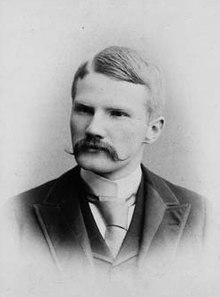

Charles Homer Haskins

Charles Homer Haskins (December 21, 1870 – May 14, 1937) was an American medievalist at Harvard University.[1] He was an advisor to U.S. President Woodrow Wilson. He is widely recognized as the first academic medieval historian in the United States, and the Haskins Medal was named in his honor.

Biography

[edit]Haskins was born in Meadville, Pennsylvania.[2]

He was a prodigy, fluent in both Latin and Greek while still a young boy, taught by his father.[2] He graduated from Johns Hopkins University at the age of 16, and then studied in Paris and Berlin.[1][2] He received a Ph.D. in history from Johns Hopkins University and began teaching there before the age of 20.[2] In 1890, he was appointed instructor at the University of Wisconsin, became a full professor in two years, and from 1892 to 1902 held the European history chair there.[3] In 1902 he moved to Harvard University, where he taught until 1931.[3]

Haskins became politically involved enough to become a close advisor of U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, whom he had met at Johns Hopkins. When Wilson attended the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 where the Treaty of Versailles was drawn up, he brought only three advisors including Haskins, who served as chief of the Western European division of the American commission.

Haskins was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1913 and the American Philosophical Society in 1921.[4][5]

He died on May 14, 1937, in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[1] His widow died in 1970.[6]

Legacy

[edit]He was primarily a historian of institutions, like medieval universities and governments. His works reflect the mostly twentieth-century optimistic, liberal view that progressive government by "the best and brightest" is the way to go. His histories of medieval Europe's institutions stress the efficiency and successes of their governing bureaucracies, implicitly analogous to those of modern nation states.

Haskins's most well known pupil was medieval historian Joseph Strayer, who went on to teach many American medievalists of the next generation(s) at Princeton University, some still active today. Other eminent medievalists trained by Haskins included Lynn White, Jr. (UCLA), Gaines Post (Wisconsin and Princeton), Carl Stephenson (Cornell), Edgar B. Graves (Hamilton College), and John R. Williams (Dartmouth).

The Haskins Society, named in his honor was organized in 1982, a "Founding Father" being the late C. Warren Hollister.[7] It publishes an annual Journal whose volume 11 (2003) reconsidered Haskins' magnum opus seventy years after its publication.[8] From 1920 to 1926, he was also the first chairman of the American Council of Learned Societies, which still offers a distinguished lecture series named after him.

His son George Haskins was a University of Pennsylvania Law School professor.

The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century

[edit]Haskins' most famous work is The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century (1927). The word "Renaissance," even to historians in the early 20th century, meant the 15th-century Italian Renaissance, as defined by 19th-century Swiss historian Jakob Burckhardt in his The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy. Haskins opened a broader view when he asserted, "The continuity of history rejects violent contrasts between successive periods, and modern research shows the Middle Ages less dark and less static, the Renaissance less bright and less sudden, than was once supposed. The Italian Renaissance was preceded by similar, if less wide-reaching, movements."

Haskins' fresh assessment of a sort of pre-renaissance, ushering in the High Middle Ages around 1070, was resisted by some scholars at first. His approach was broader than a mere literary revival: he stated in his preface that he found that 12th-century Europe

was in many respects an age of fresh and vigorous life. The epoch of the Crusades, of the rise of towns, and of the earliest bureaucratic states of the West, saw the culmination of Romanesque art and the beginnings of Gothic art; the emergence of vernacular literatures; the revival of the Latin classics and of Latin poetry and Roman law; the recovery of Greek science, with its Arabic additions, and of much of Greek philosophy; and the origin of the first European universities. The twelfth century left its signature on higher education, on scholastic philosophy, on European systems of law, on architecture and sculpture, on the liturgical drama, on Latin and vernacular poetry. ... We shall confine ourselves to the Latin side of this renaissance, the revival of learning in the broadest sense—the Latin classics and their influence, the new jurisprudence and the more varied historiography, the new knowledge of the Greeks and Arabs and its effects upon western science and philosophy.

Haskins focused on high culture to prove that the 12th century was indeed a period of dynamic growth. He looked at the history of art and science, the universities, philosophy, architecture and literature, and provided a celebratory view of the period. More recent views of the renewal have expanded the focus.[9] Once the ice had been broken, other scholars concentrated on an earlier, more constrained revival of learning in some circles under the patronage of Charlemagne, and began talking and thinking of a "Carolingian Renaissance" of the ninth century. By 1960, Erwin Panofsky could write of Renaissance and Renascences in Western Art.

Less wide-ranging was Haskins' earlier study of the Normans, Norman Institutions (1918), which still forms the basis of current scholarly understanding of how medieval Normandy functioned. He also wrote the more popular book The Normans in European History (1915).

Works

[edit]- The Yazoo Land Companies. New York: The Knickerbocker Press, 1891.

- A History of Higher Education in Pennsylvania. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1902 (with William I. Hull).

