Victory ship

SS Red Oak Victory, now a museum ship

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | Victory ship |

| Builders | 6 shipyards in the US |

| Cost | US$2,522,800 (1943)[1] per unit |

| Planned | 615 |

| Completed | 534 |

| Cancelled | 81 |

| Preserved | 3 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Cargo ship |

| Tonnage | |

| Displacement | 15,200 tons (at 28-foot draft)[2][clarification needed] |

| Length | 455 ft (138.7 m)[2] |

| Beam | 62 ft (18.9 m)[2] |

| Draft | 28 ft (8.5 m)[2] |

| Depth of hold | 38 ft (11.6 m)[2] |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 15–17 knots (28–31 km/h; 17–20 mph) |

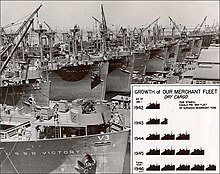

The Victory ship was a class of cargo ship produced in large numbers by American shipyards during World War II to replace losses caused by German submarines. They were a more modern design compared to the earlier Liberty ship, were slightly larger and had more powerful steam turbine engines, giving higher speed to allow participation in high-speed convoys and make them more difficult targets for German U-boats. A total of 531 Victory ships were built in between 1944 and 1946.[3][4]

VC2 design

[edit]

One of the first acts of the United States War Shipping Administration upon its formation in February 1942 was to commission the design of what came to be known as the Victory class. Initially designated EC2-S-AP1, where EC2 = Emergency Cargo, type 2 (Load Waterline Length between 400 and 450 feet (120 and 140 m)), S = steam propulsion with AP1 = one aft propeller (EC2-S-C1 had been the designation of the Liberty ship design), it was changed to VC2-S-AP1 before the name "Victory Ship" was officially adopted on 28 April 1943. The ships were built under the Emergency Shipbuilding program.[2]

The design was an enhancement of the Liberty ship, which had been successfully produced in extraordinary numbers. Victory ships were slightly larger than Liberty ships, 14 feet (4.3 m) longer at 455 feet (139 m), 6 feet (1.8 m) wider at 62 ft (19 m), and drawing one foot more at 28 feet (8.5 m) loaded.[2] Displacement was up just under 1,000 tons, to 15,200. With a raised forecastle and a more sophisticated hull shape to help achieve the higher speed, they had a quite different appearance from Liberty ships.

To make them less vulnerable to U-boat attacks, Victory ships made 15 to 17 knots (28 to 31 km/h), 4 to 6 knots (7.4 to 11.1 km/h) faster than the Libertys, and had longer range. The extra speed was achieved through more modern, efficient engines. Rather than the Libertys' 2,500 horsepower (1,900 kW) triple expansion steam engines, Victory ships were designed to use either Lentz type reciprocating steam engines (one ship only, oil fired), Diesel engines (one ship) or steam turbines (the rest, all oil fired) (variously putting out between 6,000 and 8,500 hp (4,500 and 6,300 kW)). Another improvement was electrically powered auxiliary equipment, rather than steam-driven machinery.

To prevent the hull cracks that many Liberty ships developed—making some break in half—the spacing between frames was widened from 30 inches (760 mm) to 36 inches (910 mm), making the ships less stiff and more able to flex. Like Liberty ships, the hull was welded rather than riveted.[5]

The VC2-S-AP2, VC2-S-AP3, and VC2-M-AP4 were armed with a 5-inch (127 mm)/38 caliber stern gun for use against submarines and surface ships, and a bow-mounted 3-inch (76 mm)/50 caliber gun and eight 20 mm cannon for use against aircraft. These were manned by United States Navy Armed Guard personnel. The VC2-S-AP5 Haskell-class attack transports were armed with the 5-inch stern gun, one quad 40 mm Bofors cannon, four dual 40 mm Bofors cannon, and ten single 20 mm cannon. The Haskells were operated and crewed exclusively by U.S. Navy personnel.

