Operation Reinhard

| Operation Reinhard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | General Government in German-occupied Poland |

| Date | March 1942 – November 1943[2] |

| Incident type | Mass deportations to extermination camps |

| Perpetrators | Odilo Globočnik, Hermann Höfle, Richard Thomalla, Erwin Lambert, Christian Wirth, Heinrich Himmler, Franz Stangl and others. |

| Organizations | SS, Order Police battalions, Sicherheitsdienst, Trawnikis |

| Camp | Belzec Sobibor Treblinka Additional: Majdanek Auschwitz II |

| Ghetto | European and Jewish ghettos in German-occupied Poland including Białystok, Częstochowa, Kraków, Lublin, Łódź, Warsaw and others |

| Victims | Around 2 million Jews |

Operation Reinhard or Operation Reinhardt (German: Aktion Reinhard or Aktion Reinhardt; also Einsatz Reinhard or Einsatz Reinhardt) was the codename of the secret German plan in World War II to exterminate Polish Jews in the General Government district of German-occupied Poland. This deadliest phase of the Holocaust was marked by the introduction of extermination camps.[3] The operation proceeded from March 1942 to November 1943; about 1.47 million or more Jews were murdered in just 100 days from late July to early November 1942, a rate which is approximately 83% higher than the commonly suggested figure for the kill rate in the Rwandan genocide.[2] In the time frame of July to October 1942, the overall death toll, including all killings of Jews and not just Operation Reinhard, amounted to two million killed in those four months alone.[4] It was the single fastest rate of genocidal killing in history.[5]

During the operation, as many as two million Jews were sent to Bełżec, Sobibór, and Treblinka to be murdered in purpose-built gas chambers.[3][6] In addition, facilities for mass-murder using Zyklon B were developed at about the same time at the Majdanek concentration camp[3] and at Auschwitz II-Birkenau, near the earlier-established Auschwitz I camp.[7]

Background

After the German–Soviet war began, the Nazis undertook their European-wide "Final Solution to the Jewish Question". In January 1942, during a secret meeting of German leaders chaired by Reinhard Heydrich, Operation Reinhard was drafted; it was soon to become a significant step in the systematic murder of the Jews in occupied Europe, beginning in the General Government district of German-occupied Poland. Within months, three top-secret camps (at Bełżec, Sobibór, and Treblinka) were built to efficiently murder tens of thousands of Jews every day.

These camps differed from Auschwitz and Majdanek, which initially operated as forced-labour camps before facilities for mass death were installed (gas chambers, crematoria etc.) Even after becoming death camps fitted with crematoria, konzentrationslager like Auschwitz remained largely dedicated to forced labor.[8] Unlike "mixed" extermination camps, the extermination camps of Operation Reinhard kept no prisoners, except as needed to advance the camp's industrial-scale murder. Very few Jews escaped death (notably, only two at Bełżec).[9] All other victims were murdered on arrival.[10]

The organizational apparatus behind the new extermination plan had been put to the test already during the "euthanasia" Aktion T4 programme ending in August 1941, during which more than 70,000 Polish and German disabled men, women, and children were murdered.[11] The SS officers responsible for the Aktion T4, including Christian Wirth, Franz Stangl, and Irmfried Eberl, were all given key roles in the implementation of the "Final Solution" in 1942.[12]

Operational name

The origin of the operation's name is debated by Holocaust researchers. Various German documents spell the name differently, some with "t" after "d" (as in "Aktion Reinhardt"), others without it. Yet another spelling (Einsatz Reinhart) was used in the Höfle Telegram.[13] It is generally believed that Aktion Reinhardt, outlined at the Wannsee Conference on 20 January 1942, was named after Reinhard Heydrich, the coordinator of the so-called Final Solution of the Jewish Question, which entailed the extermination of the Jews living in the European countries occupied by Nazi Germany. Heydrich was attacked by British-trained Czechoslovakian agents on 27 May 1942 and died of his injuries eight days later.[14] The earliest memo spelling out Einsatz Reinhard was relayed two months later.[13]

Death camps

On 13 October 1941, SS and Police Leader Odilo Globočnik headquartered in Lublin received an oral order from Himmler – anticipating the fall of Moscow – to begin the construction of the first extermination camp at Bełżec in the General Government territory of occupied Poland. The order preceded the Wannsee Conference by three months.[15] The new camp was operational from 17 March 1942, with leadership brought in from Germany under the guise of Organisation Todt (OT).[15]

