original on 22 November 2010. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ^ Northern Ireland Assembly Information Office. "NI Assembly membership, note 17". Niassembly.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 17 November 2007. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- ^ "Gerry Adams quits Westminster seat". The Belfast Telegraph. 20 January 2011. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ "Gerry Adams resigns as West Belfast MP". BBC. 20 January 2011. Archived from the original on 23 January 2011. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ "Louth – RTÉ News". Raidió Teilifís Éireann. 28 February 2011. Archived from the original on 28 February 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ^ "Gerry Adams". Big Think. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ "Gerry Adams picked for guard of honour for Mandela". The Journal. 14 December 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "Madiba's legacy of hope – Gerry Adams on being at the funeral of Nelson Mandela". An Phoblacht. 19 December 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "Prince Charles and Gerry Adams share historic handshake". The Guardian. Henry McDonald. 19 May 2015 Archived 21 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ "Sinn Fein's Adams to outline succession plan in November". Reuters.com. 5 September 2017. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ^ McDonald, Henry (5 September 2017). "Gerry Adams signals intention to stand down as Sinn Féin leader". TheGuardian.com. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ^ Downing, John (5 September 2017). "Gerry Adams will seek re-election as Sinn Féin leader and then set out plans to step down". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ^ McDonald succeeds Adams as President of Sinn Féin Archived 10 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine. RTÉ. Published 11 February 2018. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ^ "Gerry Adams demands bombers who attacked his house explain why". The Independent. Archived from the original on 14 July 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ Ainsworth, Paul (16 July 2018). "Video: CCTV captures attack on Gerry Adams' home". The Irish News. Archived from the original on 16 July 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ^ McKittrick, David (10 April 2006). "Gerry Adams: 'The war is over for me ... but is it over for Ian Paisley?'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 30 June 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Moloney 2002, p. 129.

- ^ Adams declares Antrim interest Archived 8 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine HoganStand, 5 September 2012.

- ^ "Liam Adams convicted of raping and abusing daughter". BBC News. 1 October 2013. Archived from the original on 1 October 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ^ McDonald, Henry (1 October 2013). "Liam Adams found guilty of raping his eldest daughter". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 October 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ^ "Sinn Féin's Gerry Adams reveals family abuse history". The BBC. 20 December 2009. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2009.

- ^ Adams reveals family history of abuse Archived 24 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. RTÉ News and Current Affairs. Sunday, 20 December 2009. Audio interview also available from that page.

- ^ Liam Adams jailed for raping and abusing daughter Archived 24 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, 27 November 2013.

- ^ "Liam Adams: 'No missed or delayed diagnosis' in sex offender's death". BBC News. 6 October 2021.

- ^ "Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams apologises for racial slur". www.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ "Adams admits N-word tweet 'was inappropriate'". RTÉ.ie. 2 May 2016. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ "Adams Apologises For Using 'N-Word' In Tweet". Sky News. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ "Gerry Adams, Sinn Fein president, tweets N-word". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on 4 May 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ Bailey, Issac (2 May 2016). "Facing the consequences of using the N-word". CNN. Archived from the original on 11 May 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ McDonald, Henry (2 May 2016). "Gerry Adams defends N-word tweet". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ Brennan, Cianan (4 May 2016). ""The Irish were sold as slaves" – Gerry Adams has spoken once again about THAT tweet". TheJournal.ie. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ^ Linehan, Hugh (11 May 2016). "Sinn Féin not allowing facts derail good 'Irish slaves' yarn". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ^ Downing, John; Treacy, Ciara; McAdam, Noel (3 May 2016). "Adams hit with furious backlash after racial slur – Independent.ie". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ^ Grant, Martin (9 May 2016). "Gerry Adams reignites N-word row with civil rights blog comparison – BelfastTelegraph.co.uk". Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ^ "It's all eyes on the 73rd Venice Film Festival". Breaking News. 29 July 2016. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ "Pierce Brosnan channels Gerry Adams in new IRA thriller The Foreigner". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

Works cited

[edit]- McDonald, Henry; Cusack, Jim (2004). UDA: Inside the Heart of Loyalist Terror. Penguin Ireland. ISBN 978-1-84488-020-1.

- Moloney, Ed (2002). A Secret History of the IRA. Penguin Books. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-14-101041-0.

- Sharrock, David; Devenport, Mark (1997). Man of War, Man of Peace The Unauthorised Biography of Gerry Adams. London: Macmillan. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-330-35396-0.

- Taylor, Peter (1997). Provos The IRA & Sinn Féin. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-7475-3818-9.

Further reading

[edit]- de Bréadún, Deaglán (22 January 2018). "Gerry Adams – the face of Irish republicanism – hands over at Sinn Féin". WikiTribune.

- Keena, Colm (1990). Biography of Gerry Adams. Cork: Mercier Press.

- Keefe, Patrick Radden (2019). Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland. Doubleday New York.

- Randolph, Jody Allen (2010). "Gerry Adams, August 2009". Close to the Next Moment: Interviews from a Changing Ireland. Manchester: Carcanet. ISBN 9781847770486.

External links

[edit]- Gerry Adams on Twitter

- Léargas blog by Gerry Adams

- Column archive at The Guardian

- Gerry Adams Archived 23 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine Sinn Féin profile

- Record in Parliament at TheyWorkForYou

- Gerry Adams at IMDb

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Gerry Adams collected news and commentary at The Guardian

- Gerry Adams collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- Gerry Adams Man Of War and Man Of Peace? Anthony McIntyre, The Blanket, 28 April 2004

- Interview with Gerry Adams February 2006

- Gerry Adams Profile at New Statesman

- 1948 births

- 21st-century writers from Northern Ireland

- Irish nationalists

- Irish republicans

- Irish republicans interned without trial

- Leaders of Sinn Féin

- Living people

- Male non-fiction writers from Northern Ireland

- Members of the 31st Dáil

- Members of the 32nd Dáil

- Members of the Northern Ireland Forum

- Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for Belfast constituencies (since 1922)

- Northern Ireland MPAs 1982–1986

- Northern Ireland MLAs 1998–2003

- Northern Ireland MLAs 2003–2007

- Northern Ireland MLAs 2007–2011

- People educated at St. Mary's Christian Brothers' Grammar School, Belfast

- Politicians from Belfast

- Shooting survivors

- Socialists from Northern Ireland

- Sinn Féin MLAs

- Sinn Féin MPs (post-1921)

- Sinn Féin TDs (post-1923)

- UK MPs 1983–1987

- UK MPs 1987–1992

- UK MPs 1997–2001

- UK MPs 2001–2005

- UK MPs 2005–2010

- UK MPs 2010–2015

- Writers from Belfast

- Victims of bomb threats