The Victory ship was noted for good proportion of cubic between holds for a cargo ship of its day. A Victory ship's cargo hold one, two and five hatches are single rigged with a capacity of 70,400, 76,700, and 69,500 bale cubic feet respectively. Victory ships hold three and four hatches are double rigged with a capacity of 136,100 and 100,300 bale cubic feet respectively.[6] Victory ships have built-in mast, booms and derrick cranes and can load and unload their own cargo without dock side cranes or gantry if needed.[7]

Construction

[edit]The first vessel was SS United Victory launched at Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation on 12 January 1944 and completed on 28 February 1944, making her maiden voyage a month later. American vessels frequently had a name incorporating the word "Victory".[8] After United Victory, the next 34 vessels were named after allied countries, the following 218 after American cities, the next 150 after educational institutions and the remainder given miscellaneous names. The AP5 type attack transports were named after United States counties, without "Victory" in their name, with the exception of USS Marvin H. McIntyre, which was named after President Roosevelt's late personal secretary.

Although initial deliveries were slow—only 15 had been delivered by May 1944—by the end of the war 531 had been constructed. The Commission cancelled orders for a further 132 vessels, although three were completed in 1946 for the Alcoa Steamship Company, making a total built in the United States of 534, made up of:

| Quantity Built |

Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 272 | VC2-S-AP2 | 6,000 hp (4.5 MW) general cargo vessels |

| 141 | VC2-S-AP3 | 8,500 hp (6.3 MW) vessels |

| 1 | VC2-M-AP4 | Diesel |

| 117 | VC2-S-AP5 | Haskell-class attack transports |

| 3 | VC2-S-AP7 | Post war completion |

Of the wartime construction, 414 were of the standard cargo variant and 117 were attack transports.[2] Because the Atlantic battle had been won by the time the first of the Victory ships appeared none were sunk by U-boats. Three were sunk by Japanese kamikaze attack in April 1945.

Many Victory ships were converted to troopships to bring US soldiers home at the end of World War II as part of Operation Magic Carpet. A total of 97 Victory ships were converted to carry up to 1,600 soldiers. To convert the ships the cargo hold were converted to bunk beds and hammocks stacked three high for hot bunking. Mess halls and exercise places were also added.[9] Some examples of Victory troopship are: SS Aiken Victory, SS Chanute Victory, SS Cody Victory, SS Colby Victory, SS Cranston Victory, SS Gustavus Victory, SS Hagerstown Victory, SS Maritime Victory, and SS U.S.S.R. Victory.[10][11][12][13][14]

Some 184 Victory ships served in the Korean War and a 100 Victory ships served in the Vietnam War.[15][16] Many were sold and became commercial cargo ships and a few commercial passenger ships. Some were laid up in the United States Navy reserve fleets and then scrapped or reused. Many saw postwar conversion and various uses for years afterward. The single VC2-M-AP4 Diesel-powered MV Emory Victory operated in Alaskan waters for the Bureau of Indian Affairs as North Star III.[2] AP3 types South Bend Victory and Tuskegee Victory were converted in 1957–58 to ocean hydrographic surveying ships USNS Bowditch and Dutton, respectively.[2] Dutton aided in locating the lost hydrogen bomb following the 1966 Palomares B-52 crash.[17]

Starting in 1959, several were removed from the reserve fleet and refitted for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. One such ship was SS Kingsport Victory, which was renamed USNS Kingsport and converted into the world's first satellite communications ship. Another was the former Haiti Victory, which recovered the first man-made object to return from orbit, the nose cone of Discoverer 13, on 11 August 1960. USS Sherburne was converted in 1969–1970 to the range instrumentation ship USNS Range Sentinel for downrange tracking of ballistic missile tests.[2]

Four Victory ships became fleet ballistic missile cargo ships transporting torpedoes, Poseidon missiles, packaged petroleum, and spare parts to deployed submarine tenders:[2]

- USNS Norwalk, built as SS Norwalk Victory

- USNS Furman, built as SS Furman Victory

- USNS Victoria, built as SS Ethiopia Victory

- USNS Marshfield, built as SS Marshfield Victory

In the 1960s two Victory ships were reactivated and converted to technical research ships by the U.S. Navy with the hull type AGTR. SS Iran Victory became USS Belmont and SS Simmons Victory became USS Liberty. Liberty was attacked and severely damaged by Israeli forces in June 1967 and subsequently decommissioned and struck from the Naval Register. Belmont was decommissioned and stricken in 1970. Baton Rouge Victory was sunk in the Mekong delta by a Viet Cong mine in August 1966 and temporarily blocked the channel to Saigon.[2]

Cost

[edit]According to the War Production Board minutes in 1943, the Victory Ship had a relative cost of $238 per deadweight ton (10,500 deadweight tonnage) [1] for $2,522,800, equivalent to $35,500,000 in 2023.