Globočnik was given control over the entire programme. All the secret orders he received came directly from Himmler and not from SS-Gruppenführer Richard Glücks, head of the greater Nazi concentration camp system, which was run by the SS-Totenkopfverbände and engaged in slave labour for the war effort.[16] Each death camp was managed by between 20 and 35 officers from the Totenkopfverbände (Death's Head Units) sworn to absolute secrecy,[17] and augmented by the Aktion T4 personnel selected by Globočnik. The extermination program was designed by them based on prior experience from the forced euthanasia centres. The bulk of the actual labour at each "final solution" camp was performed by up to 100 mostly Ukrainian Trawniki guards, recruited by SS-Hauptsturmführer Karl Streibel from among the Soviet prisoners of war,[18] and by up to a thousand Sonderkommando prisoners whom the Trawniki guards used to terrorise.[19][20] The SS called their volunteer guards "Hiwis", an abbreviation of Hilfswillige (lit. "willing to help"). According to the testimony of SS-Oberführer Arpad Wigand during his 1981 war crimes trial in Hamburg, only 25 percent of recruited collaborators could speak German.[18]

By mid-1942, two more death camps had been built on Polish lands: Sobibór (operational by May 1942) under the leadership of SS-Hauptsturmführer Franz Stangl, and Treblinka (operational by July 1942) under SS-Obersturmführer Irmfried Eberl.[21]

The SS pumped exhaust fumes from a large internal-combustion engines through long pipes into sealed rooms, murdering the people inside by carbon monoxide poisoning. Beginning in February–March 1943, the bodies of the dead were exhumed and cremated in pits. Treblinka, the last camp to become operational, used knowledge learned by the SS previously. With two powerful engines,[a] run by SS-Scharführer Erich Fuchs,[21] and the gas chambers soon rebuilt of bricks and mortar, this death factory had murdered between 800,000 and 1,200,000 people within 15 months, disposed of their bodies, and sorted their belongings for shipment to Germany.[29][30]

The techniques used to deceive victims and the camps' overall layout were based on a pilot project of mobile killing conducted at the Chełmno extermination camp (Kulmhof), which entered operation in late 1941 and used gas vans. Chełmno was not a part of Reinhard.[31] It came under the direct control of SS-Standartenführer Ernst Damzog, commander of the SD in Reichsgau Wartheland. It was set up around a manor house similar to Sonnenstein. The use of gas vans had been previously tried and tested in the mass murder of Polish prisoners at Soldau,[32] and in the extermination of Jews on the Russian Front by the Einsatzgruppen. Between early December 1941 and mid-April 1943,[33] 160,000 Jews were sent to Chełmno from the General Government via the Ghetto in Łódź.[34] Chełmno did not have crematoria; only the mass graves in the woods. It was a testing ground for the establishment of faster methods of murdering and incinerating people, marked by the construction of stationary facilities for the mass murder a few months later. The Reinhard death camps adapted progressively as each new site was built.[35]

Taken as a whole, Globočnik's camps at Bełżec, Sobibór, and Treblinka had almost identical design, including staff members transferring between locations. The camps were situated within wooded areas well away from population centres. All were constructed near branch lines that linked to the Ostbahn.[36] Each camp had an unloading ramp at a fake railway station, as well as a reception area that contained undressing barracks, barber shops, and money depositories. Beyond the receiving zone, at each camp was a narrow, camouflaged path known as the Road to Heaven (called Himmelfahrtsstraße or der Schlauch by the SS),[37] which led to the extermination zone consisting of gas chambers, and the burial pits, up to 10 metres (33 ft) deep, later replaced by cremation pyres with rails laid across the pits on concrete blocks; refuelled continuously by the Totenjuden. Both Treblinka and Bełżec were equipped with powerful crawler excavators from Polish construction sites in the vicinity, capable of most digging tasks without disrupting surfaces.[38][39] At each camp, the SS guards and Ukrainian Trawnikis lived in a separate area from the Jewish work units. Wooden watchtowers and barbed-wire fences camouflaged with pine branches surrounded all camps.[40]

The killing centres had no electric fences, as the size of the prisoner Sonderkommandos (work units) remained comparatively easy to control – unlike in camps such as Dachau and Auschwitz. To assist with the arriving transports only specialised squads were kept alive, removing and disposing of bodies, and sorting property and valuables from the dead victims. The Totenjuden forced to work inside death zones were deliberately isolated from those who worked in the reception and sorting area. Periodically, those who worked in the death zones would be killed and replaced with new arrivals to remove any potential witnesses to the scale of the mass murder.[41]