- The Normans in European History. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin Company, 1915.

- Norman Institutions. Harvard University Press, 1918.

- Some Problems of the Peace Conference. Harvard University Press, 1920 (with Robert Howard Lord).

- The Rise of Universities. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1923.

- Studies in the History of Mediæval Science. Harvard University Press, 1924.

- The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century. Harvard University Press, 1927.

- Studies in Mediaeval Culture. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., 1958 (1st Pub. 1929).

Selected articles

[edit]- "The Vatican Archives," The American Historical Review, Vol. 2, No. 1, 1896.

- "The Life of Medieval Students as Illustrated by their Letters," The American Historical Review, Vol. 3, No. 2, 1898.

- "Opportunities for American Students of History at Paris," The American Historical Review, Vol. 3, No. 3, 1898.

- "Robert Le Bougre and the Beginnings of the Inquisition in Northern France," Part II, The American Historical Review, Vol. 7, No. 3/4, 1902.

- "The Early Norman Jury," The American Historical Review, Vol. 8, No. 4, 1903.

- "The University of Paris in the Sermons of the Thirteenth Century," The American Historical Review, Vol. 10, No. 1, 1904.

- "The Sources for the History of the Papal Penitentiary," The American Journal of Theology, Vol. 9, No. 3, 1905.

- "Normandy Under William The Conqueror," The American Historical Review, Vol. 14, No. 3, 1909.

- "A List of Text-Books from the Close of the Twelfth Century," Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, Vol. 20, 1909.

- "The Sicilian Translators of the Twelfth Century and the First Latin Version of Ptolemy's Almagest," Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, Vol. 21, 1910.

- "A Canterbury Monk at Constantinople, c. 1090," The English Historical Magazine, Vol. 25, 1910.

- "Adelard of Bath," The English Historical Review, Vol. 26, 1911.

- "England and Sicily in the Twelfth Century," Part II, The English Historical Review, Vol. 26, 1911.

- "The Inquest of 1171 in the Avranchin," The English Historical Review, Vol. 26, 1911.

- "Further Notes on Sicilian Translations of the Twelfth Century," Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, Vol. 23, 1912.

- "The Government of Normandy Under Henry II," The American Historical Review, Vol. 20, No. 1, 1914.

- "Mediaeval Versions of the Posterior Analytics," Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, Vol. 25, 1914.

- "The Government of Normandy Under Henry II," The American Historical Review, Vol. 20, No. 2, 1915.

- "The Reception of Arabic Science in England," The English Historical Review, Vol. 30, 1915.

- "Charles Gross: From the Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society for December, 1915," Boston, 1916.

- "The Materials for the History of Robert I of Normandy," The English Historical Review, Vol. 31, 1916.

- "A Charter of Canute for Fécamp," The English Historical Review, Vol. 33, 1918.

- "Leo Tuscus," The English Historical Review, Vol. 33, 1918.

- "The Greek Element in the Renaissance of the Twelfth Century," The American Historical Review, Vol. 25, No. 4, 1920.

- "The 'De Arte Venandi Cum Avibus' of the Emperor Frederick II," The English Historical Review, Vol. 36, 1921.

- "Science at the Court of the Emperor Frederick II," The American Historical Review, Vol. 27, No. 4, 1922.

- "The Saar Territory as It Is Today," Foreign Affairs, Vol. 1, No. 2, 1922.

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c "Prof. C. H. Haskins, Long At Harvard. History Professor Emeritus And Internationally Known Scholar Dies At 67. Active In Peace Efforts Served U.S. commissions Abroad. Honored By European Nations And Many Universities. Johns Hopkins Graduate At 17". The New York Times. May 15, 1937.

- ^ a b c d Charles Homer Haskins The rise of universities, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1923, 1957, p. v.

- ^ a b F. M. Powicke, "Charles Homer Haskins", The English Historical Review, vol. 52, no. 208 (Oct. 1937), p. 649.

- ^ "Charles Homer Haskins". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. February 9, 2023. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ "Mrs. Charles Haskins, 91, Widow of Harvard Dean". The New York Times. June 2, 1970.

- ^ "More About Us". The Haskins Society. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^ "JournalContents" (PDF). Haskins Society Journal. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 15, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^ Robert L. Benson and Giles Constable, eds., Renaissance and Renewal in the Twelfth Century

External links

[edit]- Works by or about Charles Homer Haskins at the Internet Archive

- Works by Charles Homer Haskins at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- "Charles Homer Haskins". In Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- A brief analysis of Haskins, Renaissance of the Twelfth Century

- Haskins Society webpage

- ACLS Charles Homer Haskins lecture series Archived September 21, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- Norman Institutions (1918) Archived August 10, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

'

- 1870 births

- 1937 deaths

- American medievalists

- Presidents of the American Historical Association

- Fellows of the Medieval Academy of America

- Harvard University Department of History faculty

- Johns Hopkins University alumni

- Johns Hopkins University faculty

- People from Meadville, Pennsylvania

- University of Wisconsin–Madison faculty

- Corresponding fellows of the British Academy

- Members of the American Philosophical Society