Shipyards

[edit]Most Victory ships were constructed in six West Coast and one Baltimore emergency shipyards that were set up in World War II to build Liberty, Victory, and other ships. The Victory ship was designed to be able to be assembled by the smallest capacity crane at these shipyards.[2]

| Shipyard | Location | Quantity Yard |

Type | Quantity Type |

MCV Hull Numbers | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bethlehem Fairfield | Baltimore, Maryland | 94 | VC2-S-AP2 | 93 | 602–653, 816–856 | 23 more cancelled |

| VC2-M-AP4 | 1 | 654 | Diesel engine variant | |||

| California Shipbuilding | Wilmington, California | 131 | VC2-S-AP3 | 32 | 1–24, 27, 29, 31–33, 37, 41, 42 | |

| VC2-S-AP5 | 30 | 25, 26, 28, 30, 34–36, 38–40, 43–62 | 63–66 Transferred to Vancouver as 812–815 | |||

| VC2-S-AP2 | 69 | 67–84, 767–811, 885–890 | 10 more cancelled | |||

| Kaiser Shipbuilding | Vancouver, Washington | 31 | VC2-S-AP5 | 31 | 655–681, 812–815 | 17 more cancelled |

| Oregon Shipbuilding | Portland, Oregon | 136 | VC2-S-AP3 | 99 | 85–116, 147–189, 682–701, 872–875 | 19 more cancelled |

| VC2-S-AP5 | 34 | 117–146, 860–863 | 12 more cancelled | |||

| VC2-S-AP7 | 1 | 866 | Originally AP5 | |||

| VC2-S1-AP7 | 2 | 876, 877 | Originally AP3 | |||

| Kaiser Richmond No. 1 Yard | Richmond, California | 53 | VC2-S-AP3 | 10 | 525–534 | |

| VC2-S-AP2 | 43 | 535–550, 581–596, 702–711 | ||||

| Kaiser Richmond No. 2 Yard | 89 | VC2-S-AP5 | 22 | 552–573 | ||

| VC2-S-AP2 | 67 | 574–580, 597–601, 712–766 |

Ships in class

[edit]

- United States Merchant Marine, 414 SS Victory cargo ships. World War II, some used in the Korean War and Vietnam War.

- 97 Victory ships temporarily converted to World War II troopship.[20]

- One ship SS Pratt Victory with engineering spaces converted to unmanned operation and used with a reduced Navy crew as a temporary minesweeper in 1945 and 1946.[21][22]

- Seagoing cowboys ships, 1946 to 1947 temporary conversion of 46 Merchant Marine Victory ships to transport relief livestock.

- US Navy conversions

- Haskell-class attack transports (APA), 117 built.

- Boulder Victory-class cargo ships (AK), 20 built.

- Greenville Victory-class cargo ships (AK), 9 Victory ships under US Navy ownership for Korean War.

- Lt. James E. Robinson-class aircraft transports (AKV), 1950 conversion of two ships: USNS Lt. James E. Robinson and USNS Sgt. Jack J. Pendleton

- Denebola-class stores ships (AF), 3 Victory ships that came under US Navy ownership in 1952: USS Denebola, USS Regulus and USNS Perseus. A fourth ship, USNS Asterion, would be converted to this class in 1961.

- Bowditch-class survey ships (AGS), 1957 conversion of 3 ships: Bowditch, Dutton, Michelson.

- Phoenix-class auxiliary ships (AG), 1960 3 US Navy Forward Floating Depots: Phoenix, Provo and Cheyenne

- Watertown-class missile range instrumentation ships (T-AGM), 1960 conversion of 3 ships: Watertown, Huntsville and Wheeling

- Longview-class missile range instrumentation ships (T-AGM), 1960 conversion of 3 ships: Longview, Private Joe E. Mann and Dalton Victory

- Kingsport telemetry ship (AG), 1961 conversion of one ship, USNS Kingsport.