During Operation Reinhard, Globočnik oversaw the systematic murder of more than 2,000,000 Jews from Poland, Czechoslovakia, France, the Reich (Germany and Austria), the Netherlands, Greece, Hungary, Italy and the Soviet Union. An undetermined number of Roma were also murdered in these death camps, many of them children.[42]

Extermination process

To achieve their intended purpose, all death camps used subterfuge and misdirection to conceal the truth and trick their victims into cooperation. This element had been developed in Aktion T4, when disabled and handicapped people were taken away for "special treatment" by the SS from "Gekrat" wearing white laboratory coats, thus giving the process an air of medical authenticity. After supposedly being assessed, the unsuspecting T4 patients were transported to killing centres. The same euphemism "special treatment" (Sonderbehandlung) was used in the Holocaust.[43]

The SS used a variety of ruses to move thousands of new arrivals travelling in Holocaust trains to the disguised killing sites without panic. Mass deportations were called "resettlement actions"; they were organised by special Commissioners and conducted by uniformed police battalions from Orpo and Schupo in an atmosphere of terror.[44][45] Usually, the deception was absolute; in August 1942, people of the Warsaw Ghetto lined up for several days to be "deported" to obtain bread allocated for travel.[46] Jews unable to move or attempting to flee were shot on the spot.[47] Even though death in the cattle cars from suffocation and thirst was rampant, affecting up to 20 percent of trainloads, most victims were willing to believe that the German intentions were different.[48] Once alighted, the prisoners were ordered to leave their luggage behind and march directly to the "cleaning area" where they were asked to hand over their valuables for "safekeeping". Common tricks included the presence of a railway station with awaiting "medical personnel" and signs directing people to disinfection facilities. Treblinka also had a booking office with boards naming the connections for other camps further east.[49]

The Jews most apprehensive of danger were brutally beaten to speed up the process.[50] At times, the new arrivals who had suitable skills were selected to join the Sonderkommando. Once in the changing area, the men and boys were separated from the women and children and everyone was ordered to disrobe for a communal bath: "quickly – they were told – or the water will get cold".[51] The old and sick, or slow, prisoners were taken to a fake infirmary named the Lazarett, that had a large mass grave behind it. They were killed by a bullet in the neck, while the rest were being forced into the gas chambers.[52][53][54]

To drive the naked people into the execution barracks housing the gas chambers, the guards used whips, clubs, and rifle butts. Panic was instrumental in filling the gas chambers because the need to evade blows on their naked bodies forced the victims rapidly forward. Once packed tightly inside (to minimize available air), the steel air-tight doors with portholes were closed. The doors, according to Treblinka Museum research, originated from the Soviet military bunkers around Białystok.[55] Although other methods of extermination, such as the cyanic poison Zyklon B, were already in use at other Nazi killing centres such as Auschwitz, the Aktion Reinhard camps used lethal exhaust gases from captured Soviet tank engines.[56] Fumes would be discharged directly into the gas chambers for a given period, then the engines would be switched off. SS guards would determine when to reopen the gas doors based on how long it took for the screaming to stop from within (usually 25 to 30 minutes). Special teams of camp inmates (Sonderkommando) would then remove the corpses on flatbed carts. Before the corpses were thrown into grave pits, gold teeth were removed from mouths, and orifices were searched for jewellery, currency, and other valuables. All acquired goods were managed by the SS-Wirtschafts-Verwaltungshauptamt (Main SS Economic and Administrative Department).

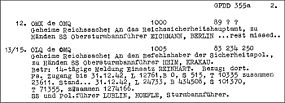

During the early phases of Operation Reinhard, bodies were simply thrown into mass graves and covered with lime. From 1943, to hide the evidence of the crime, the victims' remains were burned in open air pits. Special Leichenkommando (corpse units) had to exhume bodies from the mass graves around these death camps for incineration. Reinhard still left a paper trail; in January 1943, Bletchley Park intercepted an SS telegram by SS-Sturmbannführer Hermann Höfle, Globočnik's deputy in Lublin, to SS-Obersturmbannführer Adolf Eichmann in Berlin. The decoded Enigma message contained statistics showing a total of 1,274,166 arrivals at the four Aktion Reinhard camps until the end of 1942 but the British code-breakers did not understand the meaning of the message, which amounted to material evidence of how many people the Germans had murdered.[57][58]

Camp commandants

| Extermination camp | Commandant | Period | Estimated deaths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bełżec | SS-Sturmbannführer Christian Wirth | December 1941 – 31 July 1942 | 600,000[59] |

| SS-Hauptsturmführer Gottlieb Hering | 1 August 1942 – December 1942 | ||

| Sobibór | SS-Hauptsturmführer Richard Thomalla | March 1942 – April 1942 Camp construction | |

| SS-Hauptsturmführer Franz Stangl | May 1942 – September 1942 | 250,000 [60] | |

| SS-Hauptsturmführer Franz Reichleitner | September 1942 – October 1943 | ||

| Treblinka | SS-Hauptsturmführer Richard Thomalla | May 1942 – June 1942 Camp construction | |

| SS-Obersturmführer Irmfried Eberl | July 1942 – September 1942 | 800,000–900,000 [61] | |

| SS-Hauptsturmführer Franz Stangl | September 1942 – August 1943 | ||

| SS-Untersturmführer Kurt Franz | August 1943 – November 1943 | ||

| Lublin/Majdanek[62] | SS-Standartenführer Karl-Otto Koch | October 1941 – August 1942 | 130,000 [63] (78,000 confirmed) [64] |

| SS-Sturmbannführer Max Koegel | August 1942 – November 1942 | ||

| SS-Obersturmführer Hermann Florstedt | November 1942 – October 1943 | ||

| SS-Obersturmbannführer Martin Gottfried Weiss | November 1, 1943 – May 5, 1944 | ||

| SS-Obersturmbannführer Arthur Liebehenschel | May 5, 1944 – July 22, 1944 | ||

Temporary substitution policy

In the winter of 1941, before the Wannsee Conference but after the commencement of Operation Barbarossa, the Nazis' need for forced labor greatly intensified. Himmler and Heydrich approved a Jewish substitution policy in Upper Silesia and in Galicia under the "extermination through labour" doctrine.[65] Many Poles had already been sent to the Reich, creating a labour shortage in the General Government.[66] Around March 1942, while the first extermination camp (Bełżec) began gassing, the deportation trains arriving in the Lublin reservation from Germany and Slovakia were searched for the Jewish skilled workers. After selection, they were delivered to Majdan Tatarski instead of for "special treatment" at Bełżec. For a short time, these Jewish laborers were temporarily spared death, while their families and all others were murdered.[66] Some were relegated to work at a nearby airplane factory or as forced labor in the SS-controlled Strafkompanies and other work camps. Hermann Höfle was one of the chief supporters and implementers of this policy.[16] There were problems with food supplies and the ensuing logistical challenges. Globočnik and Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger complained and the mass transfer was stopped even before the three extermination camps were operational.[66]

Disposition of the property of the victims

Approximately 178 million German Reichsmarks' worth of Jewish property (equivalent to 727 million 2021 euros) was taken from the victims, with vast transfers of gold and valuables to the Reichsbank's "Melmer" account, Gold Pool, and monetary reserve.[67] Not only the German authorities were in receipt of Jewish property, because corruption was rife within the death camps. Many of the individual SS members and policemen involved in the murders took cash, property, and valuables for themselves. The higher-ranking SS men stole on an enormous scale. It was a common practice among the top echelon.[citation needed] Two Majdanek commandants, Karl-Otto Koch and Hermann Florstedt, were tried by the SS for it in April 1945.[68] SS-Sturmbannführer Georg Konrad Morgen, an SS judge from the SS Courts Office, prosecuted so many Nazi officers for individual violations that Himmler personally ordered him to restrain his cases by April 1944.[69][70]

Aftermath and cover up

Operation Reinhard ended in November 1943. Most of the staff and guards were then sent to northern Italy for further Aktion against Jews and local partisans. Globočnik went to the San Sabba concentration camp, where he supervised the detention, torture and murder of political prisoners. To cover up the mass murder of more than two million people in Poland during Operation Reinhard, the Nazis implemented the secret Sonderaktion 1005, also called Aktion 1005 or Enterdungsaktion ("exhumation action"). The operation, which began in 1942 and continued until the end of 1943, was designed to remove all traces that mass murder. Leichenkommando ("corpse units") comprising camp prisoners were created to exhume mass graves and cremate the buried bodies, using giant grills made from wood and railway tracks. Afterwards, bone fragments were ground up in special milling machines, and all remains were then re-buried in new pits. The Aktion was overseen by squads of Trawniki guards.[71][72] After the war, some of the SS officers and guards were tried and sentenced at the Nuremberg trials for their role in Operation Reinhard and Sonderaktion 1005. Many others escaped conviction, such as Ernst Lerch, Globočnik's deputy and chief of his Main Office, whose case was dropped for lack of witness testimony.[73]