- Belmont-class technical research ships (AGTR), 1963 conversion of 2 ships for Sigint: USS Belmont and USS Liberty

- Norwalk class ballistic missile submarine support cargo ships (AK), four converted in 1963: T-AK-279, T-AK-280, T-AK-281, T-AK-282

- Range Sentinel telemetry ship (AGM), 1971 conversion of one ship: USS Sherburne

Survivors

[edit]

Three are preserved as museum ships:

- SS American Victory (Tampa, Florida)

- SS Lane Victory (Los Angeles, California)

- SS Red Oak Victory (Richmond, California)

See also

[edit]- Empire ships

- Liberty ship

- List of Victory ships

- Port Chicago disaster

- T2 tanker

- Type C1 ship

- Type C2 ship

- Type C3 ship

- U.S. Merchant Marine Academy

- Murmansk Run

- World War II United States Merchant Navy

- Away All Boats about Victory Attack transport

- USMS North Star III

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Civilian Production Administration Bureau of Demobilization (1946). Minutes of the War Production Board January 20, 1942 - October 9, 1945. Historical Reports on War Administration: War Production Board. Documentary Publication. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 234.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Culver, John A., CAPT USNR "A time for Victories" United States Naval Institute Proceedings February 1977 pp. 50–56

- ^ Jaffee, Capt. Walter W., The Lane Victory: The Last Victory Ship in War and in Peace, 2nd ed., p. 14, The Glencannon Press, Palo Alto, CA, 1997.

- ^ MARAD, Victory Ship, U.S. Maritime Commission design type VC2-S-AP2

- ^ "Victory Ship Design". GlobalSecurity.org. 22 July 2011. Archived from the original on 16 November 2012.

- ^ "An Analysis of General Cargo Handing Problems, Developments, and Proffered Solutions, BY L. H. QUACKENBUSH, ASSOCIATE". Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- ^ "Cargo hold tour, SS Lane". Archived from the original on 2 August 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- ^ This can be compared with British and Canadian practices, which respectively often used "Fort" and "Park" for their own ships.

- ^ Chapter 2 After ASTP, Across the Atlantic to England Under Siege, By Lester Segarnick

- ^ "ww2troopships.com crossings in 1945". Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^ "Troop Ship of World War II, April 1947, pp. 356–357" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^ "69th infantry division, newsletter, 1986" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^ The Nebraska State Journal from Lincoln, Nebraska, 26 December 1945, p. 4

- ^ Binghamton NY Press Grayscale 1945 – Fulton History, Oct. 15, 1945

- ^ "usmm.org Korean War ships". Archived from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ "usmm.org Vietnam War ships". Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ Melson, Lewis B., CAPT USN "Contact 261" United States Naval Institute Proceedings June 1967

- ^ "WWII Construction Records – Private-Sector Shipyards that Built Ships for the U.S. Maritime Commission". Archived from the original on 23 October 2006. Retrieved 3 November 2006.

- ^ "Victory Ships built by the United States Maritime Commission during World War II – Listed by Shipyard". Archived from the original on 25 October 2006. Retrieved 4 November 2006.

- ^ usmm.org Troopships

- ^ Looking for trouble, the Guinea Pig Squadron

- ^ Pratt Victory photo, mine Hunter

References

[edit]- SS American Victory Web site

- SS Lane Victory Web site

- U-Boat net

- United States National Park Service document on historical significance of SS Red Oak Victory

- Lane, Frederic, Ships for Victory: A History of Shipbuilding under the U.S. Maritime Commission in World War II. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8018-6752-5

- Sawyer L. A., and W. H. Mitchell, Victory Ships and Tankers; the history of the "Victory" type cargo ships and of the tankers built in the United States of America during World War II. Cambridge, Maryland: Cornell Maritime Press, 1974

- Heal, S. C., A Great Fleet of Ships: The Canadian Forts and Parks. Vanwell, 1993 ISBN 978-1551250236

- All About Victory Ships at TAGS Ship Web Site

External links

[edit]- Liberty Ships and Victory Ships, America's Lifeline in War Archived 11 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine – a lesson on Liberty ships and Victory ships from the National Park Service's Teaching with Historic Places

- "Victory Ship Makes 15 knots, Outstrips Liberty" Popular Mechanics, December 1943