See also

- Action 14f13 (1941–44), a Nazi extermination operation that killed prisoners who were sick, elderly, or deemed no longer fit for work

- Aktion Erntefest (November 1943), an operation to murder all the remaining Jews in the Lublin Ghetto

- August Frank memorandum theft of victim's property

- Operation Reinhard in Warsaw (Grossaktion Warsaw, July 1942), a similar operation to move Jews to the death camps

- Katzmann Report (1943), a document detailing the outcome of Operation Reinhard in southern Poland.

- Korherr Report, a report from the SS statistical bureau detailing how many Jews remained alive in Nazi Germany and occupied Europe in 1943

- Operation Reinhard in Kraków (June 1942), the clearance of the Jewish ghetto

Footnotes

- ^ The Treblinka and Sobibor death camps were built in roughly the same timeframe. During the construction of the gas chambers at Sobibor SS-Scharführer Erich Fuchs installed a 200-horsepower, water-cooled V-8 gasoline engine as the killing mechanism there, according to his own postwar testimony at the Sobibor trial.[24] Fuchs installed a similar engine at Treblinka as well. There's an ongoing debate with regard to the type of fuel at Treblinka used as the lethal agent.[25] The chief argument for its identification as petrol (i.e., gasoline, or gas) comes directly from the eyewitness testimonies of insurgents who survived the Treblinka uprising. On 2 August 1943, they set ablaze a petrol tank causing it to explode. No second tank containing a different type of fuel (i.e., diesel) was ever mentioned in any known literature on the subject. All diesel motors require diesel fuel; the engine and the fuel work together as a system. An effort in the late '30s to extend the diesel engine's use to passenger cars was interrupted by World War II.[26] Therefore, the cars driven by the SS at Trebinka (see Rajzman 1945 at U.S. Congress, and Ząbecki's court testimonies at Düsseldorf) could not have been fueled by diesel, and neither was the killing apparatus without a second fuel tank on premises.[27][28]

Citations

- ^ IPN (1942). "From archives of the Jewish deportations to extermination camps" (PDF). Karty. Institute of National Remembrance, Warsaw: 32. Document size 4.7 MB. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ a b Stone, Lewi (2019). "Quantifying the Holocaust: Hyperintense kill rates during the Nazi genocide". Science Advances. 5 (1): eaau7292. Bibcode:2019SciA....5.7292S. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aau7292. PMC 6314819. PMID 30613773.

- ^ a b c Yad Vashem (2013). "Aktion Reinhard" (PDF). Shoah Resource Center, The International School for Holocaust Studies. Document size 33.1 KB. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ^ Gerlach, Christian (2016). The Extermination of the European Jews. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0521706896.

- ^ Stone, Dan (2023). The Holocaust: An Unfinished History (1st ed.). Pelican Books. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-241-38871-6.

- ^ "Operation Reinhardt (Einsatz Reinhard)". USHMM. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- ^ Grossman, Vasily (1946). "The Treblinka Hell" (PDF). The Years of War (1941–1945) (PDF). Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House. pp. 371–408. Document size 2.14 MB. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-10-06 – via Internet Archive.

——. "The Hell of Treblinka". The Road: Stories, Journalism, and Essays. V. Grossman, R. Chandler, E. Chandler, O. Mukovnikova (trans.). Retrieved 1 August 2015.[permanent dead link]

—— (19 September 2002) [1958]. Треблинский ад [Treblinka Hell] (in Russian). Воениздат. - ^ Sereny, Gitta (2001). The Healing Wound: Experiences and Reflections on Germany 1938–1941. Norton. pp. 135–46. ISBN 978-0-393-04428-7.

- ^ Kaye, Ephraim (1997). Desecraters of Memory. pp. 45–46. Archived from the original on 2017-11-15.

- ^ Hilberg, Raul (2003). The Destruction of the European Jews (3rd ed.). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. pp. 1033, 1036–1037. ISBN 9780300095579.

Killing centers could be hidden, but the disappearance of major communities was noticed in Brussels and Vienna, Warsaw and Budapest.

- ^ Browning, Christopher (2005). The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939 – March 1942. Arrow. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-8032-5979-9.

First 'provisional gas chamber' was constructed at Fort VII in Poznań (occupied Poland), where the bottled carbon monoxide was tested by Dr. August Becker already in October 1939.

- ^ Sereny, Gitta (2013) [1974, 1995]. Into That Darkness: From Mercy Killing to Mass Murder. Random House. pp. 54–. ISBN 978-1-4464-4967-7. Retrieved 5 October 2014 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b ARC (17 October 2005). "The Origin of the Expression 'Aktion Reinhard'". Aktion Reinhard Camps. Retrieved 5 August 2015. Sources: Arad, Browning, Weiss.

- ^ Burian, Michal; Aleš (2002). "Assassination — Operation Arthropoid, 1941–1942" (PDF). Ministry of Defence of the Czech Republic. Retrieved 5 October 2014. Document size 7.89 MB.

- ^ a b History of the Belzec extermination camp [Historia Niemieckiego Obozu Zagłady w Bełżcu] (in Polish), Muzeum – Miejsce Pamięci w Bełżcu (National Bełżec Museum & Monument of Martyrdom), October 2015, archived from the original on 2015-10-29 – via Internet Archive

- ^ a b Friedländer, Saul (2007). The Years of Extermination: Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1939–1945. HarperCollins. pp. 346–347. ISBN 978-0-06-019043-9.

- ^ Beevor, Antony (2012). The Second World War. Little, Brown. p. 584. ISBN 978-0-316-08407-9. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Browning, Christopher R. (1998) [1992]. "Arrival in Poland". Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland (PDF). Penguin Books. pp. 52, 77, 79, 80. Document size 7.91 MB complete. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-10-19. Retrieved 2014-10-05.Also:

- ^ Black, Peter R. (2006). "Police Auxiliaries for Operation Reinhard". In David Bankier (ed.). Secret Intelligence and the Holocaust. Enigma Books. pp. 331–348. ISBN 1-929631-60-X – via Google Books.

- ^ Kudryashov, Sergei (2004). "Ordinary Collaborators: The Case of the Travniki Guards". Russia War, Peace and Diplomacy Essays in Honour of John Erickson. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson: 226–239.

- ^ a b McVay, Kenneth (1984). "The Construction of the Treblinka Extermination Camp". Yad Vashem Studies, XVI. Jewish Virtual Library.org. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ National Archives (2014), Aerial Photos, Washington, D.C. Made available at the Mapping Treblinka webpage by ARC.

- ^ Smith 2010: excerpt.

- ^ Arad, Yitzhak (1987). Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka. The Operation Reinhard Death Camps. Bloomington, Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. p. 31. ISBN 0-253-21305-3 – via Google Books.

Testimony of SS Scharführer Erich Fuchs in the Sobibór-Bolender trial, Düsseldorf (quote). 2.4.1963, BAL162/208 AR-Z 251/59, Bd. 9, 1784.

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - ^ Harrison, Jonathan; Muehlenkamp, Roberto; Myers, Jason; Romanov, Sergey; Terry, Nicholas (December 2011). "The Gassing Engine: Diesel or Gasoline?". Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka. Holocaust Denial and Operation Reinhard. A Critique... Holocaust Controversies, White Paper, First Edition. pp. 316–320.

Protokol doprosa, Nikolay Shalayev, 18.12.1950, in the Soviet criminal case against Fedorenko, vol. 15, p. 164. Exhibit GX-125 in US v. Reimer.

- ^ "Diesel Fuels Technical Review" (PDF). Chevron. 2007. pp. 1–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-07-12. Retrieved 2017-11-12.

- ^ Kopówka & Rytel-Andrianik 2011, p. 110.

- ^ Chris Webb & C.L. (2007). "The Perpetrators Speak". Belzec, Sobibor & Treblinka Death Camps. Holocaust Research Project.org. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ Ruckerl, Adalbert (1972). NS-Prozesse. C. F. Muller. pp. 35–42.

- ^ Piotr Ząbecki; Franciszek Ząbecki (12 December 2013). "Był skromnym człowiekiem" [He was a humble man]. Życie Siedleckie. p. 21. Treblinka trials, Düsseldorf. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013.

- ^ Yad Vashem (2013). "Chelmno" (PDF). Holocaust. Shoah Resource Center. Document size 23.9 KB. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ^ Browning, Christopher R. (2011). Remembering Survival: Inside a Nazi Slave-Labor Camp. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-0393338874.

- ^ The German Kulmhof Death Camp in Chełmno on the Ner, 1941–1945, Chełmno Muzeum of Martyrdom, Poland, archived from the original on March 9, 2014 – via Internet Archive

- ^ Ghettos, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- ^ Golden, Juliet (January–February 2003). "Remembering Chelmno". Archaeology. 56 (1). Archaeological Institute of America: 50.

- ^ Arad 1999, p. 37.

- ^ Radlmaier, Steffen (2001). Der Nürnberger Lernprozess: von Kriegsverbrechern und Starreportern. Eichborn. p. 278. ISBN 978-3-8218-4725-2.

- ^ Kopówka & Rytel-Andrianik 2011, pp. 44, 74.

- ^ The Holocaust Encyclopedia. "Belzec". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on January 7, 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2015 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Kopówka & Rytel-Andrianik 2011, pp. 78–79.

- ^ United States Department of Justice (1994), From the Record of Interrogation of the Defendant Pavel Vladimirovich Leleko, Court of Appeals, Sixth Circuit, Appendix 3: 144/179, archived from the original on 16 May 2010, retrieved 5 August 2016 – via Internet Archive Original: the Fourth Department of the SMERSH Directorate of Counterintelligence of the 2nd Belorussian Front, USSR (1978). Acquired by OSI in 1994

- ^ Arad, Yitzhak (1999). Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps. Indiana University Press. pp. 152–153. ISBN 978-0-253-21305-1.

- ^ Browning, Christopher R.; Mattäus, Jürgen (2007). The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939 – March 1942. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 191–192. ISBN 978-0-8032-5979-9. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ Israel Gutman (1994). Resistance. Houghton Mifflin. p. 200. ISBN 0395901308.

- ^ Gordon Williamson (2004). The SS: Hitler's Instrument of Terror. Zenith Imprint. p. 101. ISBN 0-7603-1933-2.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Edelman, Marek. "The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising". Interpress Publishers (undated). pp. 17–39. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ Browning 1998, p. 116.

- ^ Kurt Gerstein (4 May 1945). "Gerstein Report, in English translation". DeathCamps.org. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

On 18 August 1942, Waffen-SS officer Kurt Gerstein had witnessed at Belzec the arrival of 45 wagons with 6,700 people of whom 1,450 were already dead on arrival. The train came with the Jews of the Lwów Ghetto, less than a hundred kilometres away

- ^ Arad 1999, p.76.

- ^ Shirer 1981, p. 969, Affidavit (Hoess, Nuremberg).

- ^ Chris Webb & Carmelo Lisciotto (2009). "The Gas Chambers at Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka". Descriptions and Eyewitness Testimony. Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ Webb, Chris; C.L. (2007). "Belzec, Sobibor & Treblinka Death Camps. The Perpetrators Speak". HEART. Archived from the original on September 6, 2011. Retrieved 14 October 2014 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Webb, Chris; Carmelo Lisciotto (2009). "The Gas Chambers at Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka. Descriptions and Eyewitness Testimony". H.E.A.R.T. Archived from the original on February 22, 2010. Retrieved 14 October 2014 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Adams, David (2012). "Hershl Sperling. Personal Testimony". H.E.A.R.T. Archived from the original on December 20, 2012 – via Internet Archive. The Lazarett was surrounded by a tall barbed-wire fence, camouflaged with brushwood to screen it from view. Behind the fence was a big ditch which served as a mass grave, with a constantly burning fire.

- ^ Kopówka & Rytel-Andrianik 2011, p. 84.

- ^ Carol Rittner, Roth, K. (2004). Pope Pius XII and the Holocaust. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-8264-7566-4.

- ^ Public Record Office, Kew, England, HW 16/23, decode GPDD 355a distributed on January 15, 1943, radio telegrams nos 12 and 13/15, transmitted on January 11, 1943.

- ^ Hanyok, Robert J. (2004), Eavesdropping on Hell: Historical Guide to Western Communications Intelligence and the Holocaust, 1939–1945 (PDF), Center for Cryptographic History, National Security Agency, p. 124

- ^ Between March and December 1942, the Germans deported some 434,500 Jews, and an indeterminate number of Poles and Roma (Gypsies) to Belzec, to be killed. Bełżec extermination camp

- ^ In all, the Germans and their auxiliaries killed at least 167,000 people at Sobibór. Sobibor extermination camp

- ^ The Höfle Telegram indicates some 700,000 killed by 31 December 1942, yet the camp functioned until 1943; hence, the true death toll likely is greater. Reinhard: Treblinka Deportations Archived 2013-09-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Abstract: Peter Witte and Stephen Tyas, "A New Document on the Deportation and Murder of Jews during 'Einsatz Reinhardt' 1942." (Internet Archive) Holocaust and Genocide Studies 15:3 (2001) pp. 468–486.

- ^ "KL Majdanek: Kalendarium". Państwowe Muzeum na Majdanku. Archived from the original on 2011-02-13. Retrieved 2015-05-23.

- ^ Reszka, Paweł P. (23 December 2005). "Majdanek Victims Enumerated. Changes in the history textbooks?". Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum.

Two figures of the number of Majdanek victims have usually been in use—360,000 or 235,000. Kranz, director of the Research Department of the State Museum at Majdanek, asserts that approximately 59,000 Jews and 19,000 people of other ethnic backgrounds, mostly Poles and Byelorussians, died there. Kranz published his estimate in the latest edition of the journal Zeszyty Majdanka. ... However, we do not know the definitive number of prisoners who passed through the camp or the number of those whose deaths the camp administration did not register. It cannot be ruled out that new documents will come to light that alter Kranz's findings.

- ^ Saul Friedländer (February 2009). Nazi Germany And The Jews, 1933–1945 (PDF). HarperCollins Publishers. pp. 293–294 / 507. ISBN 978-0-06-177730-1. Complete. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ^ a b c Browning, Christopher (2000). Nazi Policy, Jewish Workers, German Killers. Cambridge University Press. p. 71. ISBN 0-521-77490-X.

- ^ Lisciotto, Carmelo (2007). "The Reichsbank". H.E.A.R.T. Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ KL Lublin Museum (13 September 2013). "Trials of war criminals 1946–1948" [Procesy zbrodniarzy]. Wykaz sądzonych członków załogi KL Lublin/Majdanek (Majdanek SS staff put on trial). Lublin. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ "SS-Hauptscharfuehrer Konrad Morgen – the Bloodhound Judge". 9 August 2001. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ Snyder, Louis Leo (1998). Encyclopedia of the Third Reich. Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 978-1-85326-684-3.

- ^ Arad, Yitzhak (1984), "Operation Reinhard: Extermination Camps of Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka" (PDF), Yad Vashem Studies XVI, 205–239 (26/30 of current document), archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-18 – via Internet Archive,

The Attempt to Remove Traces.

- ^ Wiernik, Jankiel (1945), "A year in Treblinka", Verbatim translation from Yiddish, American Representation of the General Jewish Workers' Union of Poland, retrieved 30 August 2015 – via Zchor.org, digitized into fourteen chapters,

The first ever published eye-witness report by an escaped prisoner of the camp.

- ^ Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team (2007). "Ernst Lerch". Holocaust Research Project.org. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

References

- Arad, Yitzhak (1999) [1987]. Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-21305-3. ASIN 0253213053 – via Google Books.

- Kopówka, Edward; Rytel-Andrianik, Paweł (2011), "Treblinka II – Obóz zagłady" [Treblinka II – Death Camp monograph] (PDF), Dam im imię na wieki [I will give them an everlasting name. Isaiah 56:5] (in Polish), Drohiczyńskie Towarzystwo Naukowe [The Drohiczyn Scientific Society], p. 110, ISBN 978-83-7257-496-1, archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2014, retrieved 4 August 2015 – via Internet Archivedocument size 20.2 MB. Monograph, chapt. 3: with list of Catholic rescuers of Jews who escaped from Treblinka; selected testimonies, bibliography, alphabetical indexes, photographs, English language summaries, and forewords by Holocaust scholars.

- Shirer, William L. (1981), The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany (internal link), Simon and Schuster, ISBN 0-671-62420-2, also at Amazon: Search inside

- Smith, Mark S. (2010). Treblinka Survivor: The Life and Death of Hershl Sperling. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5618-8. Retrieved 12 November 2013 – via Google Books. See Smith's book excerpts at: Hershl Sperling: Personal Testimony by David Adams.